Peerless Peasant Bruegel

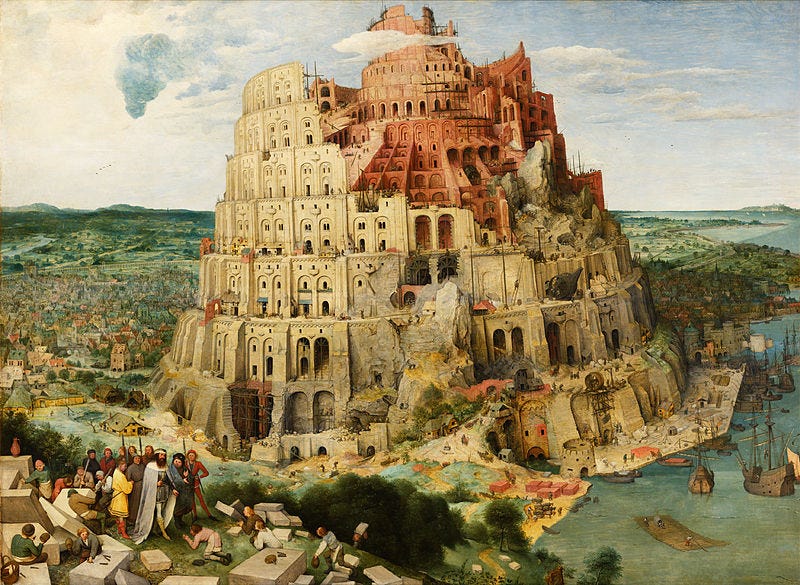

[Image: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel (1563), oil on wood, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, source: Wikipedia]

In the gilded hall of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna is a placard pronouncing: “The world’s first monographic exhibition on Pieter Bruegel the Elder collates three quarters of all existing paintings, as well as half of the drawings and graphics.” This exhibition (KHM, 2 October 2018-13 January 2019) presents the majority of the art of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525/30-1569) in time for the 450th anniversary of his death. KHM is home to almost a third of Bruegel’s extant paintings, so this is the natural location for this exhibition, which will not tour.

Bruegel was a painter of broad range: he made drawings, prints and paintings (and unlocated miniatures); he painted Biblical and mythological scenes, allegories, parables, vignettes of everyday life, landscapes, marines, ships, animals and character heads; he worked large and small; he painted grisaille and in distemper as well as oil paint; he worked from life and imagination; he had a talent for bringing the historical to life and an inclination to capture ordinary people. Within a painting he goes from grand to humorous without the satirical diminishing the profound. He has the eye of a reporter, the curiosity of a scholar, the detachment of a philosopher and the acid tongue of comic. He is an exemplar of the skilful political artist: when he turns the Massacre of the Innocents into a raid by Spanish occupying troops on a Flemish village he makes an intelligent analogy that both brings to life a Biblical episode and delivers barbed criticism of current events. There are viable claims for him being the first great humanist artist and founder of landscape painting.

All of this is on show in Vienna. We enter a grand gallery with walls painted burgundy. Later galleries are painted graphite grey and brown. To protect the graphics, light levels are low. Some might find them too low. Visitors shuffle around the dim cavernous galleries, parquet floor creaking like wicker.

Over 1552-4 the artist travelled to and around Italy, drawing as he went. Although a number of drawings on Italian paper are known, there seem to be no drawings made in situ. The dramatic landscapes seem to have been drawn on his return to Flanders, using sketches now lost. (Many drawings in older books on Bruegel have been shown to be the work of C16th followers and forgers.) Note that the drawings are artfully composed from various elements, thus are persuasive fictions using motifs taken from reality. Execution is brisk and confident, with curves, hooks, loops and other simple signs repeated to build texture and tone, much along the lines of Van Gogh’s drawing (though Van Gogh was inspired by Hokusai’s manga rather than Bruegel). These amalgam landscapes of Flemish figures and buildings in Alpine settings were the basis for prints and paintings over the remainder of Bruegel’s career.

Many of the engravings Bruegel designed (but did not cut) are shown beside Bruegel’s original drawings. It is easy to see from the regular curved hatching and clear outlines (quite different from the rapid stenography of the independent landscape drawings) that Bruegel understood well the necessity of clarity and consistency when designing for engravers. In contrast to the print designs, no preparatory studies for Bruegel’s known paintings have survived. One drawing of a gooseherd relates to a lost painting, only known through a version by Pieter Brueghel the Younger. Clearly, collectors and later artists had little interest in retaining Bruegel’s figure studies.

Early print suites of the Cardinal Sins and Virtues are influenced by Bosch. The sins are more entertaining than the virtues, naturally. The Boschian painting Dulle Griet (1563?) has been cleaned and revealed to be an unusually strongly coloured work. Dulle Griet is possibly a companion piece for The Triumph of Death (after 1562?), which is also here, and Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562; see my review, no. 121), which is not. All are oil on panel, 117 x 162cm, similar in tone and fantastic imagery; however they are thematically disparate. It seems too much of a coincidence that three visually similar paintings of identical size, painted within a year of one another, are not related by collector.

Of three recent attributions to Bruegel, two are here: a landscape drawing and an oil painting. (The third is a distemper painting in poor condition at the Prado, which was too delicate to travel. None of Bruegel’s four extant distemper paintings can travel.) These two attributions look strong. The Drunk Cast into the Pigsty (1557) is a tondo (a round panel – perhaps a dining platter?), showing a drunk being forced into a pigsty by an irate mob. The painting is signed, dated and was recorded in a contemporary engraving. The “new” drawing is an Italianate landscape.

Four of the five Seasons, Breugel’s sequence of grand landscape paintings, are reunited. The fifth has remained in New York; the sixth has been missing for centuries. (Michael Frayn’s Headlong is an accomplished comic novel about the apparent rediscovery of the lost Season painting.) It was apparently common in Dutch tradition to divide the year into six rather than our usual four seasons. After all the ribald incident, satire and profusion of figures, these large paintings with sweeping vistas and few figures are a breath of fresh air. These are essentially the beginning of the European landscape painting tradition, full of the wildness and wonder we find in Northern Romantic landscapes.

Side galleries are devoted to presenting scientific assessment and technical images which reveal how paintings were made, alongside photographic enlargements of details. Although Bruegel’s surviving corpus is not large, there are so many details which can be isolated that there is always something new to be seen in his work. Whole books have been compiled just of details from the paintings. Some alterations have been spotted using new imaging technology. In Peasant Wedding (1567) the codpiece of the bagpipe player was removed, as was a half-hidden couple copulating in the background. X-rays reveal that The Battle between Carnival and Lent (1559) has been similarly bowdlerised. Images of beggars, cripples and corpses have been painted over. Will Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, ever authorise removal of the risible bowdlerisations of the Massacre of the Innocents (Royal Collection; not exhibited) that turn murdered children into farmyard animals? Other changes include cropping. The Conversion of Saul (1567) lost its top and left edge at some stage, as comparison to an early copy by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, which shows the lost section. The catalogue includes a reconstruction of the original appearance of the panel. In some cases pigment changes (such as the fading of smalt) have altered the appearance of oil paintings.

In some respects the formidable catalogue (Bruegel: The Master, Thames & Hudson, 304pp, hb, £42) is a more approachable – certainly more convenient – way of appreciating the myriad detail of Bruegel’s paintings. (Consider the 230 figures in Children’s Games (1560).) It has been convincingly suggested that Bruegel learned miniaturist technique from Mayken Verhulst the wife of Bruegel’s master Pieter Coecke van Aelst. As Bruegel apprenticed as a print designer (and print cutter, though there is little by way of prints cut by him, notwithstanding the many prints he designed), it seems Verhulst taught the pupil how to paint miniatures. Although no miniatures by Bruegel have been identified, some were recorded as having existed. This will probably be the next area of intensive search for Bruegel scholars.

Miniaturist skill can be seen in two versions of The Tower of Babel (both 1563(?), both exhibited). In the KHM version, Bruegel included Flemish brick houses built on ramparts of the Tower, complete with washing hanging out to dry, livestock outside and window boxes of vegetables. That indicates the pragmatic character of local workers and their adaptability; it also presents us with the self-interest and indifference which would lead to the ruination of the Tower. Those touches are at once homely and cautionary in character, modes heightening each other rather than undercutting each other. In the Rotterdam version – a much more austere and sombre painting – there is a red baldachin, interpreted by Klamt as a criticism of Papal hubris (see my review, no. 138). According to the exhibition’s curators, microscopic study reveals no Pope or clergy under the baldachin, thus Bruegel was not criticising Catholicism but simply using a red device to fix viewer attention. They oppose Klamt’s opinion.

Despite his fine detail, Bruegel is never a fussy or precious painter. He breathes life into paintings through passages of vigorous visible brushwork and is content to be approximate where it does not count. Or rather, he uses these areas of pasture, foliage, sky and water to allow the eye to rest, so we are not overburdened by information as we are in Pre-Raphaelite paintings. This is an approach he shares with Titian, Velázquez and Vermeer – who can all be seen to advantage at KHM. I found myself hypnotised by the rough black clefts in the distant mountains of The Return of the Herd (1565). In Hunters in the Snow (1565) canny Bruegel has (in photographic terminology) “stopped down” the figures in the foreground, making them contrast strongly with the bright snow by employing little colour, few mid-tones and making their forms dark. (The “contre jour” effect.) In the background, atmospheric recession makes fields, mountains and sky merge in a blue-green haze of mid-tones. Thus Bruegel displayed his mastery of optical recession acquired through simple observation.

The catalogue includes extensive provenances, something to be welcomed. Many pieces not exhibited are reproduced in the catalogue, which summarises the scholarly consensus while including new ideas. The only true fault with the catalogue is the spreading of illustrations over double pages, something which renders images partly illegible. As long as this foolish tendency persists I shall not relent from criticising it.

View high-quality images at www.insidebruegel.net

Written 16 October 2018. This review was first published in print in The Jackdaw, December 2018. Every issue of The Jackdaw contains exclusive articles by me. Please consider supporting independent arts journalism by subscribing here: http://www.thejackdaw.co.uk/