Philip Guston, Dissenting Painter

Reviewing reissued books (for The Jackdaw) in the run up to a large exhibition at Tate Modern, London (opens October), led me to consider Philip Guston as a model of dissention.

Canadian-American painter Philip Guston (1913-1980) can be taken as a hero for dissenting artists. How so? Surely a Jewish member of the New York intelligentsia, friend of noted authors, supporter of unions, politically left in outlook and anti-war, could hardly be described as a dissenter in the New York art world. After all, looking at the direction of travel of political and social conventions in the USA in recent decades, it seems Guston’s liberal outlook won the day. I would not argue with that interpretation but it leaves out the most important part of being a painter – that is, the nature of the art one makes, endorses, shows and thinks about daily for most of one’s life. With respect to painting, Guston was a dissenter who risked his reputation and livelihood because he chose to revolt.

Born in Canada, Guston studied painting in Los Angeles in the 1930s. He visited Mexico and painted an anti-Fascist mural. Like the Mexican Muralists, he was a socialist and saw his art in terms of the necessity of social engagement, both in subject and reception. When the WPA commenced, he took up a position in the Mural Department of the WPA. Paid to decorate buildings, Guston had a chance to experience the camaraderie of working in teams that art that would reach a wide public immediately, with a degree of security and social affirmation provided by Roosevelt’s New Deal. Later, like many young artists fostered towards a professional career by the WPA, Guston gravitated to New York, where he joined the scene in Greenwich Village and Union Square. He joined a group of competitive artists who shared common goals and spoke a shared language of Modernism. When Abstract Expressionism made inroads in commercial galleries and the press, Guston contributed his paintings, which were dubbed Abstract Impressionism. He won the Carnegie Prize for painting, the Guggenheim fellowship and Prix de Rome and went on to receive the honour of a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in 1962. Much of his income came from teaching positions in art schools.

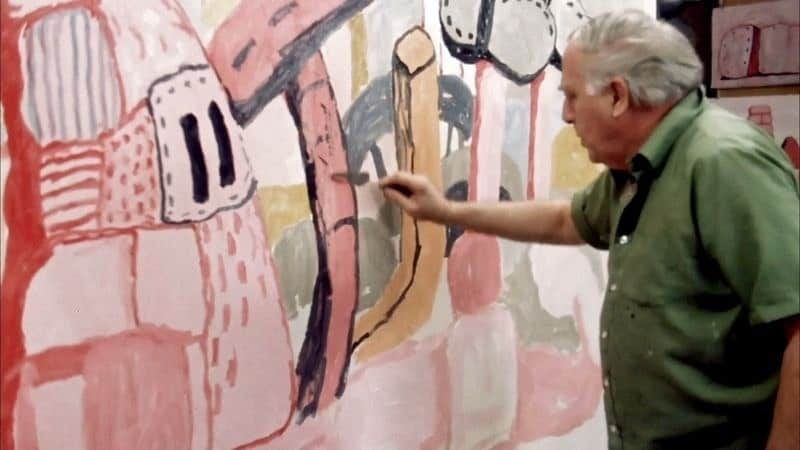

All of this shows how Guston was respected by the cognoscenti, appreciated by his peers and firmly at the centre of his professional field. Although at outlier socially in the USA as dedicated liberal and Modernist, he was those respects perfectly standard with regard to his artist peers and appreciators of abstract art. He counted many poets, authors, photographers, painters and sculptors as not only colleagues but personal friends. When, in the late 1960s he started to play with inchoate forms, he was groping his way to figuration. Then, in 1968, at the height of Vietnam War, frustrated at the distance between the conventions of Abstract Expressionism and his compulsion to speak about real objects and actual events, Guston allowed the images back in. Guston rejected pure abstraction and began to paint figures, buildings, furniture, rooms, books, shoes, food. He was liberated from liberation and squalid reality intruded in the etiolated space of art. (This was no doubt also a reflection of his social-engagement of socialist mural painting in the 1930s.)

Guston declared, in a private note, that “American Abstract art is a lie, a sham, a cover-up for a poverty of spirit. A mask to mask the fear of revealing oneself. A lie to cover up how bad one can be. Unwilling to show this badness, this rawness. It is laughable, this lie. Anything but this! What a sham! Abstract art hides it, hides the lie, a fake!”[i] He rejected the assumption of purity that Clement Greenberg’s theory (of art’s inevitable drive towards autonomy and specialisation) entailed. “There is something ridiculous and miserly in the myth we inherit from abstract art. That painting is autonomous, pure and for itself, and therefore we habitually define its ingredients and define its limits. But painting is ‘impure’. It is adjustment of ‘impurities’ which forces painting’s continuity. We are image-makers and image-ridden.”[ii]

Painting real things and dealing with experiences – albeit in a painterly, simplified manner – added richness to Guston’s output. He could talk about banal daily activity but add a dimension of existential anxiety to it. The bean-head that stares at the bottle confronts the unhealthy hold of alcohol. The smoking head in bed admits to cravings and weaknesses that amount to compulsions that fill its world. When Guston painted books, scrolls, fires and cauldrons, he could approach perennial motifs that hold religious power in our imaginations: race memory, archetypes and essential symbols. These are ideas and symbols that dominate our mental landscapes. For those artists who wish to draw on the compelling energy of real objects with symbolic power, they should look to Guston, even if they ultimately conclude his style, handling and aesthetic framework are not compatible with their aspirations.

When he exhibited these paintings in New York in 1970, it was seen as a betrayal. Guston was considered to have stabbed Modernism in the back. All of the battles that Modernists had fought with critics in the 1930s and 1940s, pushing back against public mockery and official disdain, had been for naught, his colleagues thought. Guston had degraded himself and art; he had sided with those anti-Modernists (including traditionalists, Regionalists, social conservatives and (worst of all) Fascists). He received a vicious backlash. The exhibition was savaged, little sold and Guston realised his gallery, Marlborough Gallery, no longer had confidence in his art, so he left the gallery. There were serious consequences for Guston following his conscience and deciding that art had more meaning when it was founded in the objects and spaces of the real world. Friendships were irreparably broken, support networks severed. For the next decade – until mere months before his final exhibition and death – Guston experienced what has been described as “house arrest”, being shunned by the art establishment and existing in internal exile.

If any dissenting movement is to arise in the West, it needs to have artists who are willing to take risks, as I outlined on my article on artists as gamblers. Will there be artists who are able to separate themselves from the teat of the state[iii] and strike out with new art that embodies the beliefs they hold and that the governing elite fear and deride? Guston is a model for that because he had a powerful commitment to art that he loved, as well as his personal beliefs. Those beliefs may not be your own, but to decline to follow conventions that underwrite your livelihood and are a core belief of your community – and to do it in a public fashion – indicates an uncommon degree of commitment and strength of character. It is worth noting that Guston had reasons both artistic and political for thinking that the style of the day (by then promoted by the state and media as typically American and indicative of liberal freedoms) was, if not artistically bankrupt, then compromised and limiting. Rebelling after fighting (alongside colleagues) so many years to be taken seriously as an abstract artist, was a rare instance of public renunciation.

For those of us seeking to distance ourselves from the status quo, we shall need such conviction such as Guston’s.

[i] Undated, (1970s?), quoted, Musa Mayer, Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston, Hauser & Wirth, New York, 2023 (3rd ed., 1989), p. 234

[ii] Quoted, Ross Feld, Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, New York Review of Books, New York, 2022 (2003), p. 16

[iii] The WPA project had ended long before Guston’s 1970 exhibition. The reference to separating oneself from the state does not refer to Guston but to the artists working today in the West.

The Rockefeller family believed they could seduce modern leftist artists by coopting them. Commissioned murals, founded MoMA, etc. The idea was to present the West as a bastion of freedom. Therefore, enormous propaganda efforts went into the promotion of modernism in art (unnecessary to learn how to draw or acquire technical skill) and, later, racial and sexual equality.

Gloria Steinem worked for the Independent Research Service, a CIA front organization, in the 50s and 60s, meant to undermine communist youth festivals. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-gloria-steinem-cia-20151025-story.html

Congress for Cultural Freedom, main CIA arts front. MoMA heavily involved with Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs committee in 50s, CIA front headed by Nelson Rockefeller. MoMA’s International Program funded by CIA front Rockefeller Brothers Fund for $125,000, launched a massive AbEx push in Europe. “Twelve Contemporary American Painters and Sculptors” toured European capitols starting with Paris in 1954-5. Another, Young Painters, opened in Rome. Eisenhower called modern art a “pillar of liberty.” (Saunders, p. 262-72.)

MoMa’s International Program later expanded as the International Arts Council. Huge show “Antagonismes” opened in the Louvre’s Musee de Arts Decoratifs January 1960. Mark Rothko, Franz Kline and other New York School AbEx’s.

“Repudiating nationalist claims for Abstract Expressionism, in the 1970s [Motherwell] supported the English abstract artist Patrick Heron when he challenged America’s right to exert a monopoly in cultural leadership . . .” (Saunders, p. 276.)

“Ad Reinhardt was the only Abstract Expressionist (sic) who continued to cleave to the left, and as such he was all but completely ignored by the official art world until the 1960s.” (Saunders, p. 277.)

“Reinhardt roundly condemned his fellow artists for succumbing to the temptations of greed and ambition. He called Rothko a ‘Vogue magazine cold-water-flat fauve’, and Pollack a ‘Harper’s Bazaar bum’. Barnett Newman was ‘the avant-garde huckster . . .’” So, there was some sort of buyer’s remorse floating around. Reinhardt died in 1967.

I think it was a combination of former leftists who felt guilty about “selling out” and a vague sense of being used by the establishment for political purposes. Also, the 60s saw the beginnings of the Great Society, Viet Nam and a shift back to the left for the cool kids. In footnote 3, chapter 16, Saunders writes that the House Committee on Un-American Activities compiled a detailed list of communist artists of which Philip Guston was one. Whether he somehow discovered CIA involvement or not Guston had a violent reaction. CIA in that period was all over the place, including MoMA.

If you don’t mind, another point: Beginning in the 70s women artists would figuratively mutilate themselves in order to punish men. It was actually referred to as scatological art – part of the feminist vanguard. I’d suggest that Guston pretty much did the same with his own work once he discovered his association with the CIA mission. He needed to purge himself from feelings of betrayal to his previous political/social allegiance. This would explain his bizarre rage against his own AbEx work. His inner torment manifested itself by making really ugly (scatological) paintings to punish those who duped him – and to punish himself. Whoever heard of an artist raging against his former work like that? Normally, it’s just a natural progression. Happens all the time.