Is a painting ever finished?

Some artists consider their works unfinished (only abandoned), to be taken up again later. Some reserve the right to destroy it.

The answer to the question “When is a painting finished?” is fairly plain: when it leaves the artist’s studio. Once a picture has been handed over to a gallery, agent or collector, it is in the protection of another party, even though it may continue to be (temporarily) property of the artist. At that point it is out of the artist’s oversight and no longer in proximity of materials used to make changes. Paintings consigned on sale-or-return terms are generally returned to the artist after exhibition. Paintings left with artists over a long period are sometimes subject to revision, occasionally due to dissatisfaction or better ideas. Formal portraits have been altered because the sitter has aged or the clothes have become outdated. Velázquez’s earliest royal portraits are lost under later repainting, which changed poses and made clothing more fashionable. Some artists have had difficulty leaving paintings alone. Both Monet and Degas were notorious for returning to revise or completely rework pictures – much to the dismay of owners.

In printmaking there is often a first state of marked plate or stone, which is a preliminary test. In those cases it is usually understood that this is trial, with areas left blank or only outlined. This is an interim stage rather than a finished picture being reworked. The nature of oil painting is that the first stage is left under the later ones and remains inaccessible except through x-ray or spectrographic analysis which is incomplete and inaccurate to the actual appearance of that stage. What if we could see the original paintings before they had been changed and therefore be able to gauge the extent and relative success of the changes in comparison?

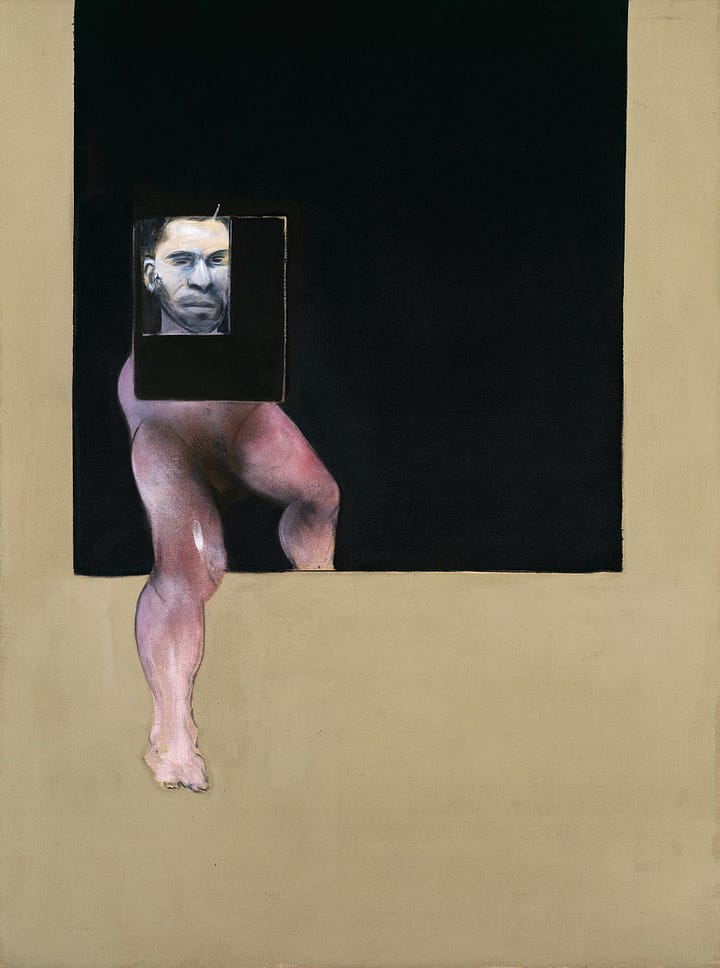

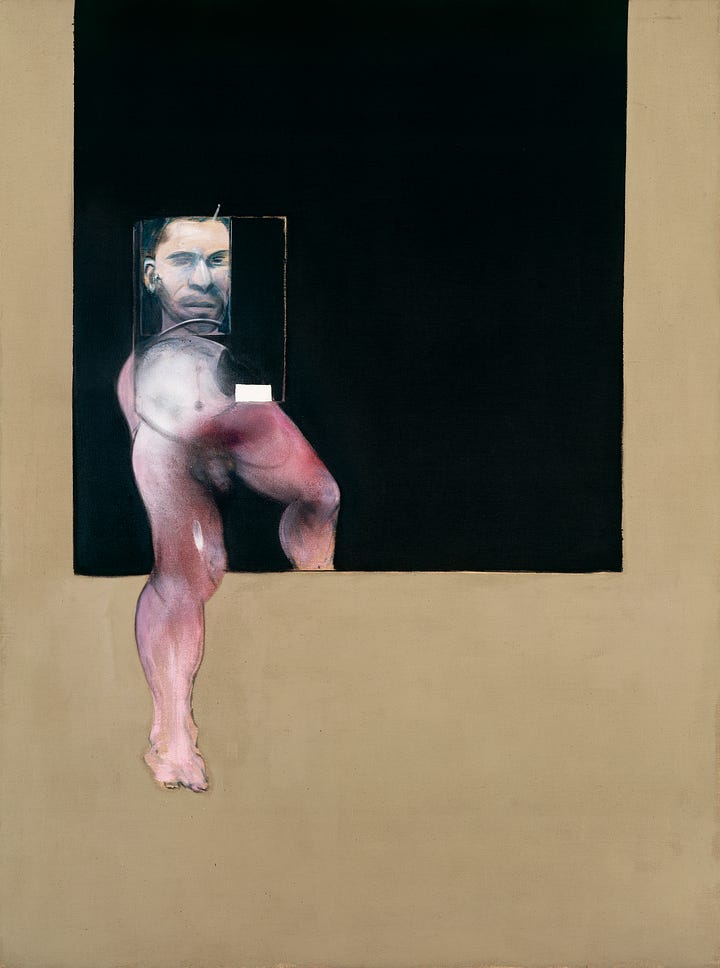

We have long had photographs of unfinished paintings. Since the invention of photography we have had records of paintings in progress. There are sequential images of art by many artists, including Matisse, most notably La Grande Nue – Pink Nude (1925). Clouzot’s film The Mystery of Picasso (1956) showed Picasso at work on various drawings and paintings; we saw them develop, but in all sequences the art was never finished until the final state. The paintings in a new book Francis Bacon: Revisions (Martin Harrison, The Estate of Francis Bacon Publishing, 2024) are ones that Bacon considered complete and had consigned to his dealer before changing his mind and recalling them. As these paintings were photographed when they first arrived and in their revised last state, we can view what Bacon considered definitive only see him change his mind and make alterations, revealing precisely what dissatisfied him about an image he had considered good enough to enter the public arena. To those of us who have followed Bacon’s (relatively limited and thoroughly published) oeuvre, this is fascinating insight. I cannot think of a comparative case. It is rare to see an artist’s work through his own eyes.

That Bacon’s revisions are recorded is due to two causes. The first was practical and the second was tactical. From 1961 until his death, Bacon inhabited a small mews house in Kensington. The limited space meant that Bacon could not store many canvases (finished, unfinished or blank), so finished paintings were (even while wet) given directly to his dealer Marlborough Gallery. Art was photographed when it arrived at Marlborough’s London depot, hence there are high-quality contemporaneous colour images of the paintings. (Compliments must be paid to the technicians who adjusted gravely faded colour photographs and managed to make them match the true colours, based on new highly accurate digital photographs of the paintings today.) Bacon could have hired a storage company to keep paintings independently but for whatever reason he chose not to.

Marlborough knew that it was to their advantage to keep the canvases out of Bacon’s studio, as he had a tendency (alarming to any dealer) to work a painting until it was spoiled and subsequently destroy it. When Bacon joined Marlborough Gallery (in 1958) he was sending pieces to the gallery, probably in to reduce his destruction rate. In an interview he admitted his weakness. “I sometimes let paintings out too soon because I find that if they are in the studio I go on fiddling with them.”[i] Considering how the paintings in their initial state were both acceptable, creditable and valuable, Bacon’s determination to get a picture right is a worthy and costly position for him to have taken. One can imagine his dealer’s exasperation at the painter’s fidelity to his standards.

Revisions is effectively a whole unseen body of work by one the last century’s most important painters. Of the 584 surviving paintings, almost 100 are known to have been revised, through painting or cutting down or were moved into or out of a triptych or diptych. Sometimes panels were completely replaced. Due to the artist’s preference to work on raw linen, after about 1950 he never reused an abandoned canvas in totality. That is, although he might radically alter it, he would never put a wholly fresh composition over an old painting. Revisions contains a few paintings that were reworked then later destroyed.

That Bacon changed his mind so often – and exactly how often – is interesting. Bacon always presented himself as unmoved by criticism. This was part of a show of being detached from the art world, movements and the desire to court approval (even that of the elite with educated refined sensibilities) but it was clearly not the whole picture. If one goes to his interviews, we find him speaking admiringly of the transcript of the edited drafts of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). Bacon declared that he wished that he had a partnership where a fellow artist could critique his work in progress so that he might gain from another’s perspective, as Eliot had with Ezra Pound. It is on record that he did take notice of comments by artists Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud, critic David Sylvester and gallery manager Valerie Beston.

Beston’s work diary contains useful data about when paintings by Bacon were collected, returned, adjusted and destroyed. The pair discussed the pictures as they were finished and Bacon would sometimes voice doubts regarding pictures. Beston’s responses did influence his thinking, although their opinions differed. She was dismayed when handsome pictures were altered or destroyed. The diaries are quoted liberally and the dates form the basis for the deductions in Revisions.

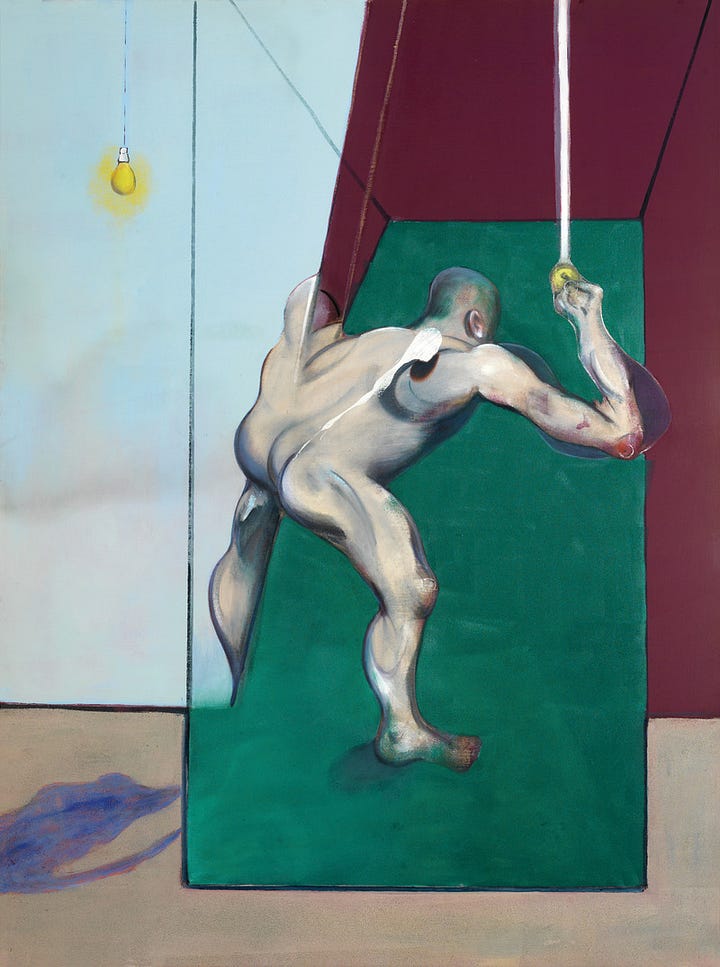

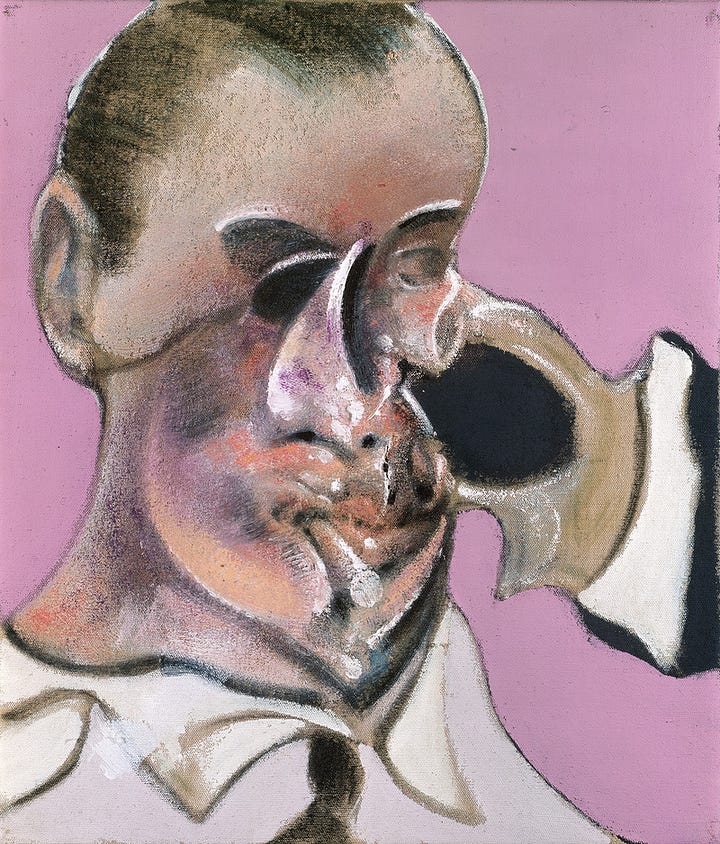

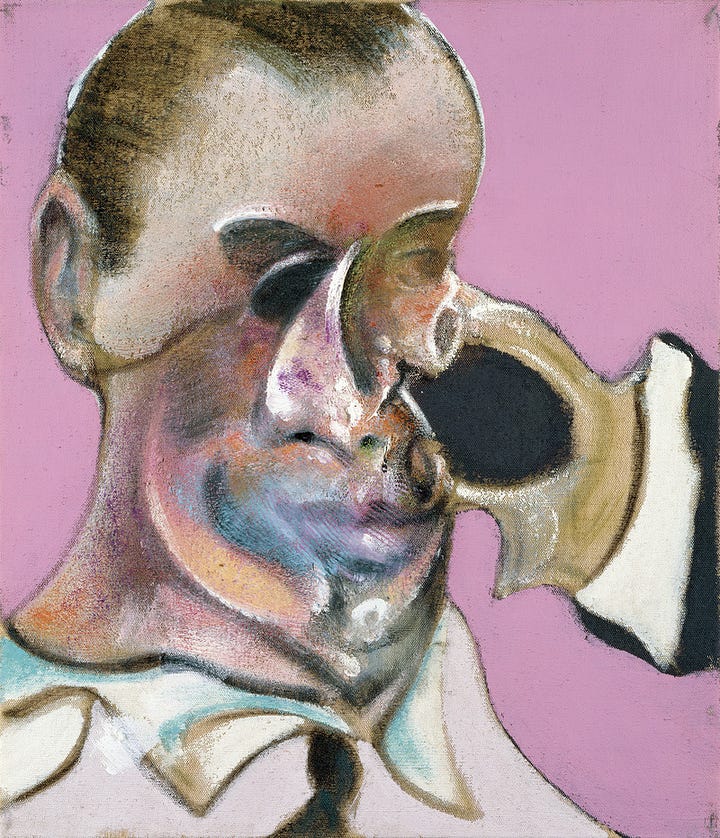

The fact that revision was possible is also relevant. The general perception was that Bacon’s technique was irreversible, but there were times when Bacon could make changes as delicately as a conservator expunging a distracting flaw. In a 1969 portrait the artist removed a cigarette in the subject’s mouth. In another portrait he removed a circular blot, having adjudged it unnecessary. Elsewhere, Bacon carefully blended colours so that he could remove other elements, such as shadows. In two male nudes of 1988-9, Bacon simplified the backgrounds and removed room armatures. Bacon clearly wanted to reduce distractions and par things back to an elegantly crisp concision.

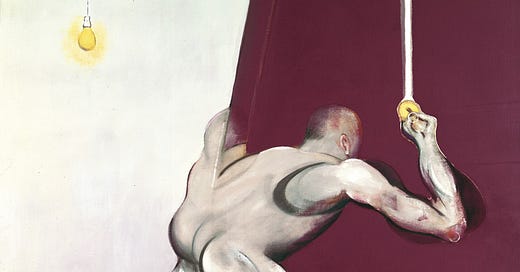

A 1959 painting was rescued by being almost totally repainted. A rather crude profile figure was turned into a man-woman combined double figure and given a startling mouth akin to a De Kooning Woman. Study from the Human Body (Man Turning on Light) (1973) was made more complex by the addition of a green rhomboid carpet/staircase, which opened new spatial implications. Others featured a change of colour, most often of the background but sometimes of the figures. There are sections on instances of new separate versions of paintings and single canvases being expanded into triptychs. In one case, a late triptych was split up only to be reunited.

Commercial imperatives affected the fate of pictures. Even in the later 1960s, when Bacon was established as a commercially viable artist, his large triptychs were difficult to place due to their size and price. More than once triptychs were reduced to diptychs or split into single paintings by the gallery, with Bacon’s approval, in order to sell them. Some of the paintings had public lives before the artist changed his mind. Triptych, May-June 1974 had a recumbent figure in the foreground of the centre panel. The set was exhibited three times and published before Bacon overpainted this presence in 1977.

The fact that this painting had been exhibited and published did not restrain Bacon from altering it, in much the same was Monet, Degas and Renoir saw no ethical or legal boundary as an impediment to making corrections. The difference was that Bacon (or his gallery) still owned the painting in question, whereas owners of Degas’s paintings were hesitant about allowing him access to his pictures for fear of an appearance altering revision. However, Bacon felt a similar power. When Bacon suggested that he repaint parts of his Painting (1946) in order to make it more stable, MoMA (the owner) politely declined this offer. When some collectors came to get paintings from his studio, they arrived only for Bacon to regretfully show them the tattered remnants. He had destroyed the canvas and would return the payment. Less provocatively (but more spectacularly), he would buy paintings by him that he considered failures and stamp them to wreckage on the street outside the dealer’s.

Clearly, Bacon considered his paintings – many titled “Study for” – existed within a continuum of the provisionally finished. He considered it within his moral rights to destroy a picture, no matter how much of a public life it had already lived. That he had such an imperious attitude (quite correctly) is expected and heartening. Art made by a creator with such sureness of ability allied to seriousness of purpose is a rarity. Whether one likes Bacon’s art is irrelevant. One can be appalled by his art and also find it truthful and compelling. Bacon was gambling for high stakes and so he could not afford for second-rate efforts to escape his knife, hence the ruthlessness of his decisions regarding revisions and destruction. Consequently, there are very few absolute duds in Bacon’s oeuvre.

Despite the appearance of impetuosity (in the figure) and also fixedness (in the setting) in Bacon’s mature canvases, his paintings were neither impetuous nor fixed. That we believed these illusions is due to both our impression of the style and the critical narrative established by the artist’s public statements. That Bacon fostered this situation – and also corrected it occasionally in interviews – is instructive. He knew that the magical spell of art that seemed unpremeditated but somehow inevitable is a powerful attribute that we assign to only the highest order of culture, especially relating to visual fine art. That this was achieved through canny balance should be no surprise to any close observers. The means by which he did so is documented in these photographs that capture his critical intelligence at work. This publication gives us a chance to see a great artist at work in a way that is unique.

[i] Quoted p. 32

The work in progress. I imagine it must be part of the inner torture of the artist - when to stop and walk away from a canvas or sculpture? When is it complete? The Swiss painter and sculpture Alberto Giacometti painted over his works again and again - not just because he was short of canvases (as Van Gogh, Modigliani and others were at times), but because he was endlessly dissatisfied with his work. He famously cursed and lamented whilst painting! The creative process was a source of constant pain for him.

I recall reading, a couple of years’ ago, that Vermeer’s ‘Girl Reading A Painting At An Open Window’ was found to have a naked Cupid that had been painted over - presumably Cupid got cancelled for some reason way back when, but is enjoying a new lease of life now. Of course, some of the figures in Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgement’ were deemed obscene and his pupil Daniel de Volterra was tasked with covering up their private parts. It seems fitting that paintings sometimes have a life of their own and carry their own secrets within the canvas.

👍 great