Watery Terror: Ivan Aivazovsky and the Marine Sublime

A great master of Romantic painting captured the terror and beauty of the sea in a distinctive way.

Armenian painter Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900) was a painter of marines (seascapes). As often happened with nationalities incorporated into the Russian Empire, he was frequently referred to as “Russian”. He travelled widely, especially in the Empire, making records of the sights and phenomena. He was hugely prolific, producing 6,000 paintings and immensely popular, his fame spread across Europe via exhibitions (one-man and group) and reproduction prints. In 1842 J.M.W. Turner wrote a poem extolling Aivazovsky’s skill, preceding even the Armenian’s 1843 London exhibition.

Although today his star has faded throughout the rest of Europe, he is still highly esteemed in Armenia, Russia and Ukraine, not wholly due to patriotic pride. A museum of his paintings in his native town, Feodosia, Armenia, where he is still regarded as one of the great sons of Armenia. Aivazovsky is a key figure in any survey of Romanticism and Russian painting, as the artist lived in St Petersburg for a time and lived his life as a Russian subject, although he developed ideas and responded to colleagues in Europe. He also might be seen as a latter-day exponent of the Claudian seascape and a counterpart to the Hudson River School in North America.

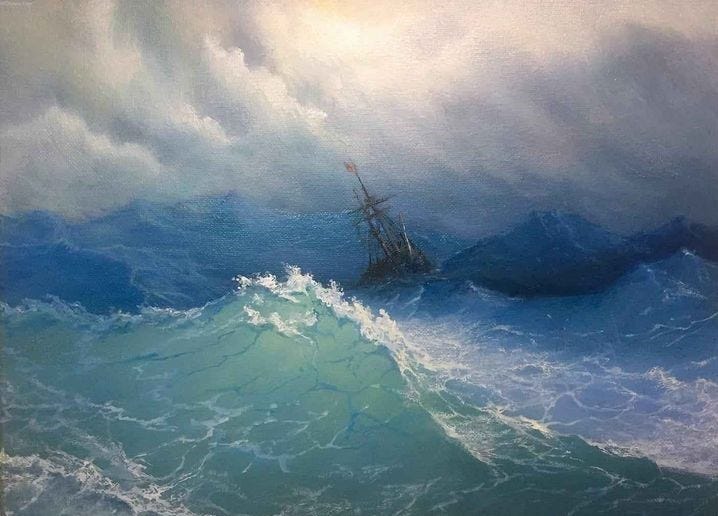

His main topics were views of the sea, but he also painted Orientalist scenes (mainly of the Ottoman Empire, which occupied part of Armenia), landscapes, Biblical scenes, History paintings and portraits. His marines are very varied. The locale is Mediterranean to polar; weather can be anything between placid and tempestuous; ships, boats, icebergs, lighthouses, quays and flotsam add human scale to the scenes. He had a taste for moonlit views, with broken clouds to drama to the skies. As Aivazovsky often concentrated on a dramatic incident rather than a topographical description of a coast as seen from the sea, he tended to use 3:4 formats rather than the narrower panoramic formats, unlike many marine painters.

Aivazovsky’s most remarkable works were his storm views, most including ships. As well as catching effects such as waves, scurf and spray, the paintings have the effect (or motif) of waves pierced by sunlight. This can be considered the most distinctive feature of Aivazovsky’s marine painting. Although we find such an effect in marine paintings by earlier masters, Aivazovsky perfected it. He also depicted sunlight and moonlight passing through calm water, sometimes accentuated by placing a floating object such as a lifeboat, whaling boat or barrel in the area. The sight of sunlight through waves is a sign of rough weather, something that would have sent a jolt of fear through the observer. In an age of wooden-hull vessels and steam power, high waves meant danger to anyone within sight, unless they were ashore. One did not have to imagine the peril; the artist painted many scenes of ships wrecked out at sea and upon coastal rocks. It is said that on one of his many journeys, the artist was on a ship that experienced a terrible storm that led to it being reported sunk. The artist had an excellent visual memory and reported recorded his memories in subsequent paintings.

The paintings of sunlight pierced waves are sublime imagery, commonly found in Romantic painting of the late Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. What is the sublime? The sublime in oratory was defined by Longinus as “[…] the Sublime, wherever it occurs, consists in a certain loftiness and excellence of language, and that it is by this, and this only, that the greatest poets and prose-writers have gained eminence, and won themselves a lasting place in the Temple of Fame. A lofty passage does not convince the reason of the reader, but takes him out of himself. That which is admirable ever confounds our judgment, and eclipses that which is merely reasonable or agreeable. To believe or not is usually in our own power; but the Sublime, acting with an imperious and irresistible force, sways every reader whether he will or no. Skill in invention, lucid arrangement and disposition of facts, are appreciated not by one passage, or by two, but gradually manifest themselves in the general structure of a work; but a sublime thought, if happily timed, illumines an entire subject with the vividness of a lightning-flash, and exhibits the whole power of the orator in a moment of time.”[i]

Later, the idea of the sublime being an experience that transcended reason and rational appreciation became important in Eighteenth Century discourse on visual art. Edmund Burke defines the sublime as “whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime.”[ii]

By the time of Aivazovsky, painters and writers attached to ideas of Romanticism had embraced the fearsome spectacle as a means of transporting the viewer beyond rationality and freeing him from the pretence that he was a being of logic. Art would use the physiological response to fear, beauty and the infinite to open new areas of feeling and comprehension within modern man, contradicting the Enlightenment humanism that asserted men were creatures of cognition and cogitation. Aivazovsky’s tempests were demonstrations of the overwhelming, unmasterable phenomena of nature, just like the erupting Vesuvius volcano of Wright of Derby, the waterfalls of Salvator Rosa and George Stubbs’s paintings of a lion attacking a horse. Extremity and abnormality exposed man to the sublime of the infinite or dangerous.

Immanuel Kant described the power of the dynamical sublime. “[…] Bold, overhanging, and, as it were, threatening rocks, thunderclouds piled up the vault of heaven, borne along with flashes and peals, volcanos in all their violence of destruction, hurricanes leaving desolation in their track, the boundless ocean rising with rebellious force, the high waterfall of some mighty river, and the like, make our power of resistance of trifling moment in comparison with their might. But, provided our own position is secure, their aspect is all the more attractive for its fearfulness; and we readily call these objects sublime.”1

As Kant notes, we observers of nature or art (when we are at a distance) are safe. It is frisson between the appearance of danger and the actuality of safety that produces the unique effect of an encounter with the sublime – through nature or art.

Aivazovsky was apparently not an intellectual man. Anton Chekov visited him and described him like so: “He’s not very bright, but he is a complex personality, worthy of a further study. In him alone there are combined a general, a bishop, an artist, an Armenian, an naive old peasant, and an Othello.” We can conclude that the artist was sensitive to the power of sunlight-pierced wave, without necessarily understanding why it formed such a deep impression on himself and his audience. Nor did he need to know. Following one’s instincts as an artist almost always trump the value of intellect. In old age, the artist increasingly turned to the large immersive size and depicted evermore violent scenes, heightening the experience of sublime fear in his viewers.

In the case of Aivazovsky, his genius was to notice, remember and record the sublime, not to explain it, for the sublime admits no explanation – it “confounds our judgment”. For us to appreciate the brilliance of this master it alone suffices to look and open ourselves up to the wonder of nature and the perspicacity and skill of the genius Ivan Aivazovsky.

Images and information on Aivazovsky: https://wooarts.com/ivan-aivazovsky-gallery/

[i] Longinus, On the Sublime, book I

[ii] Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Sublime and Beautiful, 1757/1759

Immanuel Kant, James Creed Meredith (trans.), Critique of Judgement, 1790, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1952

I love that first painting, the light going through that wave in the foreground and the contrasting blue in the further back waves... stunning. Aivazovsky was immensely talented, thank you for this post sharing about him and his art!

Thanks so much for this lovely piece on Aivazovsky. The paintings are stunning. It really is all about the light and the contrast. It’s heartening to see that Aivazovsky is held in such high regard in Ukraine, Russia and Armenia.