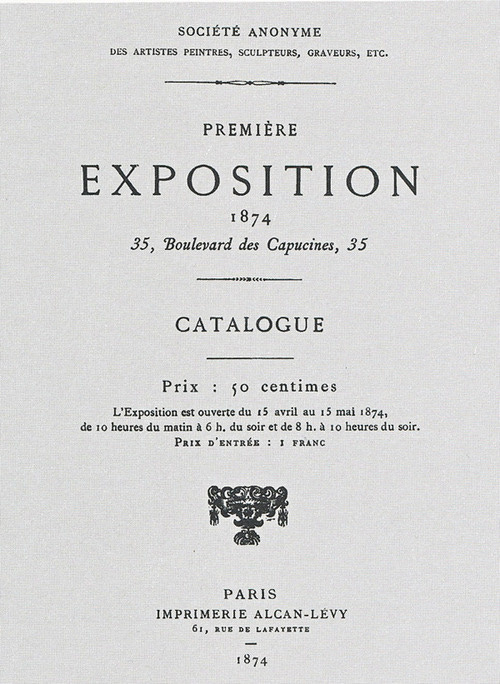

When the movement we recognise under the name “the Impressionists” first exhibited together, they called the 1874 exhibition, Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs (“Co-operative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers”), held at Nadar’s photographic studio in Paris. They gave themselves no title, agreed no core principles, signed no manifesto. They came together in common cause in rejection of the Académie and opposition to hanging jury of the annual salon, where France’s most talented professional artists exhibited, sold and were awarded prizes. Many of the exhibitors at the subsequent exhibitions had been rejected by the Académie and the salon juries, but some had not. It was Degas who insisted artists choose: henceforth they could exhibit as independents or choose the salon; they could not do both. In one respect, the motivation for the series of annual exhibitions was pragmatic or prosaic: a group of artists wanted to exhibit and sell art that official channels blocked. They wanted to advance their careers and earn money. Discrediting the state bodies was secondary; for some, perhaps it was not their intention at all, just simply an inference that others made.

When one examines the list of exhibitors at the Independent exhibitions of 1874-86, one is struck by the indisputable heterogeneity of styles, attitudes and schools. There are some artists who conventional to a T, including some sculptors of portrait busts. Some were quite established; ages spanned from the young to elderly. While all were competent, not all were original or distinguished and have lapsed into deserved obscurity. Yet, in retrospective, we separate and elevate those we call “Impressionists” because of their unfinished surfaces, rejecting the glassy varnished surfaces of the salon painters, proclivity towards the non-narrative, tendency to work plein air, painting on light grounds, committing to realism above idealism and centring petit bourgeois and working-class people as subjects for art. These shared aspects make the Impressionists stand out and retrospectively form the style of the school. The process of evolution (or at least change) was so accelerated at the time that the last exhibitions included artists such as Gauguin and Seurat who are classed as Neo-Impressionists or Post-Impressionists – the second generation of Impressionists who had developed significantly enough to be classed as successors to the exhibitions of an older generation who had started the Independent exhibitions.

What happened with the emergence of these “Impressionists” may be the case for our movement, where our style can be classed and described discretely only later, not by ourselves. It is important for us, as dissidents, to recognise that we can bond in opposition, perhaps only later coming to discern common aesthetic ideals, subjects or practices within the dissenting body. In this initial phase, it seems unwise to apply stylistic or technical criteria to those who might wish to describe themselves as part of the dissident arts movement. Yet we should retain the right to disassociate our group from any individuals or groups who claim affiliation, on the grounds that they acting contrary to intentions or good standing of our movement, with no right of appeal. A movement should be based or common benefits, experienced in shared and individual ways. Some members will gain more from collective action than others, as in true of all group activity. The group activity has meaning as an assertion of unity across one stratum, for artists who usually work and think in a solitary manner.

There are times when art is made in isolation but is seen (at a distance) to be connected. Consider the Symbolist movement. Running from the 1850s (or even the 1820s) in multiple North and Central European countries (and to a lesser extent in North America), this movement spanned continents, encompassed many distinct schools and covers artists who did not know of each other’s work, yet we see many common themes. These are two examples of movements not centred on explicit creeds. The first is the Impressionists, with artists co-located in time, place and professional cognisance of their fellows but with disparate stylistic, thematic, iconographic, political and technical concerns; the second is the Symbolists, with artists generally divided by location, time and professional cognisance of their fellows but with similar stylistic, thematic, iconographic, political and technical concerns. Both are now seen as cohesive, yet at the time the artists did not (generally) link themselves formally.

We can think of the Impressionists and Symbolists as opposites to the Italian Futurists, who had a joint manifesto and committed to explicit aesthetic positions and political goals. This also applies to a slightly lesser degree to the Surrealists in Paris, organised under André Breton. Like the Futurists, they spread ideas and set an example of what was expected from group members through publications in periodicals, as well as their own journals, and newsletters. The Surrealists, who advocated psychic liberation and pursuit of the personal subconscious, were also politically orthodox Communists and prone to endless rollcalls of the faithful in terms of joint letters. The Surrealists formed groups that would examine members in hearings to determine conformity before voting on whether to expel the member. It was the worst aspects of the clique and political splinter faction.

For a new movement in our age, the Surrealist model seems the worst of all. While it led to a degree of artistic prominence and financial success for members, many of those Surrealist artists had private collectors and commercial galleries unconnected to the movement proper. The endless wrangles about who followed orthodoxy led to separate factions, such as the Documents group, headed by Georges Bataille. It also resulted in some of the best known Surrealists – Giacometti, Dalí, Masson – being excommunicated, with some of the best and most typical work of the school (style) being made outside the movement (organisation). This clearly damaged the credibility of the movement. The contrary peril is that careerists, opportunists and bad-faith actors take up the mantle of the dissident art movement while failing to act along the movement’s main lines of artistic and political solidarity – or actually work against them. While any movement needs to possess a degree of conformity, the trials and expulsions of the Surrealist group (with endless internal drama driven by personal animus) are not feasible in an era of cancel culture. I fear that any artistic movement which relies on social media is at the mercy of drama queens, malicious individuals and tittle-tattles, seeking to use public channels of Twitter, YouTube and other social media to discredit fellow members, exclude rivals, seek popularity and spread gossip. Under such circumstances, Surrealism would have spread more widely, in terms of creators and audience, but it would have failed to maintain artistic coherence.

A protocol which might aid the dissident art movement is one that allows members to promote art and ideas through publicly visible channels but requests (and if necessary enforces) a code of silence regarding personal disagreements and individual clashes. This is difficult because artistic ideas are often deeply held by artists, in that artist and idea come to be viewed as inextricably interlinked. Generally, artists do not divorce themselves from principles or their past (or recent) work. Such breaks can be seen as admissions of failure or reversals in stance. It seems to damage the credibility of the artist and (by inference) discredit the art. So, in a movement with disagreement about artistic issues, disputes cannot help but become personal. Art history is full of such incidents and we shall be unable to avoid them. We can help by criticising ideas and art rather than artists. Bearing those qualifications in mind, what overall principles should a successful artistic movement have?

1) Generosity. As individuals who do not believe in egalitarianism – that is to say, all are not equal nor is making all equal possible or desirable – we recognise that some of us are more skilled, more original, more powerful as artists than others. We should extend to others who share our aims and beliefs and play an active part in our community (on individual terms, by advancing our cause or by dint of their artistic contribution) a degree of generosity. In other words, we allow in those who are committed and serious, overlooking their shortcomings as artists, while at the same time urging all to excel. This is the spirit of collegiality. We should not publicly disparage anyone who is supporting or contributing to the movement. We must act without malice.

2) Seriousness. We are serious about our principles, supporting our fellows, protecting our heritage, advancing our values, sustaining our viability. That seriousness should extend into all areas of our public conduct. That does not mean being sombre and grand and self-important, but taking our principles seriously. One means of doing so is not engaging in the trivial, of rising about banalities, be they petty personal gripes, minor matters of taste, indulging in gossip, bickering, feuding (within the movement) and being prey to the passions that the Stoics warned against. By becoming weak and failing to overcome our internal faults, we make ourselves non-serious as a movement and devalue our beliefs and our work.

3) Ambition. We need to overcome ideas, individuals and institutions that are discredited through the force of our courage and achievements. We cannot be complacent with regard to superiority over others. This means guarding against repetition, laziness and rote responses. We have to challenge ourselves to do better and constantly strive to lift ourselves and others in our movement by working harder, knowing more, sharing information (by being generous) and seeking to apply our discoveries (or rather, as perennialists, that should be “re-discoveries”) to more areas.

4) Solidarity. This might also be called conformity or in-group bonding. We are aware of the tendency of those who wish to dissolve concerted opposition to use hyper-individualism as an ideal to atomise the core of a potential rival elite. To ensure we advance our values, we expect that anyone in the movement either publicly support or not oppose those values. That can be judged through the artist’s work or his public statements. The movement retains the right to disassociate itself from individuals who do not conform to this. This may or may not be made explicit publicly.

5) Quality. This is the hardest principle to enforce, as it requires a high level of discrimination, as well as personal tact and compassion. Although according to principle 1, we should welcome those makers who express solidarity and conformity, we must also exercise judgement that requires us to exclude, postpone, defer and omit. We must demand that the arts of our movement achieve a certain threshold of competency, ingenuity, truthfulness, integrity and compatibility with our values. We should not be afraid to refuse submissions to public displays or publications, while at the same time appreciating the effort and commitment of makers who currently fail to reach our standards. This may be ameliorated by having different levels of participation in public associations – for example, members, invitees. We must cultivate discrimination and connoisseurship through a body of published criticism and publications which share the best art we can produce, which will help to broadcast our standards and raise the bar in terms of production.

6) Independence. The movement must resist the interference of the state and quasi-state actors, such as organisations (charities, NGOs, large corporations, lobby groups) affiliated with the state. As I discussed regarding the setting up of an arts venue, funding or representation in decision making by such bodies makes a movement vulnerable to overt leverage or covert subversion. Funding should ideally come through blind trusts, anonymous donations, crowd-funding and commercial activity. Large donations should come without any conditions other than providing for publications, exhibitions, documentaries etc of a high standard. We should aim to establish our own channels of dissemination wherever possible and act with generosity to allow orthodox newcomers access to these channels.

7) Authority. Our authority as leaders in a renewal of the arts depends on our exercise of the above principles, the truth of our values, our personal conduct and the high quality of our work. We need to toughen up and offer apologies only when we respect the interlocutor and recognise a genuine fault – we must never offer strategic apologies because it depletes our moral authority and the credibility of our speech. We can engage in dialogue, even when we see our interlocutor cannot be moved because it is the audience who can be persuaded in private by what he hears. If we set a moral example, then we add ethos to logos and pathos in our presentation.

This is how a movement might comport itself effectively. It says nothing about the principles or aesthetics, outside of implicit values of comportment. That will be left until later. I say nothing about the advantages and disadvantages of having a membership scheme for the movement, as that is complicated. It advantages the movement to have an inner core of an old guard, elites and decision-makers as a vanguard and outer group of followers, imitating, disseminating and contributing as and when they can. A thriving movement needs this separation and needs to have a flexible and dynamic structure that allows replacement of personnel within the top cadre (the circulation of elites, as Pareto would put it), as well rewarding secondary followers and supporters.

I offer these guidelines for discussion and correction.

For what may be obvious reasons given the name of my journal, I think about these issues often and I'm glad to know that someone is doing such fine intellectual work on them as you.

It seems that the foremost obstacle in the present is that there are no discernible movements going on of any kind. It's one thing to have a Salon des Refusés when there's a recognizable hegemonic, old-guard style going on in French painting at a time when art was valued by the public. Now we have outsize, maybe absurd levels of pluralism in a time when visual art is largely an afterthought in the public mind. It's a wildly different dynamic.

I know of a single instance in which the rebels had to fight for the freedom to be left alone by the forces of institutionalized progressivism, and that is the Wuming Painting Collective in Beijing. The work they produced is good but not groundbreaking like the Impressionists, surrealists, symbolists, and Viennese Secessionists were at one time. Possibly the last dissident art movement of any note was the Stuckists, who were specifically opposed to conceptualism. I'm still making up my mind about Meow Wolf, but they did perform a viable end-run around the institutions.

My own focus of opposition is on bureaucratic culture. That jibes with your intention to disdain "the interference of the state and quasi-state actors." There needs at least to be an independent support network, and given the extent of contemporary bureaucracy, that may mean extremes such as independence from state money itself, which now possible through cryptocurrency. Wuming, the Stuckists, and Meow Wolf share an awareness of how to produce work that is comprehensible to people who don't have a degree from Yale or Slade or whatever; I believe that consideration is necessary, though not to the detriment of ambition or quality.

There is much work to do. I'm heartened to see your contributing to it.

This is an excellent, well thought out starting place. I found nothing to disagree with, and much to agree with very strongly. With the established institutions in various states of disarray and decay, it's on us to offer a compelling alternative vision - the best propaganda for which is beauty and virtue.