Whistler: The Barbed Butterfly

In November 1878 one of the defining events of Modernism and aesthetics took place. A libel case was brought to court in London. The plaintiff was the flamboyant and notorious London-based American painter-printmaker and the defendant (who did not appear to testify) was a famous art critic.

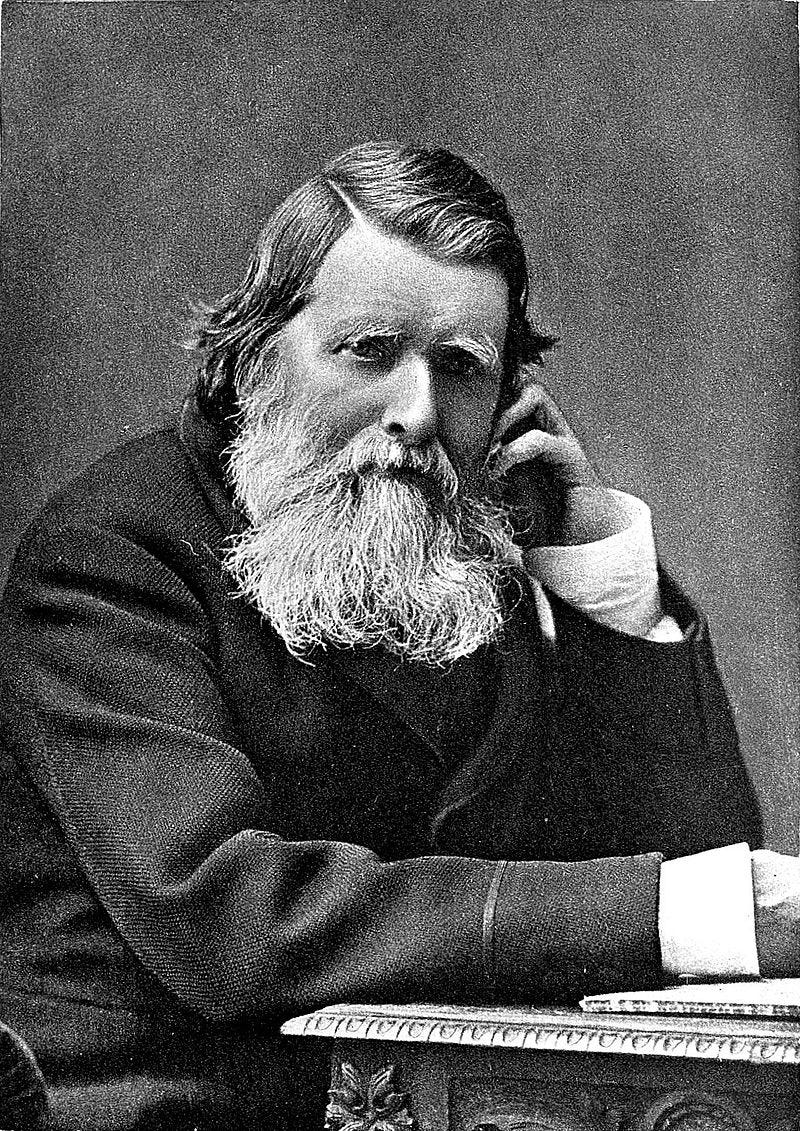

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) was the leading painter of the Aesthetic Movement. He was witty and erudite and made a point of provoking audiences with his statements on taste. He is (understandably) often assessed in relation to Wilde, whom he knew. There was a degree of competition between the pair. The young Wilde attended events Whistler spoke at and it was commonly thought that many of Wilde’s beliefs on aesthetics and art came from Whistler. Famously, Whistler and Wilde were at a gathering together and Whistler uttered a witticism. Wilde exclaimed, “I wish I had said that,” to which, Whistler replied, “You will, Oscar, you will.” Wilde addressed the painter as “Butterfly”, a symbol of ornate beauty and delicacy. Later, the pair became estranged, their egos rather than their outlooks conflicting. Not least, Whistler was a skilled writer, well known for his elegantly barbed letters to the press. Wilde may have felt, as a mere writer and no more, that the multi-talented Whistler was intimidatingly skilled and sophisticated.

Whistler was not only a painter and printmaker, but a decorator, whose ornate and exquisitely crafted Peacock Room (1877), which was a fusion of Art Nouveau and Japanese art. The use of carved wood, painted panels and gilt designs applied to leather made the interior an elaborate and expensive project, one that would incorporate the patron’s existing collection of Oriental artefacts. The Peacock Room showcased many aspects of the Aesthetic Movement’s tenets. It was expensive, exclusive, non-traditional, ornamental, culturally hybrid and incorporated design, art, furnishings and applied art in what we might call something close to an art installation. Through his decorating schemes, Whistler cultivated an eye for abstract design and the dramatic flourish.

A core principle of the Aesthetic Movement was the superiority of artifice over nature, something which marks a distinct break from the ideas of John Ruskin (1819-1900), the art critic who should have been in court that November 1878. He had written, “That Nature is always right, is an assertion, artistically, as untrue, as it is one whose truth is universally taken for granted. Nature is very rarely right, to such an extent even, that it might almost be said that Nature is usually wrong: that is to say, the condition of things that shall bring about the perfection of harmony worthy a picture is rare, and not common at all.” [i]

Aestheticism (or Aesthetics) was an avant-garde cultural movement that was influential in artistic and literary circles in Great Britain, France, Germany and the Low Countries in the 1880-1914 period. Like the associated movements of Art Nouveau, Decadence, Symbolism, Jugendstil, Secession and others, Aestheticism is noted for a concentration upon increasing sophistication of production, urbanisation of the population and detachment from traditional Christianity. In practical terms, this led to creators looking for inspiration outwards (non-Western cultures, Eastern religions, primitive art) and backwards (medievalism, archaism, pre-Christian history, guilds) to revitalise a society experiencing a rise in materialism and secularism. The figure of the dandy and flaneur – lauded by writers Charles Baudelaire and Joris-Karl Huysmans – became a staple, even ideal, commentator-cum-observer of modern society precisely because he is both an outcast and voluntary exile, detached from his host society. Baudelaire demanded the modern artist not respond to the pressure of social expectations.

The elitism in Aestheticism is perfectly expressed in Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock Lecture” (1885), later translated into French by Stéphane Mallarmé. “[…] the toilers tilled, and were athirst; and the heroes returned from fresh victories, to rejoice and to feast; and all drank alike from the artists' goblets, fashioned cunningly, taking no note the while of the craftsman's pride, and understanding not his glory in his work; drinking at the cup, not from choice, not from a consciousness that it was beautiful, but because, forsooth, there was none other! And time, with more state, brought more capacity for luxury, and it became well that men should dwell in large houses, and rest upon couches, and eat at tables; whereupon the artist, with his artificers, built palaces, and filled them with furniture, beautiful in proportion and lovely to look upon. […] And the people questioned not, and had nothing to say in the matter.” [ii]

Unabashed aesthete Whistler opposed the belief that artists had a duty to improve the lives of working people. Indeed, it was pandering to the common folk which had debased art. The proper work of the artist was to serve art and make no compromises to the cost, efficiency or common taste. He was bound to clash with Ruskin’s equally lofty but very different ideals.

Ruskin: Truth in Beauty

English art critic John Ruskin played an important role in the development of aesthetics as truth in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century. Both agreed with and disputed, his ideas were at the core of art appreciation in the Anglosphere. His 39 volumes of collected works include Modern Painters (1843-1860), Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1851-3). Ruskin’s career is intimately bound up with his championing of Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851), as the supreme painter of all time.

Ruskin disdained imitation and thought that true beauty could not come from art that mimicked appearance. “I wish to point out this distinct source of pleasure clearly at once, and only to use the word “imitation” in reference to it. Whenever anything looks like what it is not, the resemblance being so great as nearly to deceive, we feel a kind of pleasurable surprise, an agreeable excitement of mind, exactly the same in its nature as that which we receive from juggling. Whenever we perceive this in something produced by art, that is to say, whenever the work is seen to resemble something which we know it is not, we receive what I call an idea of imitation.” [iii]

Imitation is necessarily in some sense a betrayal of truth, for it is an object imitating another object which it is not. “[…] a marble figure does not look like what it is not: it looks like marble, and like the form of a man, but then it is marble, and it is the form of a man. It does not look like a man, which it is not, but like the form of a man, which it is. Form is form, bona fide and actual, whether in marble or in flesh—not an imitation or resemblance of form, but real form.” [iv]

He determines his role as a critic of art: “I shall pay no regard whatsoever to what may be thought beautiful, or sublime, or imaginative. I shall look only for truth; bare, clear, downright statement of facts; showing in each particular, as far as I am able, what the truth of nature is, and then seeking for the plain expression of it, and for that alone.” [v] He sets truth up above all other considerations.

On beauty, Ruskin wrote: “[…] I wholly deny that the impressions of beauty are in any way sensual,— they are neither sensual nor intellectual, but moral […]” [vi] This connecting beauty with morality was anathema to Whistler and his circle. Although the two were in opposition, they were actually united in their belief that imitation was antithetical to art. Yet, the two were on a collision course that was determined a year before that day in court.

Tonalism: The Forgotten Art Movement

Whistler’s paintings moved ever closer to abstraction, not because he wished to paint without recognisable imagery but because he wanted to explore the possibility of bringing together art and decoration closer through the stretching of boundaries. Like many others, he was fascinated by the colour woodblock prints from Japan. He was impressed by qualities that were considered a deficit in traditional Western art: the flatness, the planar qualities, the smooth mechanical graduation of tones, the emphasis on pattern. Whistler spent a lot of time in Paris, where Impressionist artists had incorporated many elements of Japanese prints into their art. He was also conversant with a new trend that was current in France, Germany and the USA – Tonalism.

The Tonalists, a loose grouping rather than a self-identified movement, were primarily landscape painters based in New England, influenced by the nature writings of Emerson and Thoreau. Tonalism evolved from Millet and the Barbizon School but quickly found a distinct identity by rejecting anecdotal narrative, emphasising graded tone over local colour, prioritising form over detail and demonstrating a preference for nocturnes and soft edges. The attraction to flat silhouettes, blocks of colour, atmosphere and scenes set at dawn, dusk and night defied usual thinking on what was needed of landscape painting. Whistler’s paintings of the late 1870s – made by applying very dilute paint, using muted blues, greys and greens – were Tonalist is style and character, though few now today think of them in such terms.

Tonalist painting both conflicts with and complements Aesthetic Movement thought. On one hand, Tonalism is anti-traditional and rejects narrative, detail, naturalism. It opens the door to more abstract pictorial concerns and finds a successor in Symbolism, which took up its core elements. Think of the moody landscapes of Edvard Munch, the uncanny nocturnal streets of Léon Spillaert or the hazy twilight views of Fernand Khnopff. All of these come from Tonalist precepts. Pictorialism, in photography around 1900-1910, also was an extension of Tonalism. Art Nouveau’s aqueous palette is similar to Tonalism. On the other hand, Tonalism stressed creation following observation of nature, its artists tended to reject the urban scene and it rejected the linear aspects we find in Art Nouveau. It is, in some ways, a conservative aesthetic, the proponents of which sought to displace Naturalism with a more emotive atmosphere, but who were not essentially anti-nature.

Whistler, emboldened by the steps made by the Tonalists, ventured ever closer to allowing the materials of his art to displace description. He prefigured abstract painting of the following century by allowing the materials and manipulation to remain so plainly on show. In this, however, he was not too far from late-period Turner, whose scrapings, blottings and dabbings were considered positively unseemly by those with educated taste. It was, ironically, Ruskin who would champion them most vociferously even as he condemned Whistler.

Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket

Whistler exhibited a painting called Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1874) at the Grosvenor Gallery, London in 1877. This painting was reviewed by Ruskin, who wrote: “[Recent paintings have] eccentricities [that] are almost always in some degree forced; and their imperfections gratuitously, if not impertinently, indulged. For Mr Whistler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted works into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen and heard much of cockney impudence before now, but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask 200 guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” [vii] A coxcomb is a foolish conceited dandy; the painting was priced at 200 guineas (£1 and one shilling), a unit of money charged by professionals and gentlemen rather than common tradesmen.

Whistler considered this a slur on his professionalism and thus he sued Ruskin for libel. In November 1878, the case reached court, where it became a popular sensation in the press. There is a transcript of the proceedings, which sets out Whistler’s defence for his aesthetic. On the stand, Whistler testified to his artistic training, his numerous commissions, his exhibitions and prizes. Whistler explained that his titling of works emphasised the abstract qualities of the art. “It is an arrangement of line, form, and colour first; and I make use of any incident of it which shall bring about a symmetrical result.” [viii] He stated that similar paintings in the series had sold for comparable amounts. He explained that the painting in question had taken him two days to make and that it was not a description of a specific place or event. “That painting was painted not as offering the portrait of a particular place, but as an artistic impression which had been carried away.” [ix] Most famously, when questioned whether he charged 200 guineas for the labour of two days, Whistler replied, “No; it was for the knowledge gained through a lifetime.”

Ruskin’s case – although he did not appear at the trial – was that Whistler’s painting was not true and not respectful of the spectator, because it was not the work of an artist who had a commitment to aesthetics that were honest. Although, as we have seen, Ruskin was not an advocate of literal naturalism, and allowed some latitude in his definitions of truth and beauty, he felt able to exclude Whistler from his definition of artist committed to truth. As Whistler’s testimony indicates, he actually shared some of Ruskin’s beliefs about serious art – it should convey the sensation of an event rather than literally describing, permit the necessities of the materials to dictate the approach of the artist, and rely on the subject to recognise intellectually and respond emotionally to a work of art that eschewed naturalism. Viewed objectively, the art of Ruskin’s hero Turner was not dissimilar in technique or finish to Whistler’s painting, nor were the intentions of the two artists incompatible. Although the pair would have disagreed on the moral capabilities of art (Ruskin supportive, Whistler sceptical), the Ruskin-Whistler clash seems not a matter of aesthetics as of taste and personalities.

Whistler won the case but was awarded the derisory damages of one farthing (one quarter of a penny). The costs crippled him. Although he had won a legal and moral victory (certainly as viewed by the intelligentsia and artists), he had not conclusively won any aesthetic battle. This dispute shows the break between idealism of the Victorians – typified by Ruskin – and the arch-artificiality of the Aesthetes. This event was portrayed as an advanced artist suffering an assault at the hands of the old guard, attempting to diminish his standing and achievements – a case of art critics against artists – and it became seen so in following decades. Over the following century, social utility and moral didacticism made a comeback intellectually and politically.

This article draws upon part of the forthcoming course by Alexander Adams Foundations of Aesthetics: Advanced, available to purchase from

https://www.academic-agency.com/

[i] Whistler, “Ten O’Clock Lecture” (1885)

[ii] Whistler, “Ten O’Clock Lecture” (1885)

[iii] Ruskin, Modern Painters, Vol. I, p. 18

[iv] Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. I, pp. 18-9

[v] Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. I, p. 49

[vi] Ruskin, Modern Painters, 1846, vol. 2, p. 42

[vii] Daily News, 26 November 1878, in Harrison, 2001, p. 834

[viii] Op. cit. p. 835

[ix] Op. cit. p. 837