Baudelaire: Scandalous and Impoverished in Belgium

A new translation of Baudelaire's last writings gives us an insight into a desperate man.

By 1864 Charles Baudelaire (1821-67) was at the end of his tether. Depressed, humiliated, full of spleen, he was in Brussels – a place he despised. He had come to give lectures, having lost inspiration for writing poetry, tired by illness and poverty. As he struggled to gain contracts for his verse, he wrote notes venting his spleen about the Belgians. The glory and notoriety of his early years seemed long behind him. A new volume of translations brings us Baudelaire’s fragmentary ideas, full of anger and bitterness.

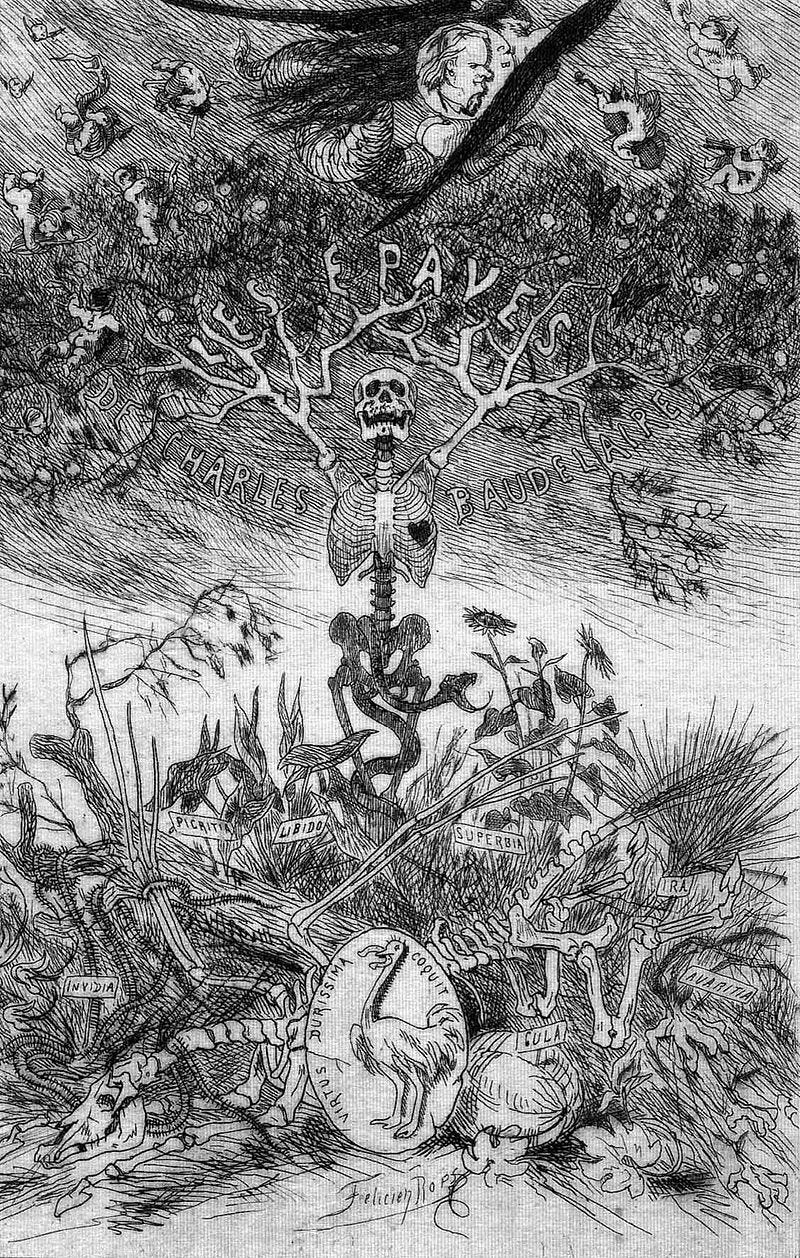

The complicated publishing history of Les Fleurs du mal (first edition 1857; second edition 1861), the primary volume of verse by Baudelaire, does not need to be elaborated much here. It was essentially the core body of his verse from his early maturity to close to his death, published in two editions, with a third one planned. The first version was prosecuted for blasphemy and outraging public morals. The judge ordered that six poems be banned and these had to be left out of the second (expanded) edition. The third edition was never realised (nor its contents fixed by the poet) in Baudelaire’s lifetime. His book of Belgian people and culture (under the title La Pauvre Belgique! (Poor Belgium!)) remained in note form only. Quite reasonably, without publication offers, Baudelaire had no incentive to write longer prose, so the Belgian material was not completed. Late Fragments: Flares, My Heart Laid Bare, Prose Poems, Belgium Disrobed brings together Baudelaire’s last writings in translation, with extensive commentary. This collection presents the late writing, omitting textual repetition that occurred in Baudelaire meandering stream-of-conscious notes.

Baudelaire lived under the humiliating restriction imposed by a conseil judiciaire, who controlled his finances. The youthful poet had shown his profligacy by spending on luxurious clothes and art, as well as running up debts, hence his mother was persuaded to petition the court to appoint (in 1844) a guardian to prevent her son from accessing the remainder of the capital of his paternal inheritance. Such monitoring and controls rendered the poet a supplicant and demeaned him, rousing him to bitterness and fury, which he periodically launched against his mother and stepfather.

Disagreeable and afflicted by bouts of lethargy, Baudelaire had alienated the many journal editors willing to commission articles by the talented critic and essayist. He sometimes had reasonable complaints about editors altering texts without approval and was meticulous about correction and typesetting of poems. Irked by the ignominious drudgery of writing articles rather than receiving the riches that his poems should be garnering, Baudelaire spent hours debating ideas that never made it on to paper. He eked out small sums by selling prose poems to multiple journals without informing the editors that the material offered had already appeared elsewhere. Little reviews accepted poems but folded before they could publish anything. Auguste Poulet-Malassis (the soft-hearted publisher of Les Fleurs, convicted and fined for publishing poems that outraged public morals) was going bankrupt in slow motion and was seeking to recoup loans made to Baudelaire (among others).

Baudelaire was not necessarily indulging in the vices he described in conversation and prose but was pleased to have others talking about him as debauched. Baudelaire was actually very concerned that narcotics “were one of the greatest dangers to the ultimate salvation of man, that they were one of the most powerful and enticing temptations of the devil.”[i] The elation of sensual ecstasy is accompanied by remorse, obloquy and damnation. This view was reinforced by the experience of translating into French Thomas de Quincy’s Confessions of an Opium Eater. For the creative man, intoxicants destroyed his vital potency, diverting him, reducing his will, ruining his concentration. This argument was made by Baudelaire in his book Artificial Paradises (1860).

Despite the positive reception of his Poe translations and the notoriety of Les Fleurs, Baudelaire received relatively little income from book sales.[ii] His once fine clothes were threadbare by the early 1860s and hung loosely on his malnourished frame. He was indeed a poete maudit, even (in 1861) considering suicide to end his despair. He implored his mother to pay off his debts and help Jeanne Duval, his prostitute mistress, live independently from him, as he realised the cursed nature of their relationship, which brought them no happiness by the late 1850s. In his last years, wracked by remorse, Baudelaire sought redemption and enlightenment in religion.

In order to gain relief from the pressure of creditors and to earn some money, Baudelaire decided to embark on a lecture tour of Belgium. In order to defray the cost of travel, Baudelaire applied to the government for a grant. (Overture refused.) He arrived in April 1864. His lectures did not go particularly well and were not lucrative, but rather than cut his losses and return to Paris, Baudelaire decided he could not return until he had attained either esteem or a goodly sum. In effect, that just extended his stay in a city he found dull, inhabited by people he considered uncultured.

This rubbed off on him. “One becomes Belgian for having sinned. A Belgian is a hell unto himself.”[iii] The bitterness, uncertainty and effect of syphilis upon his brain had left him much diminished. Poulet-Malassis noticed this deterioration. “Baudelaire’s flaws – his procrastination, his obstinacy, his ramblings and ravings – have reached such a proportion that it would be more than a little tiresome to have him over on a daily basis. His studies consist if making everything fit into his preconceived ideas.”[iv] Baudelaire described the distressing symptoms that afflicted him. “Fits of suffocation. Horrible headaches. Heaviness; congestion; total dizziness. If standing, I fall; if sitting, I fall. All this quite rapidly. After regaining consciousness, the need to vomit. Head heating up. Cold sweats.”[v]

In his years in Brussels, Baudelaire’s ambitions shrank to finding a reliable publisher who might provide him with regular income. He wrote to his mother, “I no longer dream of making a fortune, but only of paying my debts, and of being able to produce a score of books which will me a steady income.”[vi] Simply making a living by writing and having his books come out in a timely fashion were his goals, as his health faltered. He tried to sell the rights to his poems. As a small publisher deliberated, Baudelaire sank deeper into debt, adding his liabilities in Belgium to the outstanding ones in France. Appalled by the debts, even his sympathetic and upright conseil judiciaire advised him to slink away from his lodgings. Syphilis, contracted in his youth, eventually crippled him in 1866, rendering him bedridden and speechless. He returned to Paris only partly recovered and died in a Paris nursing home in 1867.

Retrieved from his writing trunk after Baudelaire’s death were various manuscripts, notebooks and letters. These were Flares (1855-6), Hygiene (1862 (and 1865?)) and My Heart Laid Bare (1859-65), texts that were combined as the basis of the book known in English as Intimate Journals. In addition, this new volume gathers prose poems and notes about Belgium. Baudelaire experienced chronic lethargy resulted from illness and use of opium and alcohol. It would be fair to consider the practice of working in fragments as due to the writer’s lapses in concentration and energy but also a conscious aesthetic stance. Likewise, the production of prose poems – a form which it seems he innovated in 1857 – needed no more sustained effort than the verse he decided not to write, but it required less sustained inspiration.

These prose poems are halfway between verse and stories. They offer snippets of a larger world without offering much exposition outside of the immediate actions. We are given little context or history. A man at a shooting gallery thanks his wife for inspiring his aim when he shoots the head off a doll, which he imagines as her. A scholar beats up an old beggar for asking for alms, only for the beggar to beat him back. A meditation upon dogs notes how the Belgians harness dogs to pull carts. “Have you visited lazy old Belgium, and have you admired as I have all these energetic dogs pulling the carts of the butchers and milkmen and bakers, all barking in jubilation, all expressing the pleasure and pride they feel in competing with workhorses?”[vii] In an unfinished draft, Baudelaire imagines himself inhabiting (and actually being) a tottering ruin. “I forever inhabit a building about to collapse, a building attacked by some secret disease. – Just to amuse myself, I mentally envisage to what extent this stupendous mass of stone and marble, with all its statuary and walls about to crash down into each other, will be besplattered by human brains and body parts and shattered bones.”[viii]

The pithy notes that comprise Baudelaire’s late writing are a conscious extension of Poe’s Marginalia, which he had read avidly in the first edition of Poe’s collected works. Baudelaire damned women as sources of distraction, draining men of ability from the capacity to act. “[The typical man] wants to be two. The man of genius wants to be one, hence solitary.”[ix] Baudelaire’s sour view of women takes has civilisational import. Women’s influence, and man’s bestial sexuality, divert men from higher deeds.

Pre-empting Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) by over three decades, Baudelaire declares “The masses adore authority,”[xi] and that the weakness of the Church derives from its femininity. He also comments that “It is only despite themselves that nations produce great men – like families. They make immense efforts to have none at all. That is why any great man needs, in order to exist, to possess a striking force far greater than the force of resistance developed by millions of individuals.”[xii] Tantalisingly brief, those three sentences stand alone. The most plausible extension of Baudelaire’s argument is that states seek to maintain themselves by keeping their populations docile through lack of heroic individuals, for it is the hero who can exert will to change society and overturn the ruling clique. Through education, the blunting effects of materialism and the culture of the masses, the state neuters her most brilliant and potentially dangerous subjects in order to protect her rulers and sustain continuity.

We find the author’s other reactionary stances in the aphorisms. These include opposing democracy and supporting the death penalty. (He supported the death penalty for misspelling – not entirely in jest.) He dismisses materialism and liberalism. “The belief in progress is a lazy man’s doctrine […] The only true (that is, moral) progress that can take place is in the individual and by the individual.”[xiii] T.S. Eliot wrote, “He rejects always the purely natural and the purely human; in other words, he is neither ‘naturalist’ nor ‘humanist’.”[xiv] He places his faith in pre-Enlightenment thought. “The only reasonable and stable form of government is the aristocratic one.”[xv] “Superstition is the reservoir of all truths.”[xvi] He admired John Wilkes-Booth’s brave end, resisting apprehension for the assassination of President Lincoln.

His thoughts on Belgium were unremittingly negative. Everything was dirty, crude, imitative (of the French). “The vegetation is quite black. – The climate is humid, cold, hot, humid, four seasons in a single day. – Not much animal life. No insects, no birds. Even the beasts flee these accursed climes.”[xvii] He hated the loudness of Belgium. The cobblestones were loud under shoes and wheels; the Belgians whistled incessantly. It was strange that there were “Many balconies. Nobody on the balconies. Nothing to see on the street.”[xviii] It was absurd that of the pince-nez sold, most were fitted with plain glass, not lenses, and sold only as a fashion accessory.

Belgians are so ungainly, they “have no idea how to walk. They fill up the entire street with their arms and feet.” Belgians are ugly, without even human faces. “Formless, deformed, rough, heavy, hard, unfinished, carved by knife. […] Some of them display monstrously thick tongues, which accounts for their slurred, sibilant speech.”[xix] As Baudelaire takes his complaints to parodic lengths, the people around him become monstrous caricatures.He considered Belgians untrustworthy, stupid and unwelcoming. Ultimately, circumstances turned Baudelaire into what he hated – an honorary Belgian: unhealthy, bitter, mistrusting, harsh, petty, obsessed by money. Like a character in one of Poe’s stories, he had become a damned avatar of his nightmares.

Among the insults and comic sketches – a man eats a living dog at the circus, hopefully a caprice rather than a report…. – there are comments on art and architecture, some admiring. Yet overall, it is violent derision that remains the overwhelming impression of these Belgian notes and the last prose poems. As an insight into a failing mind, akin to Maupassant and de Nerval’s deterioration, Baudelaire’s late writings It is no surprise that even admirers of Les Fleurs found Baudelaire’s last writing de trop. Among his critics were not only old foes such as Victor Hugo but later writers André Gide and Jean-Paul Sartre. Supporters included Leiris, Bataille, Blanchot, Eliot, Isherwood and Auden. A close reader was Nietzsche, who (reading in 1888) found much to admire in Baudelaire’s late ideas. “Reading Baudelaire, Nietzsche was inspired not just to quote him but to rewrite him, the seventy pages of his notebooks sometimes reproducing the original French, sometimes refracting it into German, and sometimes oscillating between the two languages within the space of a single sentence or passage.”[xx] To Heraclitus, Nietzsche added Baudelaire in his pantheon of great writers of the aphorism.

In a forthcoming article, I shall explain the aesthetics that Baudelaire that took from – and elaborated upon – those of his hero Edgar Allan Poe.

Charles Baudelaire, Richard Sieburth (ed., trans.), Late Fragments: Flares, My Heart Laid Bare, Prose Poems, Belgium Disrobed, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2022, 427pp + viii, hardback, £20/$30, paperback available, ISBN 978 0 300 185188

Charles Baudelaire, The Flowers of Evil, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008 (1993)

Enid Starkie, Baudelaire, Pelican, London, 1971 (1957)

William Rees (ed., trans.), The Penguin Book of French Poetry 1820-1950, Penguin, London, 1992 (1990)

T.S. Eliot, Selected Essays, Faber & Faber, London, 1939 (1932)

[i] Starkie, p. 440

[ii] “It is estimated that Baudelaire’s lifetime earnings from his literary work amounted to 14,000 francs – 9,000 coming from his translations of Edgar Allan Poe and 5,000 from his original works – roughly the equivalent of the salary that a midlevel bureaucrat of the period would have earned over three years of employment.” Sieburth, p. 6

[iii] Sieburth, p. 20

[iv] Quoted, Sieburth, p. 25

[v] Quoted, Sieburth, p. 27

[vi] Quoted, Starkie, P. 568

[vii] Sieburth, p. 197

[viii] Sieburth, p. 208

[ix] Quoted, Sieburth, p. 56

[x] Quoted, Sieburth, p. 55

[xi] Sieburth, P. 82

[xii] Sieburth, p. 86. See also, “Nations produce great men despite themselves. The great man has therefore reaped a victory over his entire nation.” Sieburth, P. 117

[xiii] Sieburth, p. 117

[xiv] Eliot, p. 385

[xv] Sieburth, p. 120

[xvi] Sieburth, p. 114

[xvii] Sieburth, p. 289

[xviii] Sieburth, p. 300

[xix] Sieburth, p. 302

[xx] Sieburth, pp. 64-5

[xxi] Starkie, p. 625

[xxii] Sieburth concurs.