Further thoughts on Vermeer

Further to my review of the current Vermeer exhibition (in The Jackdaw), I give some thoughts on issues the catalogue raises.

[Image: Vermeer, The Milkmaid, c. 1658-9, 45.5 x 41 cm, oil on canvas, Rijksmuseum]

A full review of the current Vermeer exhibition (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 10 February-4 June 2023; reviewed from the catalogue) will appear in The Jackdaw, May 2023 issue. (To buy that issue, subscribe here.) This present article presents further reflections on Vermeer, in the light of the exhibition.

The large catalogue (320pp) includes an illustrated list of Vermeer’s 36 or 37 paintings. There are no known drawings. There are no particular surprises. The terrible Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (c. 1670-2; Leiden Collection, New York) is still treated as authentic, when at least some of it is not. I adjudge the head, hands and wall to be posthumously completed; remarkably, technical analysis shows that the canvas comes from a bolt that Vermeer had already used for an authenticated painting and that the wretched yellow shawl is consistent with techniques and materials common to Vermeer’s established oeuvre. Girl with a Flute (c. 1664-7) is still considered on the fringes of Vermeer’s art. It is very poor but the materials and technique are of Vermeer. There is the idea that this is a work made under his supervision. Yet the conventional wisdom is that Vermeer had no studio or assistants (other than his older children doing paint grinding), so whom does this “circle of Vermeer” consist? No suggestions are put forward.

Overall, the catalogue is recommended. It ties together new research and illustrations of restored paintings, summarising what scholars currently understand of this most revered but also mysterious artists.

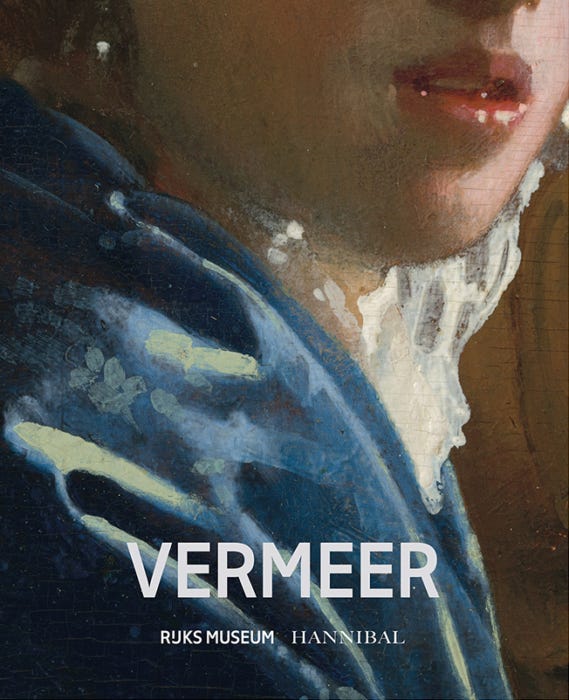

If one could make a criticism of the catalogue, it would be the observation that nowadays editors are often enamoured of the micro-photography made possible with digital cameras and the we consequently catalogues are chockful of close-up photographs of details. We tend to gain an insight into how material was used at the expense of seeing what it was used for. Editors tend to be led by what material is available rather than how that material might be used most judiciously. Novelty drives editorial decisions and the attention of technical specialists, knowing as they do that never-before-published images have appeal when there is no new paintings or information to publish. In many reproduction the matter disappears and we get the image without a sense of the materials; yet today we often get the stubborn base material dominating our impressions without an abiding memory of what ends that material is manipulated. For example, the first pages of Vermeer are extreme close-ups, which emphasise the painterly qualities of Vermeer’s art, making him the spiritual antecedent of Turner, Monet and de Kooning.

Once anything is reproduced above life size, it tends to stray from what it primarily is (a depicted form) towards what is only secondarily (manipulated matter). This is allied to a tendency towards demystification of art and the treatment of art as a narrative of development, including discussion of preparation, sources, alternate versions and pentimenti. In other words, it is the art critical faculty let loose upon a great work of art in order to explain it dissected rather than present it whole. As a critic, I am aware of this danger in my own activities.

Ironically, it is being a painter of light rather than of matter that distinguishes Vermeer from his close contemporaries Pieter de Hooch, ter Borch, Maes, Jacobus Vrel and others. It is the revolutionary treatment of the artefacts of light (reflection, highlight, speckle, un/focus) rather than theme, repertoire or materials that are special, as is demonstrated in the illustrations of paintings of others. A surprising number of them avoid the anecdote, humour, moralising, incident and puzzles that we associate with Dutch Golden Age genre painting, which initially makes us think that Vermeer is actually more typical of his time than we commonly assume. However, once one understands that Vermeer’s subject is light, shadow and textures, with the ostensible subject matter being secondary, we see how Vermeer could come to home his technique and dwell on technical matters far more than his fellow painters. We can think of painters of this time falling into categories who take as their prime concern iconography, objecthood (including animals and people), morality/narrative or (most rarely) the pictorial/optical. So, it is ironic that the plethora of details in the catalogue divert Vermeer’s paintings to the realm of proto-abstraction, which stresses the materiality of his painting approach.

Pieter Roelofs, Gregor J.M. Weber (eds.), Vermeer, Rijksmuseum, Thames & Hudson, 2023, hb, 320pp, fully illus., £50, with versions in English, Dutch, German and French, Rijksmuseum/Hannibal, hardback, €59

Appendix:

List of Vermeer paintings included in the exhibition, according to the Rijksmuseum.

1. A Lady Writing, 1664–67, National Gallery of Art, Washington

2. A Young Woman seated at a Virginal, c. 1670–72, The National Gallery, London

3. A Young Woman standing at a Virginal, 1670–72, The National Gallery, London

4. Allegory of the Catholic Faith, 1670–74, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

5. Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, 1654–55, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

6. Diana and her Nymphs, 1655–56, Mauritshuis, The Hague

7. Girl Interrupted at Her Music, c. 1659–61, The Frick Collection, New York

8. Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, 1657-58, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

9. Girl with a Flute, 1664–67, National Gallery of Art, Washington

10. Girl with a Pearl Earring, 1664–67, Mauritshuis, The Hague

11. Girl with the Red Hat, 1664–67, National Gallery of Art, Washington

12. Mistress and Maid, c. 1665–67, The Frick Collection, New York

13. Officer and Laughing Girl, 1657-58, The Frick Collection, New York

14. Saint Praxedis, 1655, The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo

15. The Geographer, 1669, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

16. The Glass of Wine, c. 1659-61, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

17. The Lacemaker, 1666–68, Musée du Louvre, Paris

18. The Love Letter, 1669-70, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

19. The Milkmaid, 1658-59, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

20. The Procuress, 1656, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

21. View of Delft, 1660-61, Mauritshuis, The Hague

22. View of Houses in Delft, known as ‘The Little Street’, 1658-59, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

23. Woman Holding a Balance, ca. 1662–64, National Gallery of Art, Washington

24. Woman Reading a Letter, 1662-64, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

25. Woman with a Pearl Necklace, c. 1662-64, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie

26. Woman Writing a Letter, with her Maid, 1670–72, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

27. Young Woman Seated at a Virginal, c. 1670‐72, The Leiden Collection, New York

28. Young Woman with a Lute, 1662–64, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Thanks for a very interesting article. I myself believe form is more important than content. Maybe, 51 to 49 but still . . .

Have you seen this? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGQmdoK_ZfY