"I am a Cell of One"

The archetypes of criminal and artist are intertwined. Bravery, recklessness and egotism drive hero-villains, who fascinate us and embody the man-of-action.

In my novel The Naked Spur, we encounter a protagonist who is freeing himself from the world. He leaves the gallery scene, he detaches himself from friends, he cuts himself off from the world gradually, talking to fewer people each day. He becomes a hermit and a recluse, who cannot bear to see people functioning, earning a living, enjoying life, even as his tentative yearning for intimacy is cut off and his aspirations of making art that will shake the world dwindle to naught. Although we do not see it directly in the novel, that character (named “A.”) is the product of elite training. He studied at the best fine-art university department in the world. He rubbed shoulders with future stars of the art world; his tutors were rich and lauded. A. had every right to expect that if he was original and determined, he could sit at the high table beside them. He believed in the art world and the framework of meritocracy laid to his generation of future top-tier artists. The Naked Spur is the documentation of his decline into isolation, poverty and desperation due to his clinging to the story he was told as a young artist. The story of his brutal education and his inevitable extinction.

I recently re-read B.S. Johnson’s novel Christie Malry’s Double-Entry (1973). It is the story of a young accountant in London who becomes disaffected by his experience of life. He resents the boredom of his routine and begins to fixate on injustice. He sees low-character individuals around him benefitting from the system and the talented poor missing out on opportunities due to poverty, lack of education and systemic class prejudice. Growing ever more alienated by a system that seems designed to perpetuate unfair and unjust outcomes – locked in place by corruption, indifference and snobbery – Malry begins to calculate recompenses. When he is inconvenienced by the placement of a wall, he scratches it. When a colleague angers him, he destroys a business letter which puts his colleague in an unfavourable situation. He starts to write a list of entries of debits (injustices, annoyances, injuries) against corresponding credits (discomforting, disrupting, sabotaging). Malry becomes a rebel and then, as things escalate, a terrorist. His campaign culminates in an act of mass murder.

In one internal monologue, Malry declares, “I am a cell of one”. He understands himself as a isolated man, a hero (in his eyes) acting to wreak revenge for those too weak, stupid or afraid to act themselves. Malry is a “lone wolf” without affiliation, much less the aid of any fellow travellers. I was struck by the parallels between Malry and A. Both have potential. They have been compliant individuals and have sought to follow the systems they are raised within. They are not natural rebels. In some ways they are conformists who become deformed by the disillusionment they experience. They are not altruistic and act mainly to satisfy their emotional needs – in Malry’s case by imposing his morality on wrongdoers, in A.’s case by attempting to become a successful artist. They gradually change from being passive to active, responding to circumstances by becoming more stubborn and extreme.

In The Naked Spur we see A.’s activities trying to set up a scheme that will allow him to operate as an anonymous artist (intending to make a living by selling nude paintings) intercut with news reports on the killings of the Beltway Killer, active in October 2002. Although it was not known until the arrest, the killer was actually a pair of men working together on their scheme to terrorise Washington DC, Maryland and Virginia with a series of random shootings in public. We see A.’s collaboration with Mack (complete with games of subterfuge, media manipulation and misleading rumours) as an unconscious parallel to the criminal acts of the Beltway Killer pair.

The Vir Heroicus Sublimis (Latin: man heroic and sublime) is embodied today in two figures: the artist and the criminal. Both are isolated, driven by ego and the overweening drive to impose their will on the world. They do not always want to claim credit publicly but they savour their triumphs. They are ultimately selfish and self-motivated. They seek to evade limitations imposed by society on the common man by acts of exceptional ability. They are brave, arrogant, intelligent, disagreeable, driven. Fundamentally unreasonable, they take risks at a level that most consider unwise, irrational, even insane. They operate outside the constraints of taste and decency; they scorn acceptance and mediocrity. Indeed, they prefer death to the dishonour of normality. They would rather fail than conform. Ultimately self-destructive, they would rather have their mental schema collapse and become discredited than see it compromised by the influence of society.

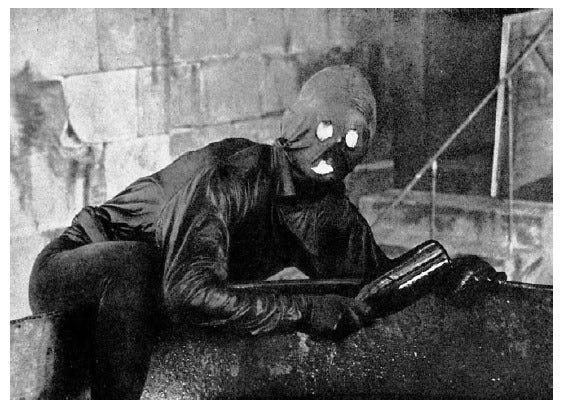

The Surrealists saw the analogy between the revolutionary artist and the criminal. Magritte had an affinity with the sinister character Fantomas, the supernatural anti-hero who appeared in detective stories and films, and whom he depicted in his art on a few occasions. Magritte clearly identified with the outlaw who defied both the laws of society and of nature.

In Nietzsche’s conception, the artist is one archetype of the vanguard, who is entrusted as lawgiver and pathfinder. (The other is the warrior.) The pioneer artist is cursed to be misunderstood, like the prophet Zarathustra, who isolates himself on the mountaintop. Both are mocked and shunned. We can immediately see this exemplified in the career of Van Gogh, accursed genius who seeks solace among tragic prostitutes and unclean miners, only to be rejected by even them. He is berated by his father as a heretic when he preaches the social gospel of Christ and is subsequently cast out of his Church. Van Gogh pursues his calling to create a new art and bind together bands of brother-artists with a religious fervour, expecting nothing but lifetime scorn followed by posthumous love. Van Gogh’s self-written story is of a masochistic criminal-artist, living on the edge, courting rejection as much as seeking acceptance, unshakeable in his ecstatic egotism.

There is veneration for the criminal and artist at the highest level (and a commensurate contempt for them at their lower levels of ability) because of their bravery and egotism. They engender a widespread lingering fascination with both their actions and their pathology, with a concentration on explaining their abnormalities through psychologising and sociological reading of their circumstances. Although one might assume that this fascination with the exceptionality of the artist and the criminal has two fixed moral polarities – we want to understand the brilliant artist because we need to identify his qualities and emulate his type of achievements and we want to understand the depraved criminal because we need to identify his morbidities and prevent his type of lawbreaking – we often find this is a grey area, where the criminal is lionised and the artist demonised. For every patrician art critic praising the radical artist, we have a scandalised conservative decrying the abasement of beauty and convention that this overrated shyster perpetrated. For every forensic psychologist alarmed at the imbalance of a killer, we have a hybristophiliac woman writing love letters to the gaoled murderer. The clarity of values and responses is not as clear as one might suppose or hope.

As that comment suggests, I do not say we should unthinkingly venerate either the artist or the criminal. The artist may be the way-finder for an ideological faction that is devasting to us. Through neophilia, counter-elite backing and zealous passion, the artist may open horrors and be an agent for chaos that destroys what we love and need. He may be the tool for those seeking to undermine a culture. I do not see creativity as valuable in itself and I do not see the artist as above common morals. The unfortunate fact is that for the artist to be the exceptional individual, he breaks conventions and laws and must have the determination to fight his cause, although that will cause suffering to others and himself.

Unlike Malry, A. is part of a disenfranchised elite, a surplus who is unable to compete because of the overproduction of the elite-tier artists through an art-education system that is the victim of its own success and was in the process of a down cycle, marked by excess of prospective professional artists and the decline in quality of artists and art. The danger of the overproduction of the elite is that there arises a critical mass of disaffected, intelligent, qualified, motivated individuals who cannot gain entry into a sufficiently high level of the system. This forms into an organised minority (as per Mosca) which co-ordinates and agitates and – if a cycle of entry and release is not made available – foments not only discontent but revolt. This is a counter elite. We see such an elite forming today. A. was part of the Generation X elite trained in the early/mid-1990s, many of whom (in the 2000s) were denied entry into the upper stratum of fine art, namely the self-supporting fine artists. Thus, A. was fated to be part of the nascent counter-elite. We must admit that A.’s behaviour, characteristics and aesthetic affiliations certainly contribute to his failure to gain a stable foothold in the art world that had been (if not promised then) offered him by the system.

Yes, all very pat. In this explanation, we overlook A.’s wilful deviance. If he wanted advancement, all A. had to do was conform by producing art that could be commissioned by the state. We cannot attribute A.’s failure entirely to his situation as a member of the surplus elite but rather to a conscious drive to resist acceptance on the terms set out by the art establishment. It is the criminal’s urge to defy authority – or to seek personal gratification disregarding the prevalent norms – that we see in A. and Malry. When Johnson has Malry say “I am a cell of one”, he gets his protagonist to state his position as both a dedicated agent of disruption but also an atomised individual, without power to effect lasting change because he acts alone. Both characters are victims of their naivety, expecting the world to be governed by fairness not by power, and who slowly come to realise their folly.

In his own way, Malry is an failed artist and A. is a failed criminal. Such is the fate of many of us.

The Naked Spur is published by Exeter House on 23 May

Reading from this here post duly 'inserted' into L'étranger radio show of 25-05-25. Track 27 - > https://www.radiopanik.org/emissions/l-etranger/show-505-wanton-adel-reeving/