Byzantinism, Darwinism and Leontiev’s “amoral aesthetics”

Russian thinker Konstantin Leontiev's conceptions of cyclical civilisations relate to aesthetics as well as political autonomy.

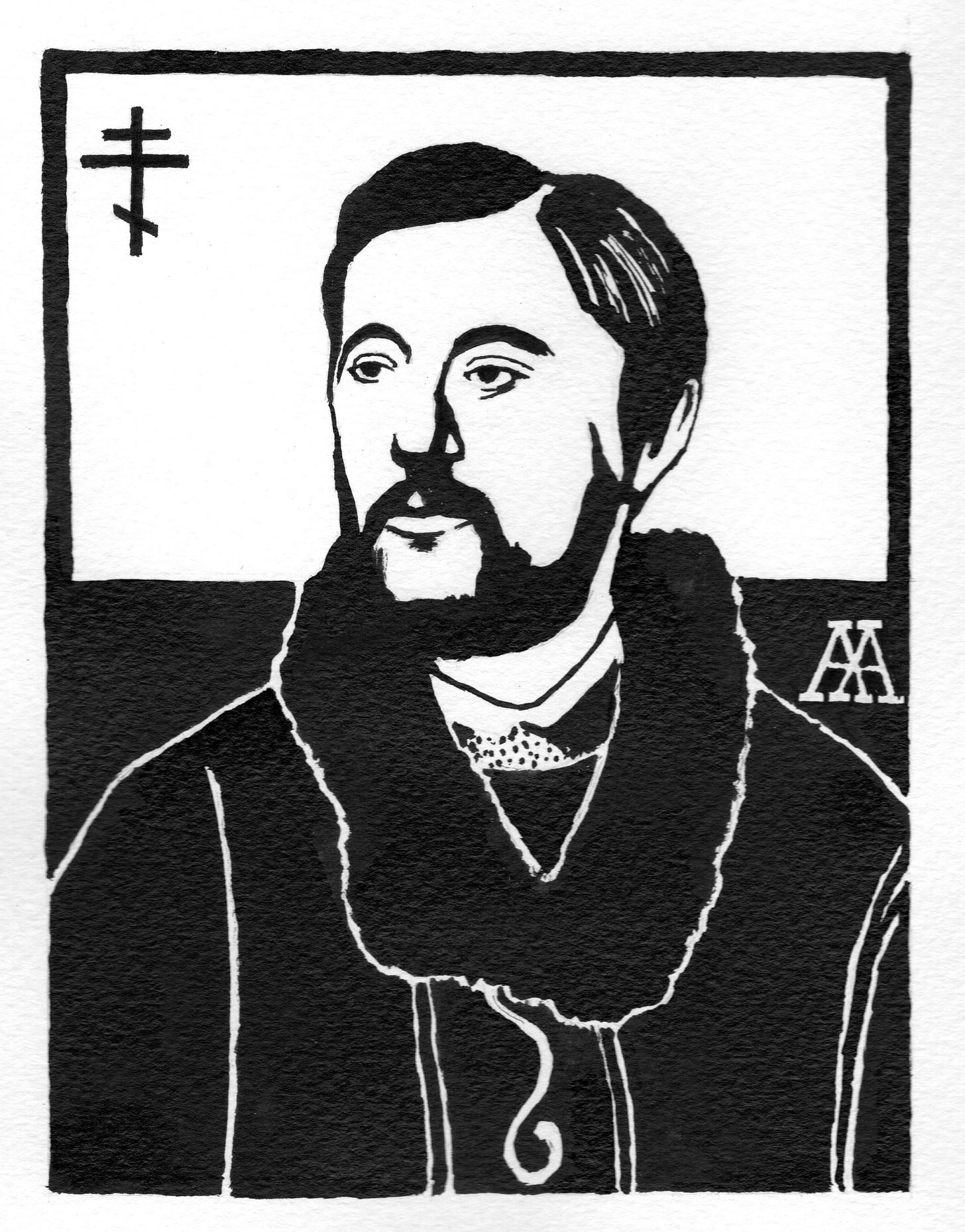

[Alexander Adams, “Konstantin Leontiev”, ink on paper, 2023]

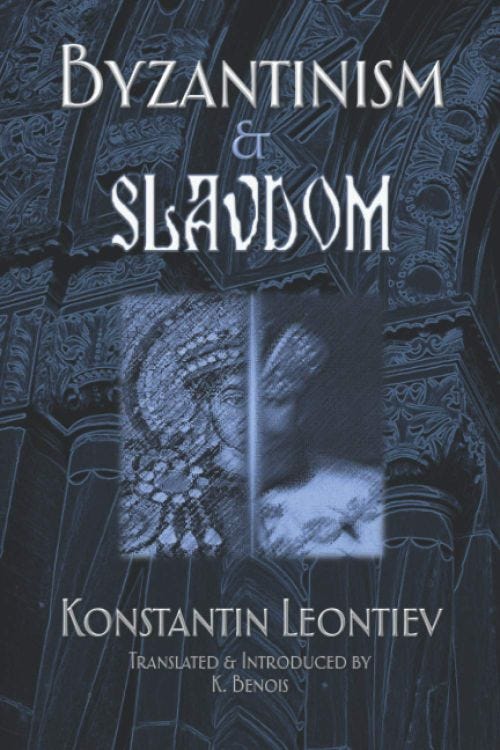

Russian Pan-Slavist author Konstantin Leontiev (1831-1891) set out the character of Slavs and nature of Slavism – within a socio-political movement he called “Byzantinism” – in the book Byzantinism & Slavdom (1875). As a dedicated Pan-Slavist and Russian patriot, he saw his people’s destiny linked to its physical culture, which was dependent upon political circumstances and historical constraints. He wrote that kinship was not enough; shared physical culture was necessary to make a coherent civilisation. He opposed modern nationalism because it presaged the managerial state, with its attendant liberalism and materialism

This article will outline Leontiev’s conception of “amoral aestheticism” and it incorporation of Darwinism into a philosophy not widely known in the West. We shall also see how Leontiev’s aesthetics compare to those of Nietzsche, to whom he is frequently compared.

Slavism and Byzantinism

After serving as a medic in the Crimean War, later as a provincial doctor, then attempting to make a living from writing (drama, fiction and journalism), Leontiev found more regular employment in the diplomatic corps. This period of travel allowed Leontiev to form impressions of Slavs and other peoples, seen firsthand. His increasing nationalistic feeling and religious commitment found expression in his writing. His outlook is a mixture of vaunting patriotism and disgust at the liberalisation of Russia under the control of a small but influential class of bourgeois intellectuals and reformers, intent on matching the changes in the West.

Leontiev saw the splintered character and the disparate fortunes of the Slavic peoples as having impaired their cultural development. He commences Byzantinism & Slavdom by stating that Slavic culture has not followed the trajectory of Western Europe. Russia did not develop at the same rate as Central and Southern Europe. “Our Renaissance, our 15th century, the beginning of our more complex and organic flowering, our unity in multiplicity, so to speak, must be sought in the 17th century, during the reign of Peter the Great, or at least the very earliest in fleeting glimpses found during the life of his father.”[i]

Leontiev did not overlook the contradictory strands of Slavdom, with its multiplicity of languages, religions, practices and levels of autonomy. He therefore did not think that fusion of the peoples was possible, considering the divergence of groups. He did think there was a core that remained among them all, one which came from the Byzantine Empire. He understood Slavism as having political, social and aesthetic dimensions (expressive of the Slavic character), which would be inherent parts of the Byzantinism political project. The distinctiveness of Slavic art, when not diluted or polluted by outside influence, was proof of the people’s genius. “Byzantinism also provides very clear ideas in the realm of art or aesthetics conceived more generally: fashion, customs, tastes, clothing, architecture, utensils; and given all this it is easy to imagine oneself a little more or a little less Byzantine.”[ii]

The enemies of Byzantinism were not only external but internal: the liberal reformers who sought to dismantle Slavic feudalism, autocracy, piety and attachment to the land. When at their purest – ethnically and culturally – Slavs were capable of matching the West. It was due to the historical disunity and vassalage of the peoples that the Slavic Renaissance had been curtailed. Life under the rule of bureaucratic regimes had curbed the Slavs who, like all peoples, flourished under despots and hierarchical systems suited to their nature. Although an Ottoman governor in the Balkans was hostile to his conquered charges, the Bulgarian and Serb were at least protected from the liberal influence of Western Europe (and even the USA), which the Slavic liberal in Prague or Budapest welcomed. Paradoxically, it was under the yoke of the Turk where a Slav clung most tightly to his culture.

His theory of history is partly cyclical – that all living animals and systems experience a common set of stages – and partly linear, for he believes in the Christian dogma and the inevitable resolution of man’s destiny in the apocalypse and Judgement Day. Some have compared Leontiev’s theories to those of Spengler’s relating to the decline and decay of civilisations on a grand scale.

Amoral aestheticism

Aesthetics were a demonstration of man’s essential nature because they transcended use and were related to the higher appreciation of the intellect and cultivated sensibility, divorced from utilitarian applications for art. However, unlike many Christians, Leontiev did not understand aesthetic appreciation as divinely inspired nor did he see the role of art to provide moral instruction, which would be an instrumentalist view of art. Here is an explanation of Leontiev’s aesthetic position, which has been called “amoral aestheticism”.

“His conception of the world positioned man not as the focal point of creation, but as an instrument through which beauty could be achieved. […] Autocratic and hierarchical state forms were preferable not because of their ability to maintain order, but because of their ability to draw beauty out of great contrasts, both within and without, to orchestrate them. […] He recounts explicitly that he found great beauty in the archaic, small communities under the rule of the Turkish sultan, the same beauty he saw fading from his homeland as it modernised and emulated Europe, and this beauty he attributed to authoritarian rule, exclusionary ethnic and religious laws, and rigid class distinctions.”[iii]

Thus art was not in service of either personal expression nor (necessarily) in the witnessing of God’s creation and moral instruction; it was amoral – devoted centrally to providing transcendental pleasure or the sublime experience. In this respect, Leontiev arrives at some of the same conclusions as the Aesthetic Movement’s Walter Pater and Théophile Gautier, although surely without knowledge of the latter’s “art for art’s sake” credo. Nietzsche himself was scornful of the idea of aestheticism, finding that art devote of moral or intellectual content an abrogation of the artist’s task to fuse the rational and irrational and act as a speaker of divine values.

Leontiev and Nietzsche

Much of the reception of Leontiev, especially outside of Eastern Europe, is tied up with parallels between his thought and that of Nietzsche. Leontiev was, after all, widely described as “the Russian Nietzsche”, due to his aristocratic temperament, his emphasis on the will of the individual and his attachment to the idea of the cultural cycles dependent upon ethnic spirit. The pair were also joined in their rejection of bourgeois morality and materialism. Although both were writing at the same time, it does not seem either was aware of the other.

Leontiev opposed utilitarianism, instead pledging himself, in aristocratic and Romantic fashion, to the cause of aesthetics. He saw the instrumentalization of art in the service of the state and providing mere domestic contentment as the sign of a culture’s death. “The mark of dying cultures is not torment, bloodshed or suffering, but vulgarity and sameness, and these arrive at precisely the moment that a culture turns to moralism, to a deification of man’s wellbeing.“[iv] This came about because of the deracinating effect of liberalism and individualism – as well as the influence of foreigners and foreign culture – which forestalled authentic artistic expression of the vernacular and sacred in their purest forms. “The cause of this people’s debasement was rooted in a dying vitality, in weakness, faithlessness and fearfulness.”[v]

According to Nietzsche, the artist was an exceptional man, who used his powerful will to direct viewers and (ultimately, if powerful enough) the course of history. Leontiev would no doubt have agreed that only a man strong enough to stand outside the mediocritising democratic standards of the Nineteenth Century could make art of serious purpose and excellent form.

We can count them both thinkers as reactionary in position and aristocratic in temperament.

Leontiev on cyclical complexity

Leontiev, in Byzantinism & Slavdom, elaborates on the idea of cultural cycles, where he draws as parallels between the life course of animals, plants, men and civilisations. He applies a Darwinian view to the culture, stating that (like flora and fauna) cultural systems grow, undergo stages of change including complexification and simplification, then become weak, deteriorate towards homeostasis (not a word he actually uses) and entropy, before dying and its component parts dissolving. Clearly, Leontiev’s early training in medicine had a hand in his thoughts regarding mankind’s nature, regardless of his commitment to the truth of Orthodox Christianity.

Darwin’s theory of evolution is apparent in Leontiev’s explanation of the way civilisations develop from a simple stage to a complex system, which comes from a kernel that contains its destiny, found in its genes. All civilisations go through the same life cycle but find different expressions because the peoples have divergent characteristics, with each making its culture in its own image.

Leontiev describes the development of various civilisations in a brief manner, nominating particular eras as indicative of phases common to higher cultures. He also attempts to discern when a civilisation becomes distinct from its founding pioneers and takes on unique characteristics. He calculates that Babylonian and Assyrian civilisation lasted “twelve centuries, the same as Classical Rome, an eternal example of statehood”.[vi] Byzantine civilisation lasted 1128 years, by his sums. The abnormal longevity of China and Egypt may be explicable due to the existence of discrete consecutive civilisations of 1000 to 1200 years duration, which scholars may yet distinguish.

Among animals and societies, growth is followed by complexification, which is the opposite of spreading – which is merely the distribution of homogenous components or quality – and that there is hostility between development and expansion. In a vivid piece of description, Leontiev tells us that death is a process of simplification. “Everything gradually merges in the corpse, seeps out, liquids congeal, dense tissues loosen, all the hues of the body merge into one greenish-brown. […] Then, the simplification and merging of components continues toa greater extent, through the process of decomposition, decay, dissolution and leaking into the environment.”[vii]

In a striking passage, Leontiev (in a condemnation of “progress” as a physiological process) characterises late-stage cultural decadence as a bio-mechanical situation, which we might relate to cultural relativism and aesthetics of Modernism and Post-Modernism.

“The phenomena of egalitarian-liberal progress are similar to the phenomena of combustion, decay, melting ice […]; they are similar to phenomena such as, for example, the cholera process, which gradually turns very different people first into more uniform (equal) corpses, then […] skeletons and, finally, into […] nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, etc. […] With all those processes of decay, combustion, thawing, cholera and the progressive movement, the same general phenomena are noticeable.

“A) The loss of features that distinguished a hitherto despotically formed whole trees, animal, fabric, crystal, etc. from everything similar and neighbouring.

“B) Greater similarity of the constituent parts than was formerly present, greater internal equality, greater uniformity of composition, etc.

“C) The loss of the formerly strict morphological outline: everything merges, everything is freer and smoother.”

As tradition is dissolved by liberalism, so recognisable time-honoured forms are dissolved by egalitarianism, the suspension of rules and the reservation of condemnation (and even judgement), consequently forms lose their distinctiveness. There is the urge to innovate and hybridise, with a subsequent reduction in purity and separation. As regionalism, caste, class and ethnic difference are eroded – and individuality is diluted by (paradoxically) the creed of individualism and egalitarianism – so a society is no longer capable of its former cultural achievements. Leontiev’s Law, namely that greater equality in any field ultimately leads to homogeneity in that field, seems to hold true for people, social forms and cultural material.

Aesthetics and morality

Leontiev’s revulsion regarding cultural change motivates his detailed analogy comparing social progress and the decay of a body. This view has moral inferences. Leontiev sees political liberalism as destruction of a healthy autocratic system, where the dignity and necessity of division and distinction by class, trade, status and form is dissolved by the poison of egalitarianism. Egalitarianism tells a serf that he can be a free man and a teacher that he can be governor. It liberates the atoms of society, inciting pointless, destructive movement, which ruins the complex system which has evolved to find use for all and allowed the great to flourish and the small man to play his part. Just as the machine will fail when its components refuse their allotted roles, so society disintegrates when social mobility allows individuals to break bonds of heredity.

For Leontiev, the morality of aesthetics is related to systems being allowed to develop naturally to their fulfil their destiny. Discord in physical culture is a sign of disease, poison, contamination which springs from socio-political causes. That discord may take the form of anaemic homogeneity due to the influence of Western materialist secularism and democracy, which degrades the traditional form and trade, where reverence for material, method and style is depleted by social mobility, foreign influence and lack of respect. Although Leontiev does not mention it, he probably felt as Ruskin did that mechanisation and industrialisation added to the spread of uniformity and divorced the maker from his craft. The artisan was replaced by the factory worker.

In short, aesthetics is not only a foundational part of civilisation, it is also an indicator of the health of that civilisation, with the morality being implicit and indirect. However, from a biological point of view, Leontiev considers decline and death inevitable. He sees Slavdom as no different from other cultures and offers no hope that Slavdom may be preserved beyond its natural term. In that respect, he is closer to Spengler’s profound pessimism than to Nietzsche hope for the revitalising influence of great men as lawmakers, warriors and artists.

Leontiev’s numerous literary works exist in English in the single book here discussed. There is a need for other publications in translation, especially a collection relating to aesthetics and culture, as Leontiev’s ideas regarding those subjects are split between books, articles and letters. Let us hope Taxiarch Press (publisher of Byzantinism & Slavdom) makes available to English-speakers more of Leontiev’s thought.

Konstantin Leontiev, K. Benois (trans., intro.), Byzantinism & Slavdom, 2020, Taxiarch Press, Zvolen, Slovakia/London

[i] P. 5

[ii] P. 2

[iii] K. Benois, p. ix

[iv] K. Benois, p. x

[v] K. Benois, p. xi

[vi] P. 105

[vii] P. 82

thank you, picking up a copy now

An interesting thinker I'd never heard of before! I shall come back to this again.