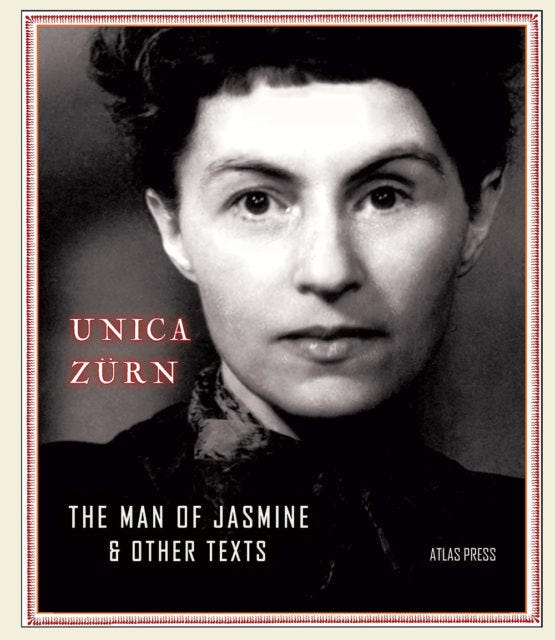

Disentangling the writing and life of German artist-author Unica Zürn (1916-1970) is both impossible and unnecessary. By inclination, I try to detach my criticism and understanding of art and literature from biography, principally because the tendency to biographise readings tends to both simplify and flatten the artistic achievement. It also expands inexorably. Having discovered a key to art – literally analogised in the phrase “roman à clef” (French, “novel with key”) – the reader starts to apply this thinking indiscriminately and universally by seeking to find actual-life sources for all of the contents of the art. This bleeds into a desire to establish the validity of the art in terms of accuracy to the life. That, of course, is not why the art was made and not how it can be best (or, perhaps, even usefully?) judged.

As Malcolm Green, translator of two books by Zürn, puts it: “Unica Zürn’s biography is inextricably interwoven with her work, and above all with the present book. Her texts are largely autobiographical or semi-autobiographical, and move between her fantasies, and later on her hallucinations, and the concrete events surrounding a series of serious mental crises, which in turn are catalysed by her writing.”[i]

Zürn was born in Grunewald, Berlin. Her happy childhood was extinguished when her parents divorced and the family house was sold and her father’s collection of exotic curios was auctioned off. She worked for UFA, the German national film studio in the 1930s and throughout the war. The collapse of the Nazi government and the exposure of atrocities in the death and concentration camps destabilised her, triggering a breakdown. Feelings of war guilt combined with latent schizophrenia – which now manifested itself in psychotic breaks, hallucinations, obsessional behaviour, episodes of disassociation and depression – which would determine the shape of her life thereafter. Divorce and separation from her children isolated her further from domesticity and routine. In the 1940s and 1950s, she wrote numerous stories and radio plays, making a modest living from writing.

In 1953 she met Hans Bellmer, whose art and writing she greatly admired, and consequently moved to Paris, where she maintained her difficult but fruitful relationship-cum-collaboration. Zürn became a model-muse for Bellmer, and subject of some erotic photographs, while Bellmer became a useful sounding board for Zürn’s ideas and writing. (The original manuscript of The Man of Jasmine omits her name and is instead ascribed to “the wife of Hans Bellmer”.) Both were difficult individuals but they did sustain each other until 1969. How the series of miscarriages that she experienced during these years affected her is uncertain.

The Man of Jasmine is a novella which was written between 1965 and 1967 and was published posthumously. Novella (subtitled “Impressions from a mental illness”) is a description that fails to convey the peculiar qualities of the writing. It is broadly narrative, describing the author’s mental crises that precipitated arrest and compulsory institutionalisation in asylums. The author flits in and out of self-awareness about how distorted her behaviour is. Numerological obsessions are recorded without any comment, as are her fixations on talismanic signs, such as the initials “HM”, symbolic to Zürn of admired author Herman Melville and poet Henri Michaux, whom she met and with whom she took hallucinogenic drugs.

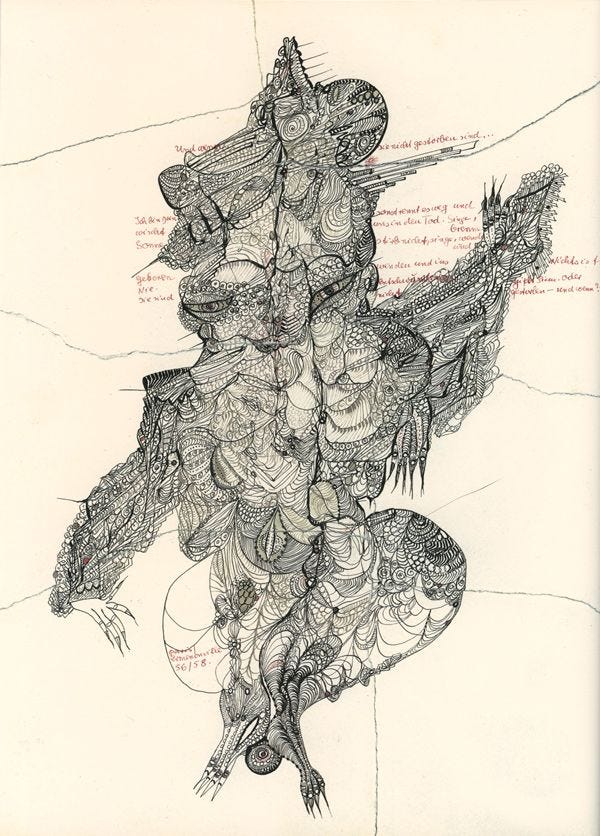

Jasmine conforms to the author’s life and describes incidents unique to her, mainly covering her post-war life in Germany and her time in a mental asylum following her arrest for failing to pay for a haircut and her inability to deal with the consequences. Some of the incidental images and stories are all the more powerful for being described so briefly. It was in institutions that Zürn started drawing. These drawings attracted first professional interest then commercial and critical interest. When attached to the Surrealists in Paris, her drawings were exhibited. She explained the obsessive repetition and expansion of her drawings like so: “[…] I couldn’t stop working on this drawing, or didn’t want to, because I experienced endless pleasure while doing it. I wanted the drawing to carry on over the edges of the paper – to infinity…”[ii] Drawings depict invented heads or fantastic animals with detailed improvised scales, feathers or patterning. Before departing Berlin, Zürn destroyed most of her drawings, something she came to regret.

“In her madness she considers it a boon to be with children who believe in the possibility of miracles, like herself.”[iii] She experiences some kinship with fellow inmates but at other times she finds them strange or exasperating. She recounts events coolly. “Tied to her bed in [restraining] suit like one crucified, she begins to cry bitterly. She has never felt such self-pity before. It is very humiliating to find yourself in a s strait-jacket. She is given the gift of an injection and she falls asleep.”[iv] In general, an absence of self-analysis gives the narrative a peculiar mixture of fantastic and banal, akin to a dream journal. And, after all, self-analysis is less interesting than simply describing things and allowing readers to take the meaning – psychological, personal, poetic – from that, as they will.

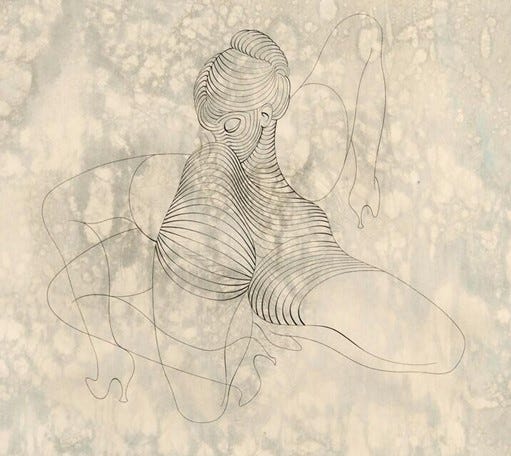

Other texts in the Atlas edition of The Man of Jasmine are short texts, including one that explicitly draws an analogy between a patient experienced sexual delirium and the creations of Bellmer. “In this posture (the moment of rapture) the woman resembles one of those astonishing cephalopods that Bellmer has often drawn: women consisting of just a head and abdomen, their arms replaced by legs. In other words, she has no arms. She even has the protruding tongue of Bellmer’s drawings of cephalopods; there is something outrageous about it.”[v]

The other stories and propositions in the volume – including one for a game of two (a man and woman only) which is for the fabrication of remarkable fantasies – display Zürn’s facility for invention, association and verbal fluency. She was noted for her elaborate anagrams, which satisfied the Surrealist practice of seeking out unexpected hidden meanings in found materials.

The House of Illnesses is an account of the author’s stay in a hospital while being treated for jaundice in 1958. It reproduces in English translation the German manuscript in facsimile, including illustrations with text. It does justice to the layout and character of the original text. In the story, the protagonist tells of her time being examined by Dr Mortimer, whose actions reveal that her carers understood that her physical malady was accompanied by a separate psychological condition. He transforms into a militaristic figure who can deliver lethal injections as a mercy. She inhabits a hospital with different zones, some delightful, others that make nauseous with their grotesque bodily associations. (Surely, a guide to the author’s aversions.) Eventually the narrator liberates herself, healing naturally. The book is lighter than her others and has more whimsy than obsession about it, though one could not dismiss it as lightweight. Some readers will no doubt draw analogies between The House of Illnesses and the writings of Leonora Carrington.

Zürn’s fate was to act out one of her fatal fantasies. After she was hospitalised and Bellmer was crippled by a stroke, she returned to spend a last night with him and then (the following morning) jump to her death from the window of the apartment. Five years later, Bellmer was laid to rest next to her. Her art and writing has been recognised more since her death, with new editions of her writings and exhibitions of her drawings bringing her to the attention of new generations. This is not just due to the wave of feminist-driven reappraisal of women artists. Zürn’s work is genuinely original and distinctive and her writings deserve these first translations into English.

Zürn spans the division between professional and outsider artists in a unique way. She was a professional writer before she commenced her more personal and fantastical stories. In the 1940s and early 1950s she wrote stories and radio-play scripts that conformed to conventional expectations; they were published and produced professionally. Yet what she produced later, sometimes under institutional confinement and subject to medication, could be regarded as outsider art. The forms that this late work takes are the repetitive flat drawing and the interior monologue. The artist was untrained and worked spontaneously; the writing often lacks a cohesive structure and is stimulated by the occurrence of associative thoughts. These are typical of the outsider producer, even if they were made by someone who had worked professionally in cinema and radio.

How much of an outsider was Zürn? She was untrained as an artist but she revised her later writings for publication and some were published in her lifetime. She exhibited and sold art; she published with the Surrealists and her partner was Bellmer, a senior Surrealist. We should not think of her as adopting a faux-naïf persona but rather working in a way that Matisse and Picasso did, internalising the example of art of children and non-Western makers to open up new avenues of expression, although in Zürn’s case it was less detached. She was attempting to access and record inner impulses in the most direct manner possible. Her writings are more effective for being as they are, rather than presented as clear delusions being described in the context of dispassionate clinical analysis conducted in retrospect. Furthermore, would such a latter approach even be feasible for someone in the grip of schizophrenia, albeit with phases of calmness? It was the mental agitation that prompted her to write and draw as she did. In that respect, her production is a map of the mind of the maker and a tool to alleviate distress. Whatever the cause, and wherever she falls in the categorisation of professional/outsider, Zürn’s art and writing is well worth becoming acquainted with.

Unica Zürn, Malcolm Green (trans., afterword), The House of Illnesses, Atlas Books, 2019, 96pp, hardback, £13.50, ISBN 978 1913407 001

Unica Zürn, Malcolm Green (trans., intro.), The Man of Jasmine & Other Texts, Atlas Books, 2020, 192pp, hardback, £17.50, ISBN 978 1 900565 820

[i] P. 7, Jasmine

[ii] P. 89, Jasmine

[iii] P. 89, Jasmine

[iv] P. 94, Jasmine

[v] P. 128, Jasmine