The Art of Beksiński and the Tragic Vision

The paintings of Beksiński give us an insight into human nature and take on characteristics of what is called "the tragic vision".

In the book A Conflict of Visions (1987) by Thomas Sowell, the author effectively summarised two contrasting approaches to human nature and politics are set out. These two visions – called the utopian and the tragic – lead to differing political approaches. While essentially temperamental positions, they have accrued bodies of literature and theory to support each and can be expressed intellectually and artistically.

The utopian vision is that of man compromised by circumstance, expressed most notably by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It states that societal inequity and injustice are caused by law, economics and material circumstance. Man is by nature social, co-operative and altruistic and is made selfish by example and situation, as he seeks to preserve himself and his family. Just as man evolved from older species and developed civilisation, so man’s nature can also evolve.

The tragic vision of humanity is that man is compromised by his inherent nature, be that God-given or evolved, and that his destined to be imperfect and flawed. Whether that flaw be called animalistic inclination or sinfulness is a matter determined by the intellectual framework of the speaker, but these descriptions overlap.

The utopian vision leads to the unconstrained approach, which says that - given sufficient knowledge, technique and political will - these faults may be reversed. If such a society were to be maintained and improved then man’s full potential might be harnessed and even (all other things remaining constant) permanently altered. Men’s actions are determined by their experiences and situations; good and evil (in terms of individual nature) are fallacious concepts. Social justice can be delivered when it is overseen by those provided enough knowledge, expertise and time, who can generate a fairer society, measured in terms of equality of outcome. This is the view of the liberal, social progressive and socialist. It is articulated by Karl Marx, who saw the improvement of society through cyclical economic progress as the harbinger of a man liberated from the bonds of want, inherited position and superstition.

The tragic vision leads to the constrained approach, which recognises that due to whatever causes, man’s weaknesses are universal, internal, persistent and – although potential remediated by instruction, example and circumstance – are ultimately ineradicable. All action is a matter of trade-offs regarding costs and benefits, aspects of personal freedom must be compromised for the benefit of all. Justice is a matter to be dealt with at an individual level and requires individual culpability. Man’s desires and aversions are so deep rooted and persistent over generations that they must be constrained by law and custom. The constrained approach says that even given increased data and power, an elite can never reshape human nature, which is eternal. This is why the wise elite do not believe the unconstrained approach is viable or moral. This is the view of the major religions, the conservative and the reactionary.

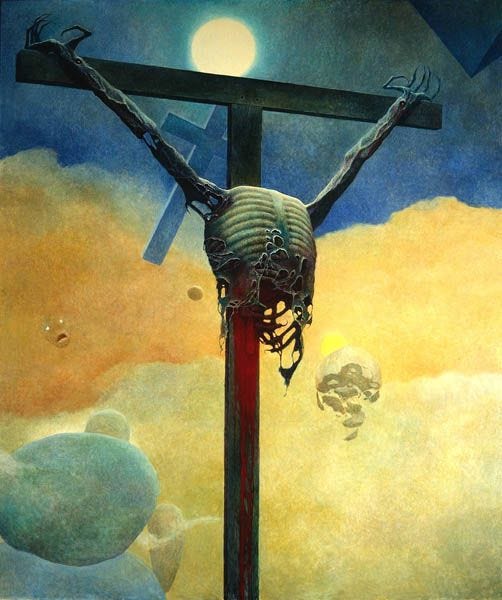

When we look at the bleak dreamlike visions of Polish painter Zdzislaw Beksiński (1929-2005) one receives impressions of deep pessimism and isolation. We find ruins, inexplicable structures, constructions that stun us but offer little shelter, sustenance or comfort. His crucifix forms present us with the suffering shorn of the redemptive purpose or the promise of resurrection found in the crucifixion of Christ. The weathered condition of Beksiński’s beings indicates prolonged suffering, an absence of relief, a dearth of loving witnesses. We are overwhelmed by the absence of relief and transcendence. Overall, we can say that Beksiński’s images of suffering, isolation, entropy and destruction correspond to the tragic vision of humanity.

This pessimism makes Beksiński’s art more closely aligned with the tragic conception of human life as being inevitably freighted with suffering. Although his art lacks the promise of redemption, it has the religious character of art that acknowledges religious teaching that pain and death must be endured and that (temporary, contingent) earthly relief tends to disguise this truth rather than providing any solution to anguish. Comfort of human (or humanoid) company does appear fleetingly in Beksiński’s painting, but it does seem brief consolation rather than lasting consummation of a union of souls. It is difficult to place faith in the power of society when we get no scenes of group activity, functioning settlements, working machinery or habitable locations – or at least, these phenomena in forms we recognise them. Death takes precedence over birth; where growth is seen, it is of alien entities that are forbiddingly unfamiliar. The leafless tree is common and the fruit-bearing bough absent.

It is not merely the pessimistic tone and existential character of Beksiński’s art – whether or not it is a landscape/marine or a figure/portrait – but the universe portrayed that makes Beksiński’s art commensurate with the tragic vision. The desolation and alienation are the product of a visionary who sees the darkest aspects of life and does not shy away from depicting them. He feels compelled to exemplify human beings’ plight as insignificant and subject to dissolution. The audience is cocooned in a world of plentiful food, state healthcare and protection from the environment, needs to be reminded of the sublime, incredible and awful. There are no true individuals in Beksiński’s universe, no sense of personal exceptions or great figures who overcome strife.

We encounter a place that powerfully impresses us and that we respond to subjectively. The viewer is acknowledged through the care applied to make scenes both incredible yet also comprehensible and legible. We can create an imaginary tour of what we see. We can describe what might be out of our line of sight or what might be inside those gigantic buildings. We can imagine dusk or the acrid smell of smoke. There is verisimilitude even if not realism as such. Beksiński gives us enough information to inhabit these places and, should we engage deeply enough, we find ourselves in a place that serves to remind us of our insignificance, reinforcing wonder and despair simultaneously. Confronting such responses asserts the truth of the tragic vision. It shows that, no matter how much we consider ourselves to be masters of our lives, our eternal nature is to be humbled and awed by a world that is indifferent to us. While Beksiński seems cleave to the humbling teachings of religion – or at least to that temperamental outlook – he subscribes to no theism, no interventionist god, no supervening angels, no salvation through prayer, no agent who will relieve our pain. He is a religious man with no faith; there is nothing in these paintings that gives an inkling of humanist hope. In the artist’s unwillingness to entertain salvation or escape, he allows us no respite except the defeat that is to be found in turning away our gaze from the horror and pitiful scenes he has fashioned.

Just a quick thanks for this work. This is a completely new name to me and the man and art seem fascinating.