David Jones, Distributism & the Benedictine Option

A current exhibition set me thinking about the fate of a notable artist commune.

There are many instances of vanguard artists stepping out of civilisation into the primitive. Be it Gauguin and Laval in Martinique, Picasso in Gósol, Matisse in Tahiti, Pechstein in Palau or a dozen others artists, we can recall modern European men going to the well of barbarous backwardness in order to drink of its invigorating water, only to discover it tainted by colonial microbes – the religion, clothing, education, laws, consumer goods and other appurtenances of the West. An associated practice is going to a less developed part of one’s own country to immerse oneself in the simple life. Gauguin and Denis treated Pont Aven as their artless backwater, where the girls still danced in traditional bonnets and no one read the Paris papers.

In 1907, English artist and typographer Eric Gill (1882-1940) set up a commune in a the Sussex village of Ditchling. Gill was a mildly vanguard artist who would become a Catholic convert. His faith became a constant source of inspiration for his art. Gill’s views were a mixture of Modernism, conservativism, and Distributism (Catholic communitarianism). Distributism holds that both laissez-faire capitalism and Socialist control economies damage natural social structures of community and family and have a tendency to degrade the goods produced, replacing the artisan with the employee worker. Gill’s Distributism has been misinterpreted as Socialism, mainly because the latter is better known and understood than Distributism.

The Ditchling community was associated with a Dominican order of friars, who led worship; attendance at services was expected by Gill to be at least daily for all members of the community. Work, worship and living were mingled in a way that deepened the social implications of the earlier Arts & Crafts Movement, of which Gill had been part but of which he had become more critical. Gill’s aim was to form a guild, as advocated by Ruskin and Morris, but have this tied to religious purpose. It was conceived to be distinct and separate, with the goal of countering secular materialism found in mainstream society, manufacturing and art. In 1924, Gill resigned from the business partnership, due to disagreements over the future of the collective. He relocated, taking his break-away group to a remote disused monastery in mid-Wales, at a village called Capel-y-ffin.

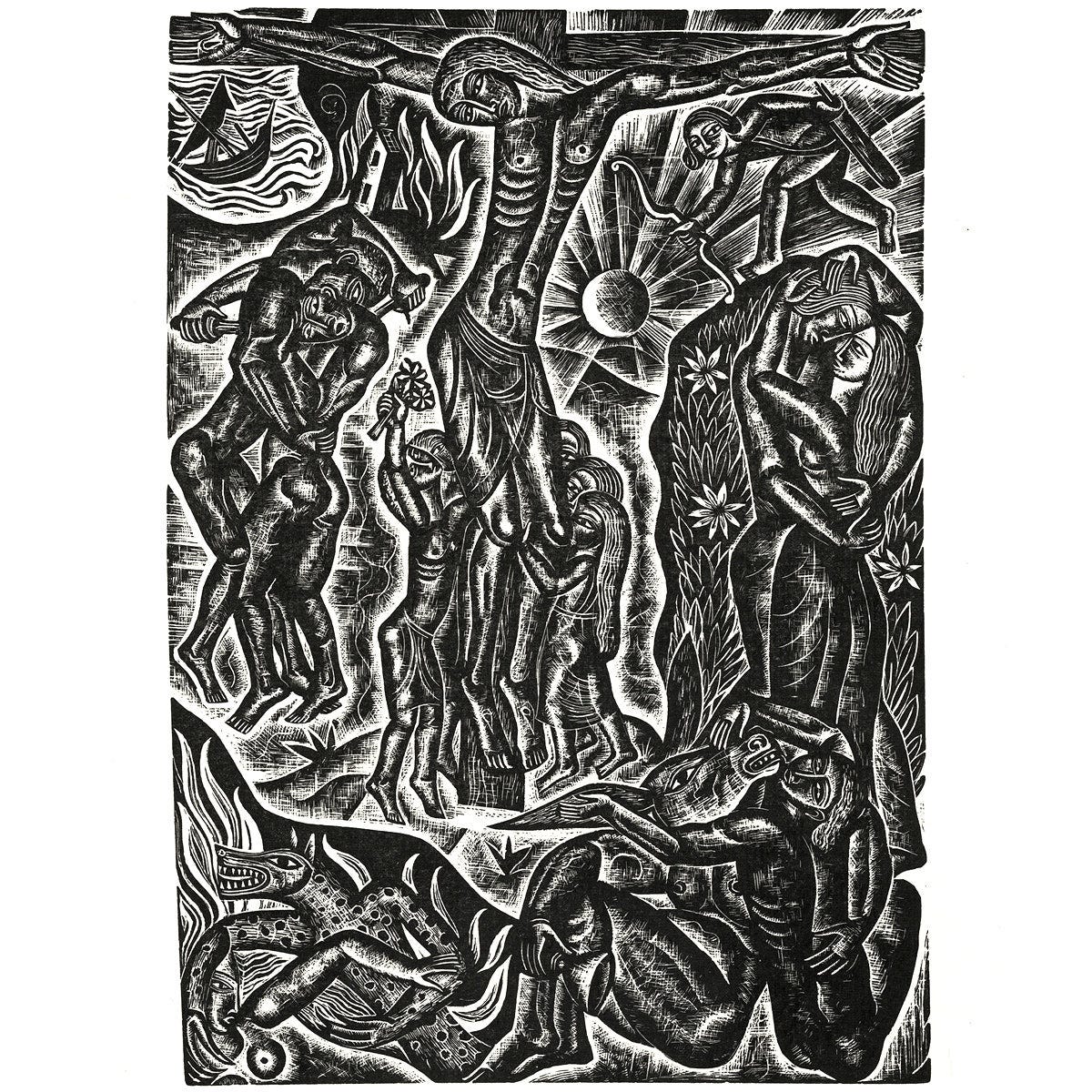

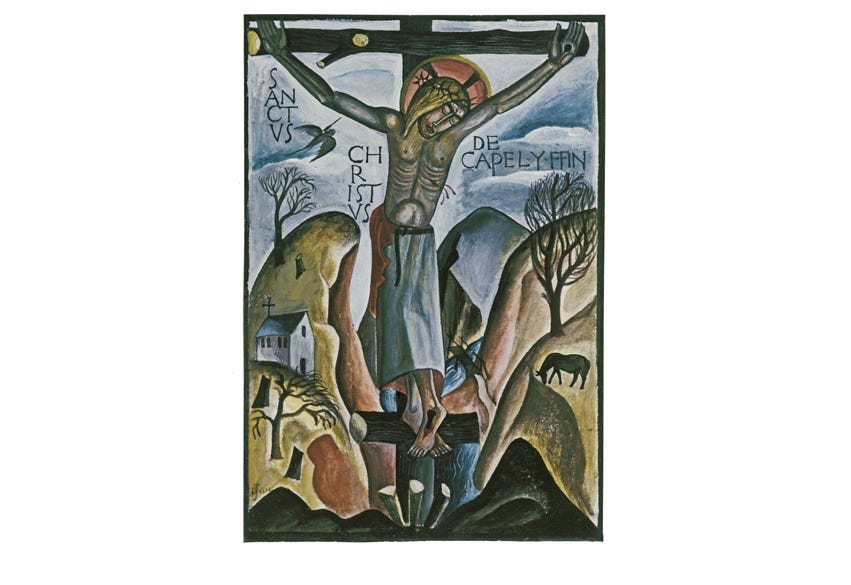

Last week I went to see the exhibition “Hill-Rhythms: David Jones and Capel-y-ffin” (1 July-29 October 2023, Y Gaer, Brecknock Museum, Art Gallery and Library, Brecon) in Wales. The display collected a body of wonderful landscape paintings, portraits and wood-engravings made by British artist David Jones (1895-1974) over the years 1924 to 1927, when he made extended stays with the Gill family at Capel-y-ffin, continuing a practice begun while the group was in Ditchling. Jones had fought in some of the major battles of the Western Front during the Great War, which had left him with permanent trauma. Jones’s conversion to Catholicism in 1921, somewhat due to Gill’s example, should be seen (in part) as a response his wartime experiences. In outlook, Jones was influenced by Gill and largely aligned with his social and artistic aims. Jones was religious, an artistic Modernist, socially conservative and disillusioned with modern life. While in Capel-y-ffin, he produced Biblical scenes that incorporated the local landscape and utilised an idiom based on pre-modern religious art.

Jones was fascinated by the early Christian history of Wales, land of his fathers. He read widely on the Welsh mythology, King Arthur and learned to speak Welsh. For Jones, inhabiting Capel-y-ffin was a profound homecoming, not despite his childhood on the outskirts of London but because of that previous separation from his ancestral roots. Jones, still timid and plagued by complexes following the war, welcomed the chance to immerse himself in a landscape that had family and cultural links which gave his life greater richness. He painted hillside views, farm labourers and farmyard animals. He looked at the ponies in the fields and considered them descendants of the steeds of Arthur and his knights – analogous to him and his Celtic brethren, humble sons of great forebears. This sentiment animates his great poem In Parenthesis (1937), which draws explicit parallels between the Welsh soldiers of Tudor and ancient Celtic times and those who fought in World War I.

The exhibition got me thinking about the Benedictine Option. (I use “Benedictine Option” in preference to Rod Dreher’s “Benedict Option”, which is his specific platform, because I wish to speak about the general concept.) The Benedictine Option is conceived on the basis that an order of novitiates can found and maintain centres of learning in defiance of the values of mainstream society. The thinking is that the forces of modernity are so overwhelming that open outright opposition by conservatives and reactionaries is not viable. Instead, men of quality should retreat from the modern world in order to conserve forms from contamination, transmit traditions that are discontinued elsewhere, preserve cultural material that would otherwise be destroyed and sustain eternal virtues that are subverted by progressive materialist society. This would involve the establishment of networks of makers, thinkers and scholars, and the founding of centres of learning which are not public in nature but private and accessible only to initiates. This sounds very close to Gill’s guilds in Ditchling and Capel-y-ffin.

The difficulty of sustaining a community that requires supplementary income – however otherwise self-sufficient it is in other respects – puts that community into contact with the outside world. To be fair to Gill, he never envisaged his guilds being cut off from society as a whole. He himself took on major sculptural and book-illustration commissions in order to support his family. The tensions inherent in a closed group that needs materials, clothing, books, medicine and other goods which it cannot produce, are ones which must be addressed and overcome in a pragmatic fashion. The larger the group, the more possible it is to sustain provision of goods and services within the group, yet the greater the lack of control and conformity within the group. Only the most tightknit ethnic and religious communities can maintain such cohesion, and then only if they remain an organised minority with clear boundaries that separate them from outsiders. Considered from a value-free perspective, the social unit closest to Gill’s commune of volunteers (and their dependent family members, perhaps somewhat less committed) are the sect or the cult. That is a subject for another article, perhaps.

There are other pitfalls, aside from the practical ones. Does the dissenter who turns his back on mainstream society risk becoming ossified through attachment to a distant past which is irrecoverable and is actually a fantasy retreat constructed according to contemporary mores? I am thinking here more of the radical conservative rather than the reactionary, for the reactionary understands that the past is gone and that the future cannot be recovery or restoration of a historical system but something freshly fashioned from eternal virtues. In that sense, I see Gill as a radical conservative and Jones as romantic and reactionary. The art that Jones made in Wales was not conservative, although it does evoke Medieval carvings and devotional woodcuts. His watercolour views of the fields, trees and mountains around Capel-y-ffin are drenched with the sophisticated naivety of Chagall and display familiarity of Fauvist technique.

The idea of having a retreat where artists and creators can make material that incorporates the values of a conservative community has persistent appeal. Artist and writer retreats are common, but they are almost all for short durations. Distributism, as a socio-economic system, depends on stability, which requires a core of committed participants. Gill’s guilds proved to be relatively short lived, in that they did not outlast their founder – surely a key criterion of sustainability. (Again, one of the keys to the maintenance of the cult is the charismatic leader and authoritarian control.) As Alisdair MacIntyre, the writer who coined the term “the Benedict Option” noted, any relatively closed community attached to a fixed place and set core values needs to be able to either breed or induct a younger generation to maintain continuity. Artists considering founding a Benedictine-style community would do well to read about Gill’s experiments.

Today in Britain, Gill is mainly known in the popular media for his abnormal sexual proclivities, which have drawn the ire of campaigners and commentators. His ideas regarding the social functions of art and the community roles of artists are not raised much, even by proponents of Distributism. The examples of Jones and Gill are worthy of greater scrutiny by not just artists but anyone supportive of the Benedictine Option.