Techno-Romanticism: If man could outlast a mountain

From art exhibitions to rock concerts, Techno-Romanticism explains how we venerate Romantic transcendence but experience events through the digital screen.

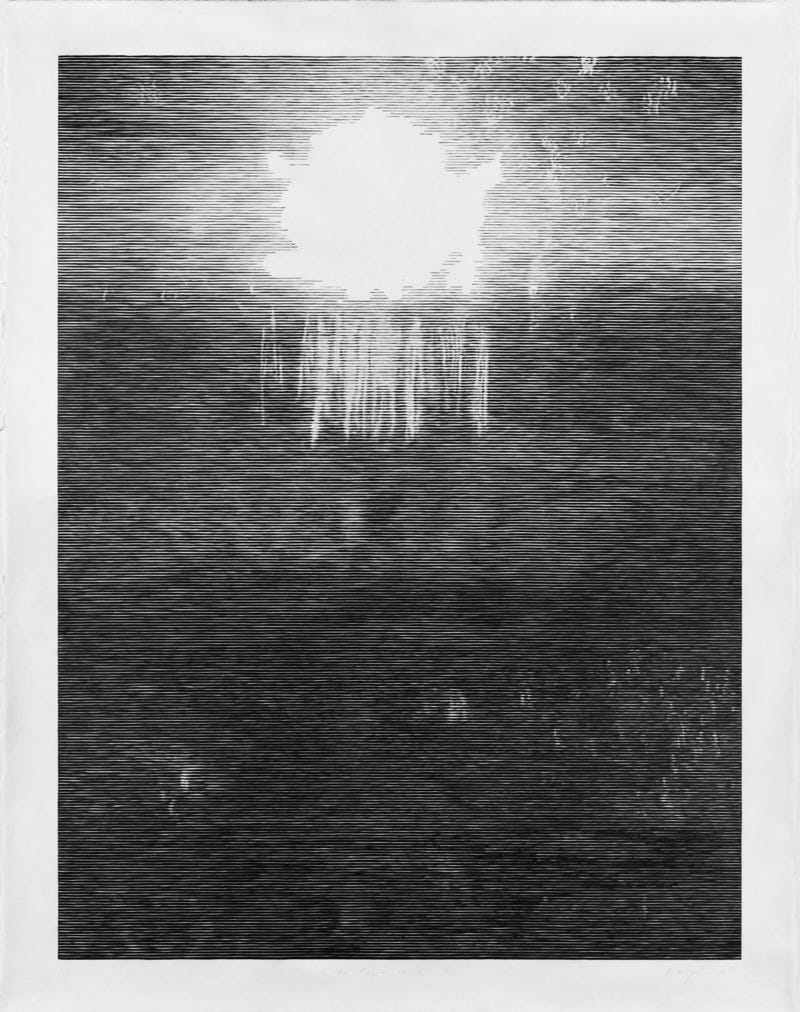

It is curious that perhaps the world’s leading Romantic artist is also the best living printmaker. Christiane Baumgartner (b. 1967) is a Leipzig-based printmaker who has been exploring the world through heavily processed imagery, both of urban environments and nature. Baumgartner’s current solo exhibition is Sunken Treasure (Cristea Roberts Gallery, London, closes 8 March 2025) presents new prints on the subject of reflection, glare and haze, set in forests or on the Baltic Sea coast.

The exhibited prints are woodcuts on a large scale; they have been created through filters that have reduced recognisable imagery to a basic minimum. The scenes in Sunken Treasure are in themselves not classically beautiful; they lack dramatic composition and incident; there is no staffage. They show moderate waves under cloudy skies and the haze of sunlight through mist within a wood. They are chosen to be striking through intense tonal contrast and the contre-jour effect, but they are not pretty or sublime, nor were they intended to be so. In large multi-colour prints Pearls and Diamonds, the imagery becomes so diffuse and hard to read it becomes abstract, although not arbitrary, led as it is by the source, however uninformative. Multi-sheet sets of transfer monotypes – made by placing a sheet on an inked plate and rubbed the back of the paper, which produces pastel-like clouds and bars of speckled colour; the process is repeated a number of times on the same paper but different colour inks – allow Baumgartner to present pure abstraction, untethered to source or concrete imagery.

Baumgartner’s art presents the seascape as a field of nature viewed and comprehended through digital technology, principally the grid of horizontal lines that one finds in screens, principally cathode-ray televisions. Not only are there horizontal strips of tone, there are lens flares – indisputable artefacts of photo-mechanical capture of image. While viewing the pictures, we are constantly reminded of the artificiality and optical difficulty of reading what is on the paper before us. We are never freed from ourselves by pure pleasure or complete immersion in a presented world; the mental ingenuity to turn serried rows of crude marks into intelligible views of deep space keep us from relaxing.

Artists working today who feel antipathy towards Post-Modernism and desire to engage with Nature (especially through the Romantic tradition) would do well to consider Baumgartner’s art. She has managed to approach the natural world in a non-ironic, serious way and kept in mind antecedents such as the German and Northern Romantic painters, while acknowledging she is of our age and can be none other than an artist of the early Twenty-First Century. Her art is of natural forms but it is filtered through technical devices that permeate our lives. She has extended the Romantic and Symbolist landscape but not resorted to anachronism or sentiment. She has resisted the temptation to quote (or even paraphrase) in order to make her art gain authenticity through lineage. Her art earns its place in that lineage through being true to its subject, true to itself and true to its age. Baumgartner’s prints are Techno-Romantic is character.

Techno-Romanticism is an approach to the wonders of nature that is indirect. It admits that today’s observer is a product of his time, that he has been conditioned by mediated experience, wherein Man encounters the object of his study through a photo-mechanical medium and this colours his response to Nature, even when he is in the direct presence of Nature. The viewing of a famous mountain is simply the latest iteration of the experience of a subject viewing this view; previous iterations have been in photographs, film, television or (recently) computer-generated imagery. When he sees the “original”, it is in the light of his experience with reproductions, mostly of a photo-mechanical character.

The Techno-Romantic is related to Walter Benjamin’s essay regarding the aura of a work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. However, it is a more diffuse matter. It is not simply a question of the authentic ur-image being disseminated and that this changes a person’s understanding and valuing of the original, then (consequently) how one approaches art and its role in an era of late capitalism. Techno-Romanticism is an attitude and worldview that comes about due to a subject becoming inured to the experience of distanced viewing and being unable to experience phenomena without a) engaging in recording, b) mentally comparing the viewing to recording, or c) feeling a pang of disappointment at the experience not being recorded or recordable. The aspect of technological processing and recording transforms the viewing experience because the brain is wired to received indirect processed material rather than the raw unprocessed object in itself.

In extremis, the Techno-Romantic man can only (like a Sadean voyeur) process the real through the lens of a telescope reversed, so that he views the object miniaturised and held within a glass, allowing him the experience of nature as contained, compressed and something he can hold within a hand. Like the eyepiece of a telescope, the laptop or mobile-telephone screen can confine nature, making it handheld, portable and (ultimately) controllable. The image can be manipulated, recorded, stored or erased.

It is this Techno-Romanticism that we see manifest when concert attendees watch live performances through their mobile-phone screens and when cultural tourists who jockey for position to photograph a famous work of art (with or without their spouse or themselves in the frame). Techno-Romanticism causes the subject to venerate the Romantic transcendental power of the authentic, but seeking to capture and experience it through technological means. There is a devotion to the beautiful sublime but an inability to absorb it directly, through pure sight and for that to be recorded in the unreliable data bank of the human memory. Techno-Romanticism is a state arrived at when Man seeks fusion with Machine, to commit his memories and sensations in an unalterable fixed state in a technological apparatus. It is a cry against the fallibility of memory; it is defiance of the truth of memento mori and – at heart – a rejection of the truth of human vulnerability, inconstancy and mortality. It says that if a man’s experiences can be preserved in digital form, his consciousness might outlast his frame; he might become as durable as stone; he might outlast a mountain. Yet, we know how foolish this conceit is; digital data rarely lasts intact for a decade, let alone a lifetime. Nevertheless, we dream such a thing might be possible – a modern professional of faith in non-spiritual immortality, as a ghost in the machine.

If that seems an exaggeration, consider the Romantic poets of the 1800s. For them, the experience of standing on a mountaintop in a storm made them feel that they were “completing Nature” by acting as a witness or a conduit for the power and drama. It raised the question of whether the beautiful or sublime could exist without a subject to experience and respond to either. For the deist, agnostic or atheist, the idea that Man was a component necessary for the beautiful or sublime to exist was only one step away from Man as beautiful and sublime, the cause of the wonders of Nature.

Baumgartner is a not only a skilled artist, she is an important figure because she is able to intelligently negotiate the technical imperative (that is to invent and excel, as every groundbreaking artist must do) while taking on the mantle of the Northern Romantic artist and not resorting to the tricks that might bolster that task. She does not adopt an old style or imitate the imagery of Romantic masters; she adopts an ancient medium (of woodcut) but incorporates elements that are new; she does not shy away from the fact that her working practice includes photo-mechanical image capture. Honesty is a prerequisite for an artistic greatness. It seems that Christiane Baumgartner and her prints have that quality (and many other qualities) which commend artist and art to us.

Nicely observed.