"Frank Auerbach: The Sitters"

As the exhibition in London of Frank Auerbach's portraits comes to an end, I look at the catalogue.

[NICOLA BENSLEY, FRANK AUERBACH: A MORNING IN THE STUDIO, 2015, Eight silver gelatin prints, 50.8 × 40.6 cm / 20 × 16 in (sheet), edition of 25. Copyright Nicola Bensley.]

A substantial exhibition of paintings by School of London painter Frank Auerbach (b. 1931) is now reaching its last days. (23 September-16 December 2022, Piano Nobile, 96/129 Portland Road, London, W11 4LW, www.piano-nobile.com.) This review is from the catalogue only.

Auerbach was born in Berlin and arrived in England in 1939. He studied painting at Borough Polytechnic by David Bomberg (1947-53, alongside Leon Kossoff), St Martin’s Art School (1948-52) and the Royal College of Art (1952-5). He became friends with Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and R.B. Kitaj who became the nucleus of the School of London, which upheld the engagement with traditional painting techniques, figuration and the primacy of the human body (especially in the form of portraiture) as the prime subject of art.

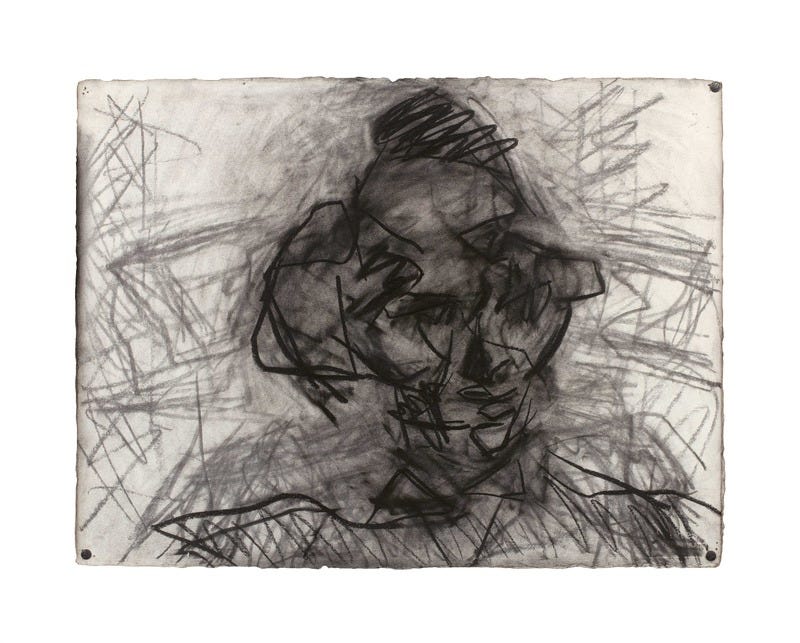

[Frank Auerbach, HEAD OF CATHERINE LAMPERT II, 1978-79, Charcoal and black chalk on paper, 57.4 × 77 cm / 221⁄8 × 30 ¼ in. Copyright Frank Auerbach.]

Like other painters in the London School, Auerbach left many of his sitters unnamed. As with other artists, in their last years and posthumously, identities and biographical details emerge about the sitters. This comes with the process of historical, biographical and archive research that accompanies the elevation of the art to the status of classic. Also, as sitters die, pictures they owned enter the secondary market. Researchers make a point of asking for memoirs by and interviews with sitters. Biographers also seek out primary information from sitters.

Auerbach’s approach is to create a picture over multiple sessions from life, sometimes reworking the entire painting or drawing each time. He would often scrap a panel clean of paint and work from scratch in a following session. Over 40 or so sessions, a sheet of paper might be erased of its charcoal or graphite marks so often that is becomes rubbed right through, then patched be before the drawing is finished. The sprezzatura finish to the paintings belies the concentration put into each over a prolonged period, although the visible surface paint maybe indeed have been applied in one session. The impasto is so thick that it takes months to dry to state in which it can be hung vertically without slipping. An oil painting sometimes takes many years to dry, sometimes taking on a shrivelled appearance. A more schematic approach using encaustic wax would eliminate paint shrinkage, but Auerbach is not that type of painter.

The notes here relate to known portraits subjects of Auerbach, whether or not their pictures are among the exhibits at Piano Nobile. Some – such as Kossoff and Freud – are famous; others – such as curator and author Catherine Lampert – are known associates of the artist. Other initials reappear in exhibition listings over years without viewers knowing the identities. Julia is Auerbach’s wife and E.O.W. is Stella West, one of Auerbach’s lovers. Is usual, the reason artist’s conceal the identities of sitters and models is because exposure brings to light the tangled skein of personal affairs, failings in fidelity and awkward chronology. Is it any wonder that artists prefer to keep such information concealed for as long as possible. Auerbach’s determination is also shown in his loyalty to sitters; he has worked with some for decades.

[Frank Auerbach, Head of E.O.W., 1972, Oil on board, 27.9 × 35.6 cm / 11 × 14 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach]

Another sitter was Sandra Fisher, artist, muse and wife of Kitaj. Kitaj produced a memorable pastel of Sandra and Auerbach seated at a table (illustrated here). Sandra also sat to Auerbach, here in one drawing and one painting. Naturally, Auerbach’s sitters have been taken from individuals in the art world. Stephen Finer and Laurie Owen are painter colleagues; James Kirkman was an art dealer; David Landau is an art collector. Michael Podro the painter met before he began his career as an art historian, when they were both art students. Podro and his wife Charlotte collected Auerbach and were painted and drawn by him; Podro wrote about Auerbach – the essay is reprinted here. There is are discussions of the Podro-Auerbach friendship by Natasha Podro, Michael’s daughter, and by Luke Farey. The introductory material is a short foreword, a brief essay by art critic and portrait subject William Feaver and an interview with the artist by Martin Gayford; the latter are both old pieces (dating from 2009 and 2001 respectively), although the interview includes unpublished parts. There are commentaries that accompany the 41 paintings and drawings by Auerbach. There are new comments and information about sitters and their experiences of posing for Auerbach.

There also are eight photographs of Auerbach in his studio, shot by Nicola Bensley in one morning in 2015. The studio is famously small and spartan, situated in the Mornington Crescent (near Euston) and was previously occupied by (consecutively) Kossoff, Gustav Metzger and Frances Hodgkins. Auerbach’s studio is not as famous as Bacon or Freud’s but is an important part of the creation process. He has worked in the studio almost every day since moving there in 1954. As with Freud, sitters mention the powerful impression the studio makes upon them. The small, paint-encrusted cell is the site of most of his painting. Like Freud, Auerbach wrestles with paintings, displaying signs of frustration and tension as the image (usually) fails to cohere.

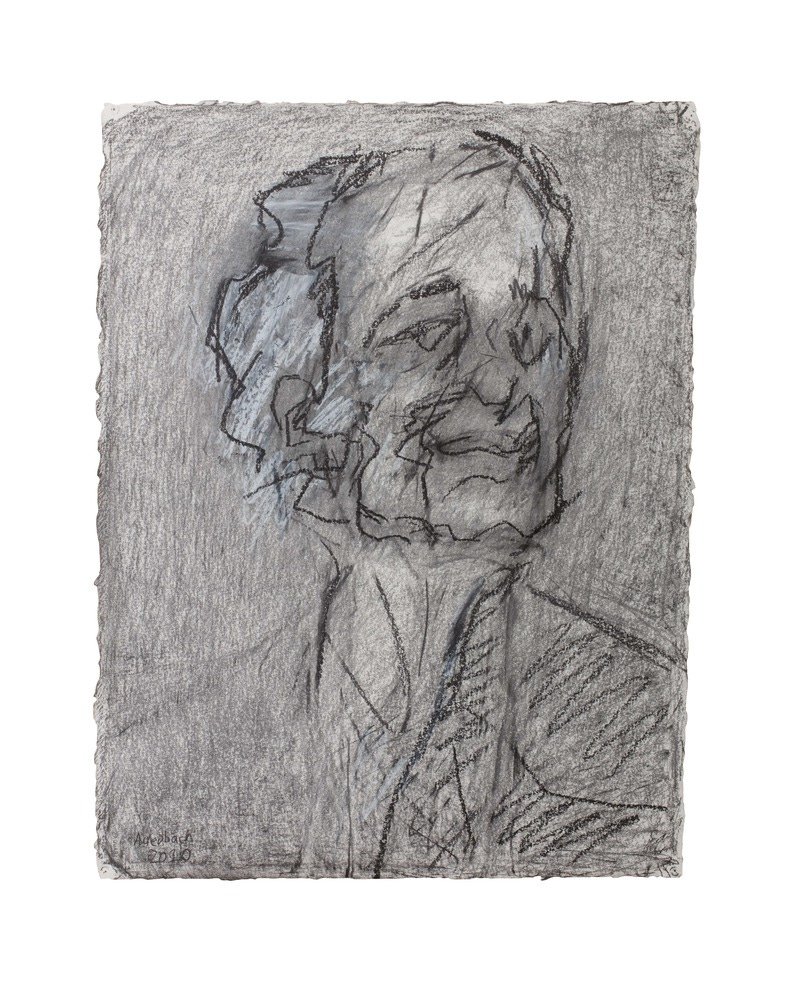

[Frank Auerbach, S E L F – P O R T R A I T, 2 0 2 0, Graphite, white chalk and Indian ink on paper, 75.8 × 58.4 cm / 297⁄8 × 23 in. Copyright Frank Auerbach]

What of the new art? There is a self-portrait drawing from 2020 – very light in touch and tonality – and we are promised further unpublished works in an updating of Feaver’s catalogue raisonné of Auerbach’s paintings, published this year. There is also a new head, which is daring; the black calligraphy seems quite detached to the slurred yellow brushwork below. The self-portrait drawings have a degree of liberation and dignity, as if the artist had freed himself of his previous penchant for Rembrandtian gloom and dramatic chiaroscuro.

The book gives a good overview of the artist’s achievements, presenting new information and publishing unseen art. It provides thorough provenances and exhibition/literature history for each piece; a chronology is also included. The production quality is very high. Getting the full intensity of the colour range is often tricky with Auerbach and this catalogue gets commendably close to the originals. Although the price of this book is high, it will become a coveted treasure for Auerbach connoisseurs.

William Feaver, Martin Gayford, Luke Farey, et al., Frank Auerbach: The Sitters, Piano Nobile Publications, 2022, cloth hardback with paper-band wrapper, 176pp, fully illus., £100, ISBN 978 1901192629