Carlo Mollino, Italian Architect

Mollino's achievements in architecture were only part of this complex and daring man's life.

Italian architect Carlo Mollino (1905-1973) was the epitome of the glamour and suavity of Italian Modernism. Living and working over the golden period of the 1930s to 1970s, Mollino’s architecture (grand and modest) and his photographs embody Italomodernism. His career spanned the economic resurgence of Italy in the post-war period, as well as the foundations of during the Fascist period.

Mollino was a playboy, with the movie-star charisma, whether he was inspecting one of his buildings, horse riding or driving a sportscar of his own design. He stands out to us, lodged in the age of specialisation, as a qualified architect who designed race cars, flew aerobatics and was a qualifier skiing instructor? The swashbuckling Mollino seems barely believable in the range of his talents and ambition.

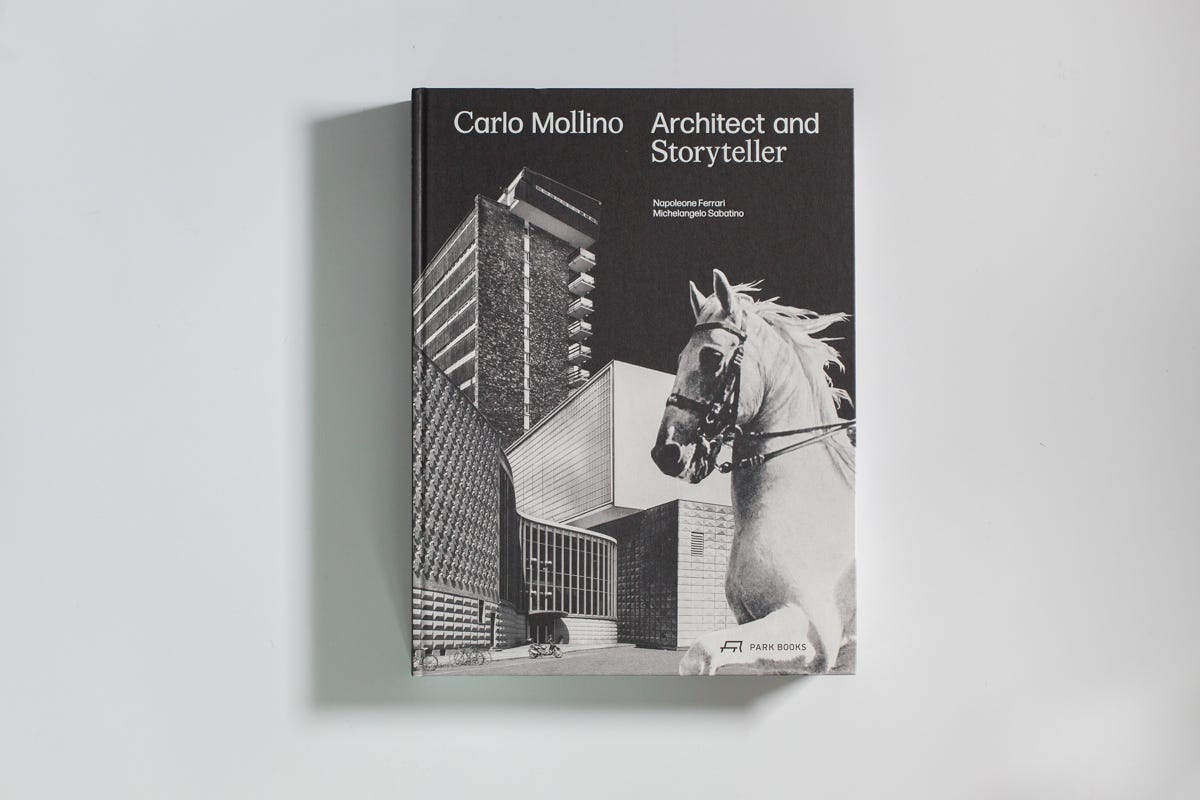

His foundations were solid. His parents were Jolanda Testa and Eugenio Mollino, who was a prolific architect-engineer, with 300 erected structures to his name. After studying in Turin and Belgium from 1925 to 1931, including a period of compulsory military service, the younger Mollino graduated as an architect. He had grown up in Italy of the 1910s and had been influenced by the Futurists’ exhortations to take up the efficiency, action and élan of sports as an aesthetic. A recent book on his architecture (Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller, Park Books, 2021) identifies Mollino’s milieu. “During Mollino’s formative years from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s, Turin was an epicenter in art, cinema, and literature. [Turin had] a dynamic architectural scene during this time.”[i]

Mollino was determined to improve upon his father’s stolid achievements. In contrast to his father’s conventional buildings, including Turin’s largest hospital, Mollino wanted to dazzle people and flatter his clients’ sense of daring. (However, relations between father and son were good; Carlo Mollino used his father’s studio office as his own until his death.) Rather than following the Fascist trend in architecture – consisting of monumental style and imposing presence – Mollino was inclined to follow Bauhaus styles, lightness, natural forms and the spirit of Surrealism. The latter makes its felt strongest in his photo-montages of interiors, including sculptural fragments and unexpected figures. In one photograph, a woman in evening dress and a fur stands inside a built-in wardrobe; beside her is a cast of a statue fragment.

Mollino’s career displays the ambivalence of Italian architects towards Fascism. His style could be seen as antithetical to it, with cantilevered structures undermined the solidity that Fascism wished to convey. However, he was patronised directly and indirectly by the Fascist government, as all were who built civic structures. The offices for the Farmers’ Federation (Cuneo, 1933) have the boldness of Modernism and Art Deco, with horizontal bands of windows and a rounded wall. The outside was emblazoned with a line of Mussolini’s propaganda – not a matter the architect had any influence upon. In Voghera, he designed the local Fascist headquarters.

His early masterpiece must be the Horse Riding Club (Turin, 1937-40), which has sweeping horizontal lines and textured surfaces that play with light and pattern. Glass bricks, grills, glass balustrades, lattices and large windows made the building extremely light and airy, dematerialising structural elements, introducing surprising shadow patterns. It was acclaimed by architectural commentators and in art journals. Sadly, it was demolished in 1960.

Ski lodges used cantilevered bases to cope with sloping foundations and steep roofs to prevent accumulation of snow. Interiors use wooden planks on the floors and walls and natural-finish wooden furniture which are an extension of traditional rusticity. The large hotel (Cervino, 1945-52) is effective but not integrated in the landscape nor sympathetic regarding the vernacular architecture of an Alpine village. A chalet for hang-glider flyers features exposed beams supporting a wide pitched roof, echoing the shape of a hang-glider.

The slowdown of architectural construction during the war was used by Mollino to do research that would subsequently be published in books on architecture (1947), photography (1949) and downhill skiing (1950). His Il Messaggio dalla Camera Oscura (Message from the Darkroom) was first ever comprehensive manual of photography published in Italian. After the war, Mollino taught at Turin Polytechnic, something that seems to sit oddly with his love of adventure, yet he was successful, diligent and respected as an educator.

The dramatic Opera House (Turin, 1950-2) features dramatic curves in the auditorium, mainly for acoustic reasons. Vertical detailing in the sweeping balcony edges and the pilasters echo the pipe organ at the back of the stage, also acoustical in nature, but induce a sense of immersion and cohesion in visitors. Damaged by Allied bombing, Mollino was selected to restyle the existing building and add entirely new decoration and fittings.

From monument to auditorium, from cable-car station to exhibition hall, Mollino’s designs are diverse, although many did not reach construction stage. Writers tagged Mollino as prey to eclecticism, a charge he freely admitted. As authors Napoleone Ferrari and Michelangelo Sabatino note, “In his work he purposely mixed cues from twentieth-century movements such as Futurism, Surrealism, Expressionism, Rationalism, and Organicism in search of a personal synthesis. He also drew on and transformed elements from antiquity to the early modern period of the Renaissance and Baroque. He juxtaposed modern and traditional materials, artisanal and industrial building techniques. Mollino could appropriate various styles or techniques as if they were part of a vast, temporally diverse vocabulary made available to the twentieth-century architect.”[ii]

His modernism was never detached from craft, as he took care to supervise workers, observing their skills and the nature of the materials. Like many architects, Mollino became involved in designing furniture to enhance and expand the built environments he made. The drawings of airships made by the boy Mollino indicate a longstanding fascination with flight, something that he would cultivate by taking flying lessons, qualifying in 1956. He designed a series of planes for aerobatics, which were never constructed.

In 1955 Mollino designed the Bisiluro Damolnar sportscar (based on the Osca 1100) for the Le Mans 24-hour Race that year. Already well acquainted with the flowing lines and smooth surfaces of Modernist designs, Mollino adapted the chassis and designed the shell to make it as efficient as possible. Its dramatic twin-torpedo shape, with the driver sitting in the right side, is on display in Leonardo da Vinci Museum, Milan.

In later years, Mollino spent increasing amounts of time on photography. Back in the ‘30s and ‘40s, he had curated his appearance my directing photographs of him, by fellow artists and by himself. In the photographs of his last two decades, his subjects were mainly young women, in shots that could be described as “glamour” or “cheesecake”. His Polaroids and prints, some carefully adjusted by the photographer, have received attention in articles and a recent book.

Architect and Storyteller is a an excellent survey of Mollino’s architectural designs and constructions, with a good commentary on Mollino’s complex legacy. Beautiful photographs and inclusion of new translations of Mollino’s texts make this an indispensable guide to the man and his works.

Napoleone Ferrari, Michelangelo Sabatino, Carlo Mollino: Architect and Storyteller, Park Books, Zurich, 2021, hardback, 456pp, 502 col./45 mono illus., CHF 99, ISBN 978 3 03860 133 3

[i] P. 25

[ii] P. 53