I.

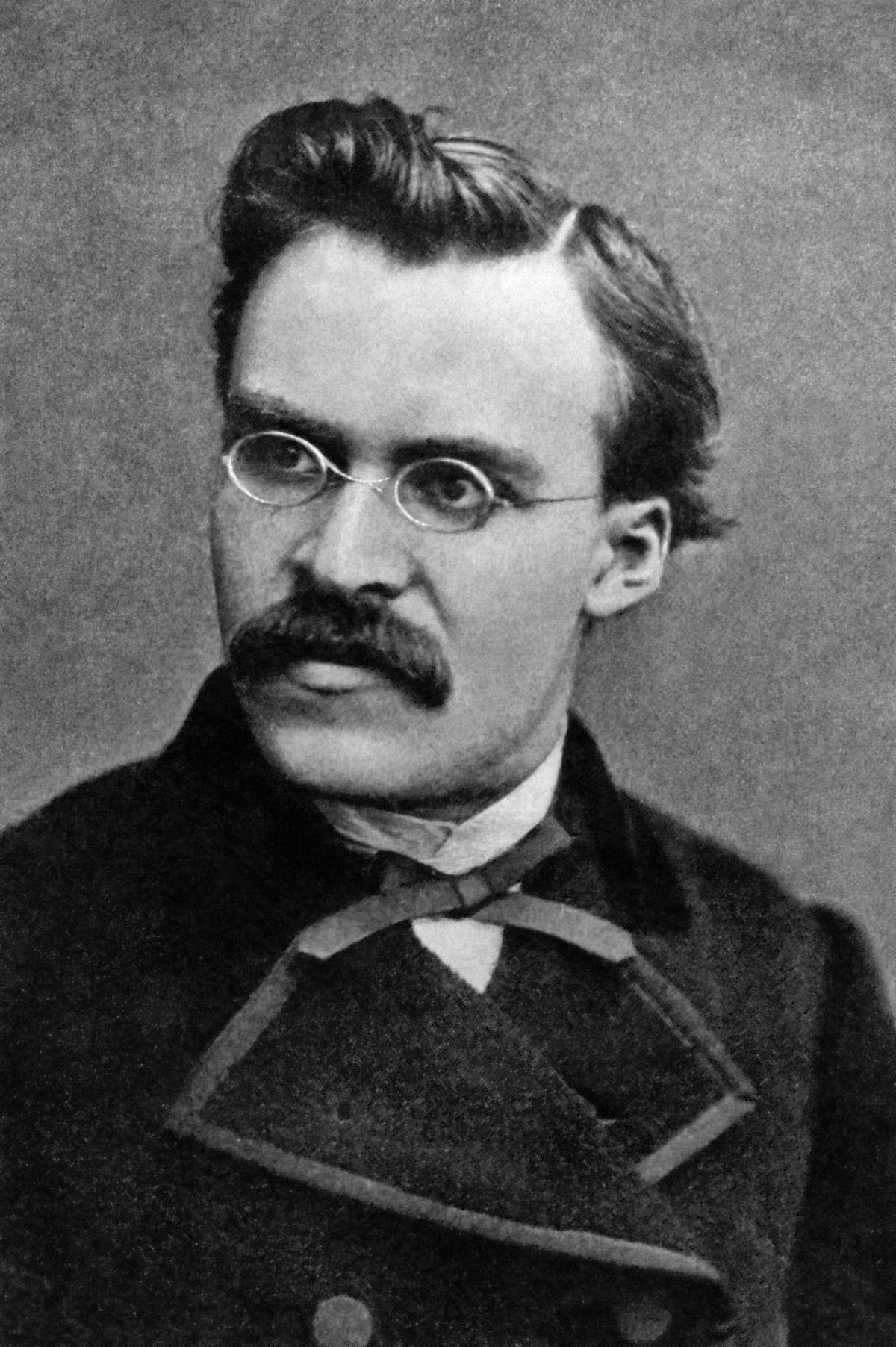

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) placed such a high value on aesthetics that his ideas on art form a core of his thought. In this respect he extends the interests of Schopenhauer, of whose writing he was a devotee in his younger years. Indeed, the ideas in his first book The Birth of Tragedy (1872) are suffused with a sympathy for Schopenhauer, one that would evaporate in the coming years. Nietzsche’s scholarship in ancient Greek – as a professor of philology – and fascination with ancient myths and customs led to his engagement with ancient drama as a paradigm of aesthetic accomplishment.

The Birth of Tragedy was Nietzsche’s analysis of human nature and the role of culture in embodying the conflicting (and complementary) sides of humanity. Nietzsche wrote that civilisation rests on twin pillars of temperament and response to natures which find expression in different art forms and modes: the Apollonian and Dionysian. The Apollonian (or Apollinian, named after Apollo, Greek god of light) spirit resides in sculpture, painting and epic verse; it is characterised by appearance, logic, individuation and clarity; it is rational, cognitive and ordered. (“Apollo is at once the god of all plastic powers and the soothsaying god. He who is etymologically the “lucent” one, the god of light, reigns also over the fair illusion of our inner world of fantasy.”[i]) The Dionysian (named after Dionysus, Greek god of fertility, wine and theatre) spirit resides in drama and music; it is characterised by the hidden, emotion, mass body and intoxication; it is irrational, instinctive and anarchic. (“Dionysiac stirrings arise either through the influence of those narcotic potions of which all primitive races speak in their hymns, or through the powerful approach of spring, which penetrates with joy the whole frame of nature.”[ii]) The genius of ancient Greek civilisation was that the Greeks had not only the Apollonian arts, that favoured lucidity, but festivals of excess – bacchanals, named after Bacchus, god of wine, another name for Dionysus – which allowed the expression of Dionysian values. If Apollo is god of dreams and Dionysus of ecstasy, the author of the tragedy is “dream and ecstatic artist in one”.[iii] These were combined. “The difficult relations between the two elements in tragedy may be symbolized by a fraternal union between the two deities: Dionysos [sic] speaks the language of Apollo, but Apollo, finally, the language of Dionysos; thereby the highest goal of tragedy and of art in general is reached.”[iv]

“The terms Dionysian and Apollinian we borrow from the Greeks, who disclose to the discerning mind the profound mysteries of their view of art, not, to be sure, in concepts, but in the intensely clear figures of their gods, through Apollo and Dionysus, the two art deities of the Greeks, we come to recognize that in the Greek world there existed a tremendous opposition, in origin and aims, between the Apollinian art of sculpture, and the nonimagistic, Dionysian art of music. These two different tendencies run parallel to each other, for the most part openly at variance, and they continually incite each other to new and more powerful births, which perpetuate an antagonism, only superficially reconciled by the common term “art”; till eventually, by a metaphysical miracle of the Hellenic “will,” they appear coupled with each other, and through this coupling ultimately generate an equally Dionysian and Apollinian form of art – Attic tragedy.”[v]

Nietzsche summarises classic Attic (Athenian) tragedy like this: “Tragedy interposes a noble parable, myth, between the universality of its music and the Dionysiac disposition of the spectator and in so doing creates the illusion that music is but a supreme instrument for bringing to life the plastic world of myth.”[vi]

It was the interplay between these modes within the art form of dramatic tragedy that gave the Greeks the greatness of their society, argued Nietzsche. The perfection of dramatist Aeschylus was undermined by the subversive rationalism of playwright Euripides and philosopher Socrates, whose examples led to the decline of the ideal form of tragedy. Nietzsche hated Socratic serenity for destabilising the balance of irrationalism and clarity that comprised the sacred practice of drama. The subsequent continued decline of tragedy, the division of the modes within the different arts and the failure of modern man to address both sides of his nature within society (specifically, the framework of the public arts) led to a denial of his fundamental nature and was the cause of civilisational decline and the degradation of the spirit of man. Later, Nietzsche returned to the Dionysian idea of ecstasy or intoxication as an aesthetic state, relating this to an attempt to formulate a physiological reading of artistic reception.

“Concerning the psychology of the artist For art to be possible at all—that is to say, in order that an æsthetic mode of action and of observation may exist, a certain preliminary physiological state is indispensable ecstasy [or rapture]. This state of ecstasy must first have intensified the susceptibility of the whole machine otherwise, no art is possible. All kinds of ecstasy, however differently produced, have this power to create art, and above all the state dependent upon sexual excitement—this most venerable and primitive form of ecstasy. The same applies to that ecstasy which is the outcome of all great desires, all strong passions; the ecstasy of the feast, of the arena, of the act of bravery, of victory, of all extreme action; the ecstasy of cruelty; the ecstasy of destruction; the ecstasy following upon certain meteorological influences, as for instance that of spring-time, or upon the use of narcotics; and finally the ecstasy of will, that ecstasy which results from accumulated and surging will-power.”[vii] Heidegger summarises to result of aesthetic rapture: “Beauty is no longer objective, no longer an object. The aesthetic state is neither subjective nor objective. Both basic words of Nietzsche’s aesthetics, rapture and beauty, designate with an identical breadth the entire aesthetic state, what is opened up in it and what pervades it.”[viii]

Nietzsche was initially a supporter of Richard Wagner, seeing his operatic Gesamtkunstwerk (German: combined work of art) as the resurrection of noble forms that could be the rebirth Greek standards (as best seen in tragedy) via modern Germanic culture. The Gesamtkunstwerk seemed to fulfil Aristotle’s stipulations for ennobling tragic drama. Nietzsche did go on to retract that support and become a vociferous critic of Wagner. Nietzsche – who did not devote much time to aesthetics, in particular the visual arts, after his first book The Birth of Tragedy – was committed to the view of aesthetic response as intellectual and moral. He distained the Aesthetic Movement, describing “art for art’s sake” as a “variety of self-stupefaction”.[ix] However, he was at one with Whistler and Wilde on the matter of the taste of the masses. “The “masses” have never had a sense for three good things in art, for elegance, logic, and beauty – pulchrum est pacorum hominum [Latin: beauty is for the few]–; to say nothing of an even better thing, the grand style.”[x]

II.

The relative positions of morality and culture in mankind’s endless struggle with existential pain and strife become the heart of Nietzsche’s late writings, so we can see the early aesthetic concerns of Nietzsche as a precursor to his wider concern with the decline of humanity under the two burdens of rationalism and Christianity. Nietzsche saw humanism as an outgrowth of Christianity. “The time is coming when we shall have to pay for having been Christians for two thousand years: we are losing the firm footing which allowed us to live – for a long while we shall not know in what direction we are travelling. We are hurling ourselves headlong into the opposite valuations, with that degree of energy which could only have been engendered by man as an overvaluation of himself.”[xi]

Nietzsche rejected the Idealism of Hegel – and his metaphysics – opening the door to a Burkean physiological reading of aesthetics, while at the same time rejecting the materiality of the new Psychology school of aesthetics. Regarding the fact that Nietzsche was concerned to re-examine every social value in a critical manner (including Christianity and the humanist approach of taking man as the measure of all), it is worth including his comments on beauty from a late book Twight of the Idols (1889).

“Nothing is beautiful, except man alone: all aesthetics rests upon this naïveté, which is its first truth. Let us immediately add the second: nothing is ugly except the degenerating man – and with this the realm of aesthetic judgement is circumscribed. Physiologically, everything ugly weakens and saddens man. It reminds him of decay, danger, impotence; it actually deprives him of strength. One can measure the effect of the ugly with a dynamometer. Whenever main is depressed at all, he senses the proximity of something ‘ugly.’ His feeling of power, his will to power, his courage, his pride – all fall with the ugly and rise with the beautiful.”[xii]

Although Nietzsche’s direct engagement with aesthetics was relatively brief in his lifetime-published writing, he did comment on the position of the artist. We find some of aphorisms and notes on artists in The Will to Power (1901), a book which was compiled from unfinished manuscripts without the author’s direction and published posthumously, and which has been criticised as misleading. However, it is worth looking at a couple of quotes.

“The greatest crimes in psychology [include] [t]hat greatness in man should have been given the meaning of disinterestedness, self-sacrifice for another’s good, for other people; that even in the scientist and the artist, the elimination of the individual personality is presented as the cause of the greatest knowledge and ability.”[xiii]

So, Nietzsche here considers that complete engagement and expression of the creator is valuable and that the elimination of the radical subjectivity and personal involvement in the creative process (which he views as valuable and necessary), has diminished culture and science. In the same list of transgressive and deleterious acts by psychologists, Nietzsche includes the pathologisation of pain, suffering, passion and strong emotions, the cheapening of love and promotion of weakness. This was related to his belief that socialism – with its jealous distain for the exceptional individual – was a form of warfare against genius; socialism (guided by Christian “slave morality”) set up the poorest man as the spiritual standard for culture.[xiv]

“A capable artisan or scholar cuts a good figure if he have his pride in his art, and looks pleasantly and contentedly upon life. On the other hand, there is no sight more wretched than that of a cobbler or a schoolmaster who, with the air of a martyr, gives one to understand that he was really born for something better. There is nothing better than what is good!”[xv]

The artist becomes a paradigm of man liberated from humanism, scientism, socialism and Christianity, who can go on to re-establish the foundational values of society. Here is Heidegger on Nietzsche: “Art, thought in the broadest sense as the creative, constitutes the basic character of beings. Accordingly, art in the narrower sense is that activity in which creation emerges for itself and becomes most perspicuous; it is not merely one configuration of will to power among others but the supreme configuration. Will to power becomes genuinely visible in terms of art and as art. But will to power is the ground upon which all valuation in future will stand. It is the principle of the new valuation, as opposed to the prior one which was dominated by religion, morality, and philosophy. If will to power therefore finds its supreme configuration in art, the positing of the new relation of will to power must proceed from art.”[xvi]

We can give the final word to Nietzsche: “Art is the distinctive countermovement to nihilism.”[xvii]

III.

Regarding aesthetics, was Nietzsche a reactionary? If we define reactionary as “a position that rejects (a) the circumstances of the status quo, (b) the consensus social values of the period and (c) the apparent direction of social change, considering them deleterious to the wellbeing of a given group of people” then Nietzsche does seem to fit the definition. Certainly, he does not deprecate the entirety of Germanic culture of the day – see the exception of Wagner, at least early on – but he is critical of most modern culture because he sees it stemming from humanism, rationalism and Judeo-Christian ethics, which he rejects completely.

Some consider reactionaryism to be necessarily retrograde, involving the advocacy of the return to an earlier state. This has certain problems, not least the fact that as a course of action for the immediate future, return to an earlier state involves the dismantling and reversal of much of society’s structure and values, which seems more revolutionary that reactionary. Also, there are difficulties in that this position necessitates the return to a position from which the current (unsatisfactory) status quo developed. It is simply returning to an earlier stage of the progressive disease to which the reactionary objects. Returning to 1950 would not necessarily solve anything, as the social and economic situation of 1950 gave rise to that of 1970 and 2000 and so forth. The same applies to 1500 or 1500 BC. This second definition of reactionary has a quality of nostalgia (within living memory or derived indirectly), which is not necessary to the reactionary position. The reactionary position says, “Today is unacceptable and unsustainable; new values and leadership are required.” It may or may not recommend taking a previous era or place as a benchmark for a future society, but this is not necessary. All that is needed is for the reactionary to (a) reject the status quo and (b) propose an alternative, however definite or indefinite, remembered or invented that alternative may be. A person who condemns and rejects but has no ideas about potential alternatives is not a reactionary but is simply a critic, naysayer or dissident – although any reactionary must take on these auxiliary roles.

Does Nietzsche conform to the second definition, by including a call for society to return to an earlier state? The difficulty of including Nietzsche as a reactionary under the second definition is that Nietzsche’s historical model is both ancient and foreign. It would not be reasonable to suggest Nietzsche was recommending modern Germans become ancient Greeks, rather, he was advocating the embrace of the ways of thinking and acting that allowed the ancient Greeks to produce sophisticated cultural-religious events that allowed participants to satisfy their complex contradictory psychic needs. (Nietzsche is a conservative, seeing human nature as not socially constructed or perfectible.) Nietzsche was not arguing that the future lay in being (or even acting like) ancient Greeks, but in finding new ways of solving the needs of the eternal unchanging character of man, as the ancient tragedians had. Strictly speaking, he was not calling for a return, but calling for a radical realignment of principles to match those of the ancients. The correct interpretation seems to be that Nitezsche is not a reactionary, by this second definition.

This second definition seems to me to be wrong. The components of nostalgia and atavistic yearning are supplementary qualities for a reactionary, not prerequisites. The reactionary may not have in mind a specific historical model, may not think a return to that situation is feasible or may not have a feeling for history and consider such reflections on history to be unnecessary or distracting.

Nietzsche’s opposition to Christianity – both its basis and its outcomes – puts him against both materialism born of capitalism and rationalism from Socratic (and Enlightenment) thinking, but with no recourse to an established religious foundation, which might provide him with a moral basis for a rejuvenated society. Reactionaryism has inherent ambivalence towards Christianity, with many seeing Christianity as inevitably leading to the Enlightenment and its own deconstruction. For many reactionaries, Christianity is futile because it is an elaborate machine which (when adequately evolved) dismantles itself. Nietzsche had his own ideas on a moral framework – or at least encouraging and developing those individuals who would provide such a framework – but that is another subject.

Nietzsche’s aesthetics are framed in heroic terms and demand the veneration for the great figures that artists could be – as leaders, truth-tellers, path-finders or visionaries. He has little to say about processes of aesthetics (perception, memory, imagination) and chooses to discuss the functions and reception of culture and the character of artists. In this, he is thoroughly reactionary in his rejection of contemporary mores. When it comes to individualism in the wake of Romanticism and the Enlightenment, Nietzsche suggests hyper-individualisation through self-actualisation but in the service of society. This is exemplified in the actions of the artist leader as a vanguard figure.

This article draws upon part of the forthcoming course by Alexander Adams Foundations of Aesthetics: Advanced, available to purchase from

https://www.academic-agency.com/

[i] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1956, p. 21

[ii] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1956, p. 22

[iii] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1956, p. 24

[iv] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1956, p. 131

[v] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1872

[vi] Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, 1956, p. 126

[vii] Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 1911, p. 66

[viii] Martin Heidegger, David Farrell Krell (trans.), Nietzsche: Volume I, 1961, Routledge & Kegan, 1981, p. 123

[ix] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1933, p. 24

[x] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, quoted in Heidegger, 1981, p. 124

[xi] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1933, pp. 25

[xii] Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 1889, in Harrison, 2011, p. 786

[xiii] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1933, pp. 243-4

[xiv] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1933, p. 24

[xv] Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 1933, pp. 64-5

[xvi] Heidegger, 1981, p. 72

[xvii] Nietzsche, quoted in Heidegger, 1981, p. 73

Thank you for this essay.

Tragedy as I understand Nietzsche in Birth, is the Apollonian hero mocked by the Dionysian chorus of satyrs.

It’s weird that Nietzsche thought Humanism derived from Christianity. I thought Humanism was more geared to the human and Christianity to a supernatural order. I’ve never understood the idea that human rights derived from Christianity. When did Jesus talk about human rights?