Power and pastoralism

Two exhibitions of Minimalism and Ruralism, prompt thoughts on what we expect of veteran artists and what they expect of themselves.

I. David Inshaw

The latest exhibition of David Inshaw (b. 1943) (Redfern Gallery, London, closes 25 April 2025) focuses on the landscape. With the exception of nudes and portraits, the landscape (and especially the peopled landscape) has been Inshaw’s primary subject since his artistic maturity, which commenced around 1970. In that sense, there was nothing unexpectedly new in this current exhibition. For over two decades, the landscape of Wiltshire and Dorset have been Inshaw’s locus. The views around Pewsey and the Wiltshire Downs dominate. A notable recent piece is a snowscape. The small irregular snow-covered fields are given different tints, enlivening through variation a scene that might otherwise have been formulaic or merely pretty.

The exhibition gathers together works from the 1990s up to today, mainly landscapes. Inshaw’s work is generally at its best when it is larger. Whether it is because Inshaw is prompted to raise his game when takes on a task with higher stakes or because Inshaw has the opportunity to select among a number of existing sketches (selecting the most striking composition) is an open question.

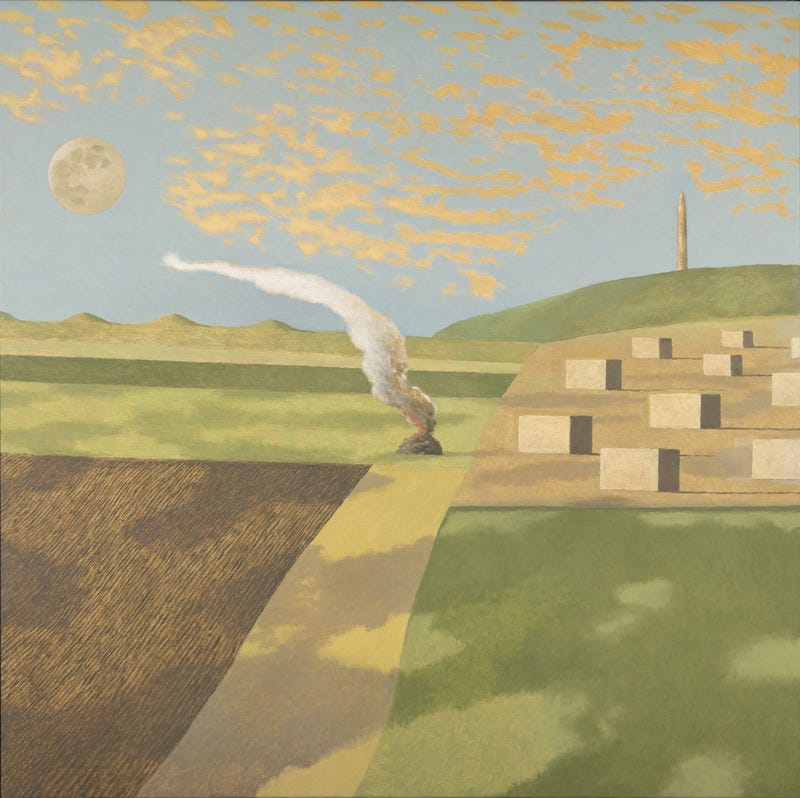

Inshaw’s great breakthrough (c. 1970) was when he combined tight detail, large size, repeated patterns and carefully calculated surface textures. Although the artist has been able to allow his more relaxed touch come to fore – how can an artist not gain through experience an understanding of how to achieve effects more efficiently? – his recent art suffers from handling that too often appears indiscriminate. Nonetheless, there is plenty to enjoy in Inshaw’s new art. The pictures of trees in blossom never stray into cliché. The paintings of landscapes with the moon have a mystical air and a genuine engagement with the supernatural hold the lunar spectacle has over us.

An unexpected highlight are the firework paintings, especially of bonfires. Despite having previously seen some, either the setting or selection (or perhaps something changed in me) suggests they may be the highlights of his work since the late 1990s. I bridled less at these paintings having a square format because of their strange and abstract qualities. I have previously written about the unnaturalness of the square format for pictures that are not primarily decorative. These nocturnes earn their peculiar abnormal formats and indeed the 1:1 ratio contribute to the unsettling force of the scenes.

In the bonfire paintings there is a certain daring in the handling and image making, where patches of paint vie for attention against a dark ground and elements take on a raw potency in their abstract qualities. In the largest, they have an imposing quality, full of mystery. Inshaw seems able to take risks and use looseness of application to its fullest advantage in these pictures. In some odd ways, these reminded me not only of English abstraction of the 1960s and 1970s but of Ivon Hitchens’s small landscapes of the 1930s and 1940s.

The few pictures with figures in landscapes do not feel out of place. Of Inshaw’s animals, his paintings with cats are appropriately dry and reserved, with a dash of wit. When Inshaw paints birds, they tend to be most effective when seen in the distance. The large canvas of a jet fighters flying low over a hilly landscape effectively juxtaposes the sleek sturdy machines with the timeless rumpled topography of England. If one were compiling a monograph on the artist, this painting would go along side those of the neolithic chalk figures on hillsides as classic images of England. There is still to be written a definitive text on Inshaw as an English painter and as a pictorial chronicler of England.

II. Richard Serra

The last works by Minimalism sculptor Richard Serra (1938-2024) are currently on show in London (Cristea Roberts Gallery, London, ends 26 April 2025). The exhibition displays the artist’s characteristic vigour, indomitability and impassiveness. Serra’s usual medium was steel sculpture, only minimally manipulated to accentuate sculptural qualities. The planar aspects of the slab structures is apparent in these hybrid works which we can call prints.

Oil pastel and silica gel are forced on to the surface of paper, applied through a stencil, leaving undifferentiated patches of black. This was done several times, allowing the first layer to dry. The result is a roughly textured plane of pure black, which covers the majority of large sheets of off-white Japanese paper, reaching over two metres in some dimensions. These monochrome pitted fields are very similar to the rusted steel surfaces of Serra’s sculptures, something that will be apparent to those who have seen Serra’s sculptures in person.

The artist said, “Black is a property, not a quality. In terms of weight, black is heavier, creates a larger volume, holds itself in a more compressed field. It is comparable to forging.”

These do count as prints, even though they are handmade, have not been produced purely mechanically and have not been made through a press. The process of inking by hand is usual in printmaking and the stencil is common to pouchoir and screenprinting techniques. The use of a standard stencil design and the production of a uniform edition (in this case up to 56 per print for some pieces) produce nearly identical artefacts (the word “pictures” seems inappropriate for these objects), this means these works can be classified as artist’s original prints.

The titles Hitchcock (2024) and Casablanca (2022) refer to classic films of the golden age of Hollywood cinema. Perhaps the spackled areas of darkness could be a reference to the dark areas of projected black-and-white films. The large surfaces of the paper – which can seen naked past the edges of the black ink – seem equivalent to cinema projection screens, with the black forms a type of obstruction of light. In the slight tangents between paper edge and ink edges we can see something similar to misalignment between the edge of a projected film and the screen on which it appears. However, as this is a quality shared with many Serra prints and drawings, which do not refer to films. The shallow curving arcs and tilted rhomboids are visual analogues for Serra’s sculptures.

The prints present considerable difficulties in terms of presentation and preservation. Casablanca weighs almost 10 kilograms before mounting and framing. The framing is float-mounting of the sheets on boards in unglazed frames. Protecting the surfaces of these valuable prints from people touching them and from dust (as the surfaces are uncleanable) will compel collectors to put them behind glass, which would be a shame but understandable. The sculptural quality of the light on the surface and being able to get very close to the prints makes the viewing experience fascinating.

What is the viewing experience like? Invigorating. It is like encountering something carefully made that is visually absorbing but which refutes analysis, like part of a building or a component for an industrial machine. An obvious comparison would be one of the late Rothko acrylic paintings and the Black Paintings of Ad Reinhardt, but Serra’s prints are more imposing presences. To apply aesthetic considerations to Serra’s prints seems inappropriately dainty. They have a force that repels refined appreciation and instead they provoke a visceral reaction. Just as Serra’s sculptures dominate space, with their weight and precarious balance threatening us, so his prints demand attention and have an undercurrent of intimidation, yet without the threat of physical danger. It is a peculiar experience -pure and somehow energising – for an art gallery and one that only derives from abstract art, mostly monochrome. It is hard to quantify and worth a revisit. In the meantime, try visiting and experience it yourself.

III.

Both exhibitions show how veteran late-career artists can develop core themes through slight extension and variation.

Inshaw’s ruralism has expanded to include developments of modernity and their intrusion into the landscape that is seen as a redoubt of the English experience. This was always implicit in his pictures of the early 1970s, which included the cultivated garden and figures of the time in settings that blended the ancient and pastoral with material that was from the Twentieth Century. Like all of the Brotherhood of Ruralists, Inshaw’s Ruralism was predicated upon (as much as it was a reaction against) photorealism of the 1960s. The addition of elements such as jet planes, coastguard stations and World War II sentry boxes is completely of a piece with his 1970s Ruralism, and is by no means a recent development. What we see as a new factor is the more uniform handling of paint and thinner paint (with occasionally pinkish undercoat showing through), showing that Inshaw is working faster. This tendency towards brevity is a by-product of confidence and experience but also an awareness of the shortness of time that comes to the ageing artist. Of course, I wish Inshaw many more years of good health and productivity, but it would be vain to suggest that an artist now aged over 80 does not have time’s wingèd chariot far from his consciousness.

Serra’s prints were a comparatively late undertaking. Working to commission rather than producing single or editioned sculptures gave Serra plenty of time to consider his practice in the form of speculative drawing – of which his prints are the most public form. Printmaking gave the artist a way of producing editioned work that was practically identical to an autograph drawing but did not require draining effort or the necessity of travelling to a location to execute that piece. It was a solution to a problem that all successful artists have: to what degree can work be delegated while retaining the essential qualities the artist cultivates and which are characteristic of him? Through set procedures and a designated template made by the artist, prints-as-drawings could be produced that were fully faithful to the sculptor’s intentions. This delegation is not so far from the necessary work of foundries and construction firms that manufactured and installed his steel sculptures.

Incremental advances and the development of variations are what we expect of artist’s throughout their working lives. What do we expect of late-career artists? The oft-discussed late style is freedom in imagination and technique, with an associated grandeur and emotional richness – largely related to human tragedy and encroaching mortality. Rembrandt and Titian are considered prime examples of artists with a late style. However, they are artists who developed in a dynamic manner. Inshaw and Serra are artists who developed rapidly before their maturity and since then have not changed their interests and approaches significantly. In these cases, the gradual expansion of materials and subjects as a late stage is to be expected. If there had been a sudden spurt or divergence it would have been an oddity for these artists. In that respect these two dissimilar artists are very similar in their artistic trajectories.

David Inshaw: Thinking the Landscape, Redfern Gallery, London, 26 March-25 April 2025

Richard Serra: The Final Works, Cristea Roberts Gallery, London, 13 March-26 April 2025