Magic or explanation in art

A new book about Francis Bacon's paintings, raises the question "Does explaining art remove its magic?"

During his lifetime, British painter Francis Bacon (1909-1992) kept private the photographs that he used as inspirations for his powerful paintings of the human figure and animals. Preferring not to give precise sources or explain his painting process, Bacon instead offered his paintings without discussion. Even his titles (“Study of a Figure”, “Seated Figure”, “Dog”) revealed little. Since his death, the discovery of thousands of photographs from books, newspapers and other sources have been studied by art historians.

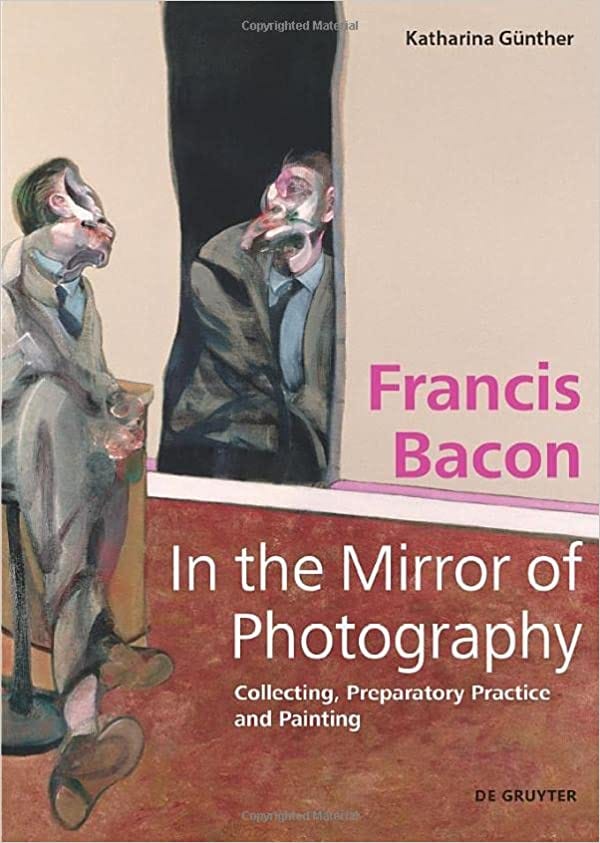

Art historian Katharina Günther goes a good way to proving her opening hypothesis in Francis Bacon: In the Mirror of Photography. Collecting, Preparatory Practice and Painting (De Gruyter, Berlin, 2022, 445pp, fully illus., hardback, £52, ISBN: 978 3110 720 624) that “Bacon’s iconography stems from the pre-existing, mostly lens-based imagery he collected in his studios for this purpose […] [This is] a well-rehearsed, deliberate, and consistent appropriation practice. In fact, it may well be that all his paintings were based on photographic material, a claim which has been made in the past, without, however, underpinning it with any data. Second, the working process can be deciphered by carefully investigating Bacon’s working documents and environments, through comparative analysis of the source item and the finished canvas, and by tracing the appropriation process from one to the other. […] We may then detect and interpret recurring patterns and methodologies, providing us with an in-depth insight into Bacon’s creative process, which will help us better understand his work.”(p. 10)

Her book examines the source photographs found in Bacon’s studio and links them to specific paintings, providing liberal illustration and discussion. The book (which is pleasurable, thoughtful and a compliment to the reader’s intelligence) definitely broadens and deepens our understanding of the art, but it may not benefit the art or our experience of it as art. Understanding and appreciating are not necessarily synonymous. Consider the magic trick. If we know the mechanical devices, sleights of hand, misdirection, showmanship and other elements deployed to fool us, we certainly know more about the trick, but the magic – what we value in the magic trick – is gone. Experiencing the sensation of wonder is why we love magic – that brief feeling of shock and surprise accompanied by incomprehension that allows us to unlock something childlike and delightful within us. Even if we understand on an essential level that we are being deceived, we briefly believe in powers beyond knowing. Magic startles us from our habitual assumptions about the world and ourselves. Aesthetic philosophers have sometimes compared the transformative experience of encountering art or nature of amazing beauty or novelty as akin to a religious experience. We might be able to determine a particular pattern of synaptic stimulation to the experience of ecstasy, but that does not explain the experience’s significance. Magic, art, sex and religious ecstasy all open our minds to a rare state of pleasure, one that stands to some degree antipathetic to mere knowing.

In the work of Günther and other art historians, there is an obvious struggle. Let us take the study of Bacon’s photographic sources as our example. On the one hand, all historians and critics who have long considered the matter conclude that Bacon was deeply influenced by photographs, not least on the authority of Bacon’s interview statements on the matter. On the other hand, Bacon deprecated photography as an art form and refused to be specific about how he used photography. Historians have also been reluctant to pin down too closely paintings to exact sources, perhaps finding the process reductive and demeaning. So, the paradoxical situation has developed that everyone acknowledges that photography was important to Bacon but few want to commit to writing about exact links, sometimes talking about the atmosphere of the studio and the general stimulation produced by such a working environment. During the artist’s lifetime, his personal disapproval of such discussions (he never allowed anyone to examine the studio material during his lifetime) directed discussion; since his death, this field has been opened but (as Günther notes) few have stepped in and drawn specific links.

Bacon was, quite understandably, protective of his creative process. He must have been concerned that in an age of professional art historians, museum archives, recorded interviews and extensive publication, the story of the making of art would reduce the mysterious power of his paintings. It was the paintings he chose to make his final statements, unqualified by sketches or documentation of preparatory stages. In such circumstances, Bacon’s preference to conceal his exact working methods is understandable and compatible with his intention to allow his paintings to live and die by the amount (and nature) of appreciation they received as art. Despite Günther’s claim, “[T]his is the line of enquiry that should be pursued – not to diminish Bacon’s art but to highlight a highly creative and unique working process”(p. 35), it is difficult to see such scrutiny as other than a dilution. Once informed, we cannot approach a Bacon painting innocent of its origins and open to its startling novelty and raw emotional force. We become conditioned to see the experience of that painting as the culmination of a process of image acquisition, adaptation and translocation. We not so naïve as to consider a painting to be conceived and executed ex nihilo, but to have our experience of the art so altered by considerations outside of the meeting an observing subject and observed object inevitably leads to a lessening of power – even if that power were actually illusory, self-serving and a manifestation of the aesthetics of art as pure, detached, disinterested communion.

The degree to which artists protect the secrecy of their working methods is a matter of debate. In an age when so much more is recordable and archive culture is more developed (and monetised), the artist has to consider how many traces to leave behind. Does one keep or dispose of sketches and diagrams? Does one number or date working material? Does one keep secret photographs? If these photographs are digital only, how secure is their future without a printed version? Does one keep a list of books consulted or seek to consign to oblivion the reading background of the creator? Would anyone viewing the finished art consider that art finished if that observer had access to all of the sketches, notes and initial stages of that finished art? Such material turns the culminating painting into part of a process – a stage in a narrative.

I had this discussion with an art historian friend of mine, with me taking the role of an artist keen to preserve the mystery of my finished art, emphasising the argument that expansion of art parameters to include preparatory material was often regrettable. I suggested that (specifically in the case of Bacon’s art) presentation and discussion of source material inevitably diminished the power of the art because of this “narrativizing” effect of contextualisation. His argument was that addition of extra information and material was not diminution (or subtraction) of the status of the art and that it was the duty of historians, collectors and acquaintances of the artist to preserve as much material, documentation and recollections as possible for the benefit of future scholars and biographers. I see his point but I also see mine. Yes, it is a benefit for the historian, biographer and other expositors of art to have as much information and as many sources and stages preserved. But also, yes, if one wants to appreciate the power of art, nothing is needed other than the work itself. Indeed, part of the force (dare I say, magical force?) of cave painting or Cycladic sculpture is that pervasive and impenetrable ignorance we have about the working conditions, motifs and ideas of the original makers and audience of this art.

As both an artist and an art critic/historian, I see this dilemma acutely. What I decide with regard to preserving my own preparatory materials and elucidating the process of making, I have not decided. As an artist, I think that silence can be infinitely more expressive than any word or sign, which limits both listener and speaker. Yet, as a writer of books such as “Degas” (Prestel, 2022) and “Magritte” (Prestel, 2022) and a forthcoming volume, I eagerly consume all the sources I can find about my subjects. There may be no easy answer, perhaps there can be no answer at all, but it seems necessary to consider this dilemma.

Francis Bacons pictures make me vomit. We live in an age in which all things deviant, rotten and ill are alleviated to the level of art. Hence, art turned into a piece of shit.