My father’s library

A decade after my father's death, I looked at his books and understood grief and gratitude better.

Ten years after my father’s death, I opened the boxes I had spent a decade avoiding. When my father died in 2014, my sister and I inherited his book collection. Rather, we had our pick of the books. The large bookcase filled a wall; its contents comprised a witness to our father’s life and our family’s history, too copious to remove entirely. My sister made her selection of a very few volumes before me. I took a small collection of books, put them in several boxes and took them away; I did not unpack the boxes fully until last week.

To state that the boxes had been kept at several storage units, some of the time inaccessible to me, simply begs a further question. It does not explain why I allowed that to be so. In truth, I could not face opening the boxes. When I saw the books again, I was so overwhelmed by a wave of guilt, grief and inadequacy – and a fair amount of self-pity – that I subconsciously memorised the appearance of the boxes so that I would never accidentally open them again. So it remained for until I got married, last year. Prompted (firmly but sympathetically) by my wife, who thought my grief had lasted unnaturally long – and spurred on by the necessity of reducing my personal collection of books – I opened the boxes and the folder I had so long avoided.

The books that belonged to my father fell into different categories for me. Before I write about what I kept, I should mention the character of the books I skipped. There were the few books my sister took, ones on Bronze Age archaeology and barrows – a link to childhood visits to West Kennet Long Barrow, the White Horse of Uffington and Avebury stone henge. My aunt also took some books, related to their past. There were some notable absences that were not available. Our copy of The Hobbit had disintegrated and The Lord of the Rings had been ruined by water damage. A handful of cherished Penguins were too fragile to be re-read, paper edges almost tobacco brown and friable.

Aside from those, there were tranches of John Fowles, Kingsley Amis, Len Deighton, John le Carré which held no interest. Scattered volumes of science fiction likewise didn’t catch my attention. There were books which spoke of the social and political issues of the 1960s to 1980s, such as hedgerow foods, mushroom picking, the Campaign for Real Ale, wine tasting and issues of magazines relating to the Rare Breeds Trust. All of these formed a cross-section of the post-hippy liberal middle-class milieu of the time. There were some books on cars, complementing a run of Motor Sport monthly, stacked in a box in the attic. We’d read the books, talked cars, watched televised grand prix and visited race meetings at Oulton Park together. His loss had left me with no one in my life with whom to share thoughts on the subject, so I passed on those few books. There were some subjects we had never had in common. His books on sailing meant nothing to me, emotionally.

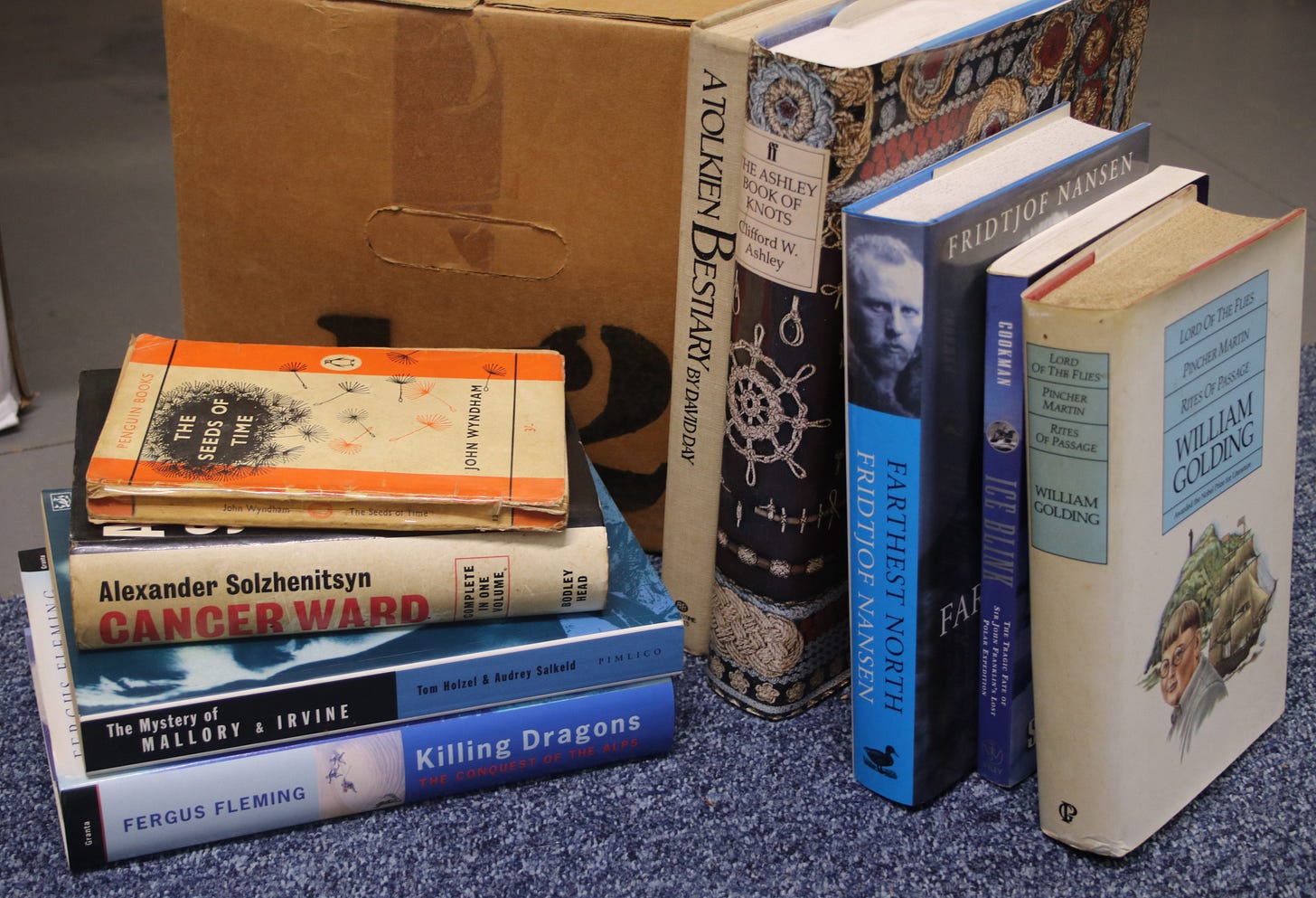

Some books that I took were ones that I read multiple times and cared about. Kafka’s Metamorphosis and The Trial (Penguin paperback editions), John Christopher’s Death of Grass, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books and John Wyndham’s core corpus (Penguin again) formed my view of the world and were books I have re-read many times. There were others we had read and discussed at length. Many of these I had bought as presents. The subjects were mountaineering and polar exploration, about which we compared notes.

Bernard Noël’s Magritte (Bonfini Press, 1977, hardback) was a book that shaped my world and inspired me to be an artist, but that was the only book on art we had in the house – a very curious fact. A picture book that left a powerful impression was Say Goodbye You May Never See Them Again (Jonathan Cape, 1974, hardback). It was not strictly an art monograph but a series of captions written by Arnold Wesker to accompany the paintings of John Allin. Allin’s naïve paintings of East End street scenes, with laboriously painted brick walls and flat style, seemed to me definitively connected to Magritte’s. I spent hours poring over the books, trying to decode the magic, memorising the images and daydreaming.

There were authors my father felt proprietorial towards but to which I had only a second-hand association. These included P.G. Wodehouse and Raymond Chandler, both of whom were (as my father was) Old Alleynians (alumni of Dulwich College, London). I kept nice editions of the Wodehouses but passed on the Chandlers.

Books which fell into both these latter categories were those about Sir Ernest Shackleton, another Old Alleynian. My father talked about the James Caird, the small whaling boat (now located in his old school), in which Shackleton sailed from Elephant Island to South Georgia – a journey of epic endurance, huge courage and remarkable skill, which epitomises in my imagination the heights of heroism. I made a private pilgrimage to the small boat, now repainted and resting on a sea-rounded stones in glazed hall at Dulwich College. My father and I talked endlessly about Shackleton, Nansen, Scott, Franklin and so on.

Conversely, there were books that were barely my father’s – his by inheritance alone. His father (my grandfather Leslie, whom we called “Grandpop”) bought new copies of Folio Society editions of classics. These were passed on to our family on his death in 2008, but (aside from the Wodehouses) I think our family barely touched Grandpop’s library. These were the only books that were worth anything monetarily, although I kept them because they were handsome and evergreen in content.

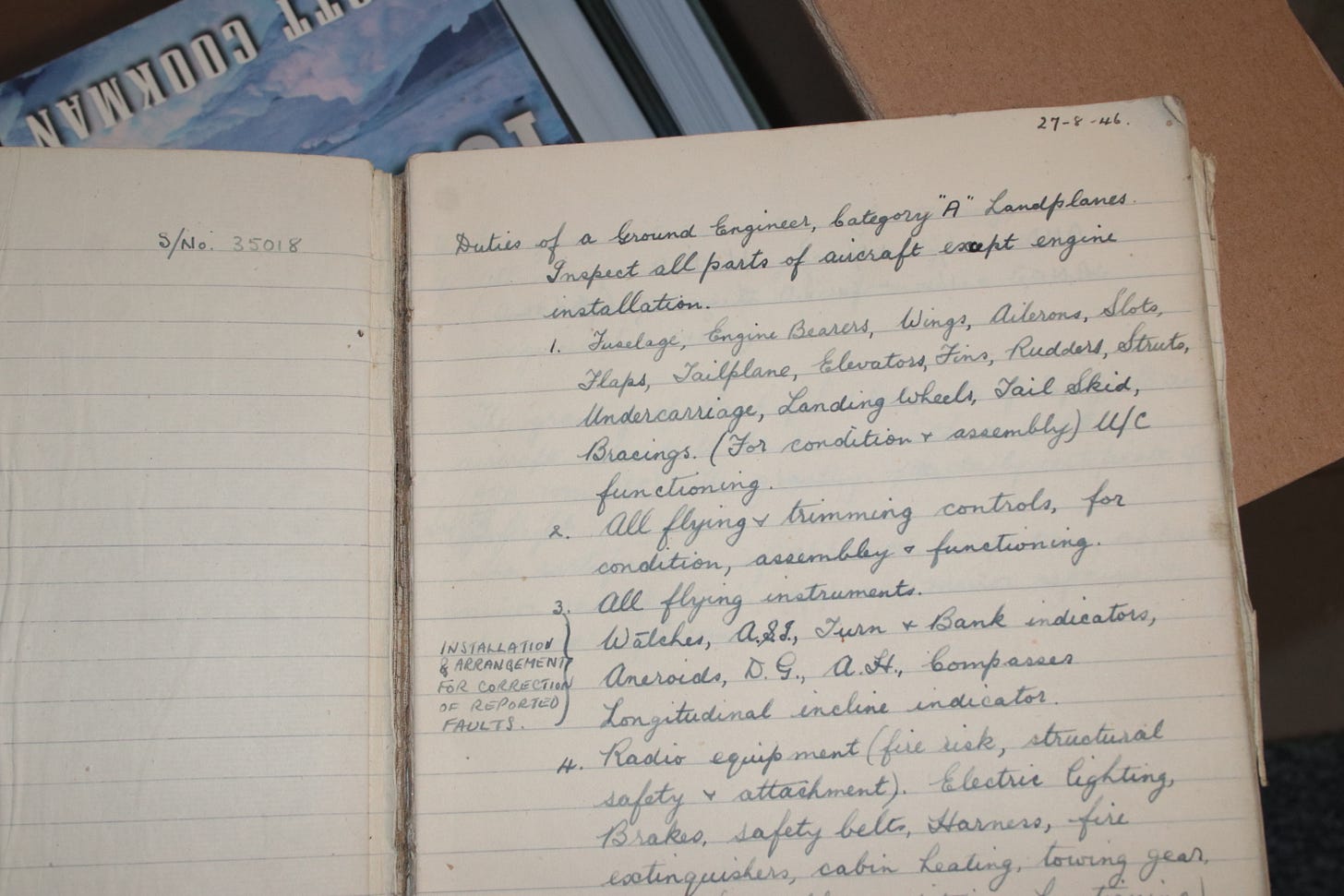

More personal were books of biographical significance. I found a notebook of Grandpop’s detailing his duties as a member of BOAC’s ground crew in Croydon Airport. Dated 1946, it enumerated qualities of alloys, checklists of problems and included wiring diagrams. The job was one he took after being released from war duty as an aeronautical engineer. A manual on aeronautical mechanics came from the same year and is stamped property of BOAC. Even older was a fragile notebook containing entries (in an inelegant hand) about printer’s marks and rules for typesetting. It is disappointingly undated, but must be from his brief time as an apprentice print compositor, when he must have been around 16, from 1929 for so.

Opening up the cardboard boxes and taking out the books, I pondered on what it means for men to inherit their father’s legacies. It is not a straightforward thing to receive a gift that is both of value and costs money to keep, that is a small material benefit and an emotional burden – if one takes it that way. Of course, one could be purely glad or utterly indifferent, giving away or selling the inheritance, causing it to leave no trace in one’s life. But I suspect that most men weigh up carefully what they can take on and do so with mixed emotions about the responsibilities entailed.

Last week when I viewed books, I felt curiosity, affection, sadness but at a reasonable level; the newly lowered intensity was evident to me. Even a few years earlier I couldn’t have stood to view them. Something had changed. Slowly, I had overcome my perception of my father and grandfather. These men who had flown or designed aircraft and had (in my mind’s eye) taken on the mantle of fighter aces. It was an absurd inflation but no more preposterous than matching the seemingly unattainable heights of their actual achievements of owning homes, buying cars, saving money and raising families, which of all seemed beyond me. While the three of us shared an interest in the mechanical, the questing and the adventurous, they had actual experience of these fields, while I had merely a vicarious enjoyment. I did not have any achievements, either remarkable or mundane, that compared with what they had done. Only after the milestones marriage and setting up my first real home, did I feel capable of looking at their legacies.

So why (other than due to a sense of inadequacy) did I previously have such an extreme response to the books? For ten years I had been unable to take proper ownership of the books and had been unwilling to dispose of them, caught in an oscillation between anguish and denial. This might have been understandable had my father died protecting his books or if he had been executed for writing them, but he hadn’t. It was a disproportionate view that betrayed a lack of self-insight. What I realised when I emptied the boxes was that the paralysis of stasis (the double-barrelled incapacity-regret response) had frozen emotions rather than permitting the lessening of emotional charge that comes with grief’s development and the necessary detachment from my father. By allowing myself to view the books as books, not as symbols of loss, I could finally treat the books as my father had intended: objects that had been part of fond memories and bore witness to shared interests.

Considering the books in the proper manner (no longer like unstable bars of gelignite) was a step to becoming my own man – someone beyond son of Adrian, grandson of Leslie – a man who could master his emotions and care for an inheritance. I had made no progress for seven years following my father’s death. It was only after meeting my future wife and (at first unwillingly) discussing with her my difficulty dealing with the books that I understood that overcoming grief did not mean dishonouring nor forgetting. Thinking of my father’s books as an inheritance – rather than a duty or (in some figurative sense) a measuring stick – was the appropriate way to treat them and understand my role.

I shall never need Aeroplane Performance Theory for Pilots and Engineers; indeed, not even an aeronautical engineer would need this book nowadays. Perhaps it will one day be passed on to a (as-yet-unborn) child as a family keepsake, with the information that Grandpop worked in that field. Maybe not. I shall never read cover to cover The Ashley Book of Knots, but when I see it I remember my father unwrapping that book on Christmas Day, complete with two short lengths of rope, and recall his pleasure at the gift. Now that book knots me and my father together forever, with a link not so much of loss but more of love. I was finally ready to have his (our) books on my shelves and in my life.

In memory of Adrian Adams (1944-2014)

Physical books are pieces of history. I collect old books; many have the names of previous owners written on the inside pages; little comments in the margins or underscoring of particular passages and comments felt to be pertinent. I’ll never know those people but I feel like I know something of them…

I inherited a lot of books from my own father on his passing. Patrick O’Brian (the Aubrey/Maturin ‘Master and Commander books), Bernard Cornwell (The Last Kingdom books), Robert Graves (I, Claudius) among other historical based books. But also Ian Fleming (the Bond books), Stephen King, Gerald Seymour and Harold Robbins- a pulp fiction writer who was huge in the 60’s/70’s. Biographies of the famous and infamous, And atlases and travel books - yet my father hardly ever left Northern Ireland. I guess that speaks volumes.

A mixed bag of high and low brow books I suppose, but they convey a sense of a life. I should let go of some of these books but I can’t. Thanks so much for sharing your dad’s books with us - deeply moving to read.

Excellent and very moving piece. I have had similar experiences with my father’s books. A lot of Faulkner.