Bad Painting, Folk Art and localism

Localism is an antidote to internationalist avant-gardism. But what would localist art look like? Possibly strange, wonderful and awful.

Say you want to counter a trend which is reducing fine art to a cycle of cautious, state-approved bromides that defang art and undermine national identity. What happens if that opposition works…but you end up with art that might be just as bad?

If we define ourselves in negatives, by identifying what we reject – as so many emerging groups or movements do – we will likely find ourselves in uncharted territory. For example, let us say that we oppose the globalised art market as a framework for producing new art. Globalist art’s expansion and hegemony – as measured at the highest strata of publishing, selling, exhibiting, museum acquisitions and auction prices – is antithetical to the development of art that answers to the axiomatic principles of truth, beauty and joy, and which is non-egalitarian and non-utilitarian in character. The opposite of globalist art is localist art. That is what I have previously advanced as an alternative to state-directed state-serving art. After all, in the absence of a realistic prospect of securing control of central power, one must oppose it and find routes to cultivate new art of value. The best way to oppose centralised dissemination of cultural material intended to undermine national customs is to encourage a decentralised localism that can sustain itself without central control. And the outcome of that localism would be…. well, what exactly?

The case of localists is that if the malefic globalism avant-garde has its grip on the consciousness of the country loosened, a population of artists – once free of top-down direction – will naturally gather into nodes of regional, national or ethnic identity. The pull of authentic subjects will draw artists together in common cause. Yet, is that really what would happen? In a society so deracinated – that is, literally, “unrooted” – is there any Volksgefühl still extant which could manifest?

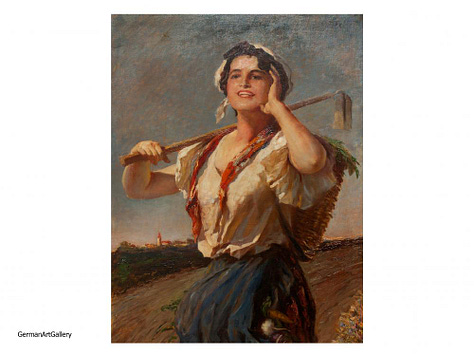

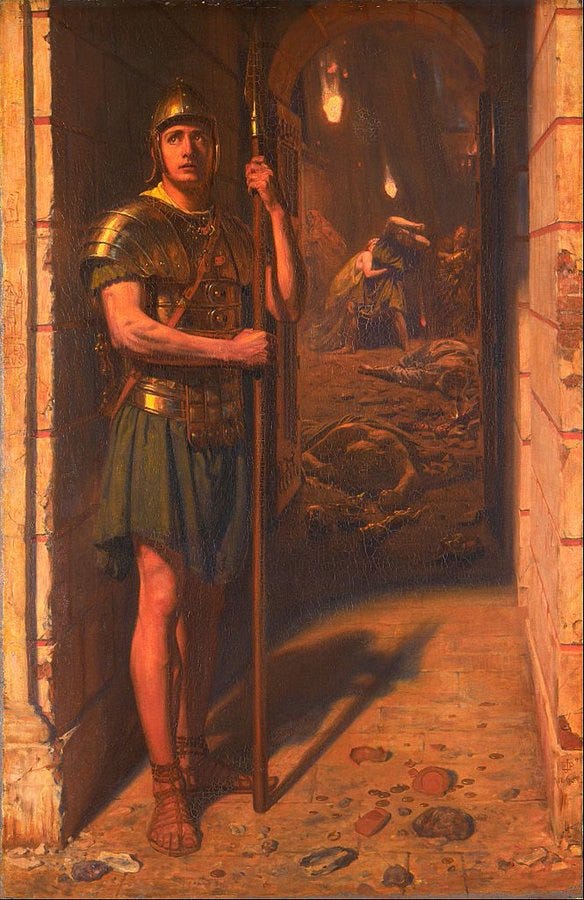

There are no shortage of artists and commentators agitating for regional and national schools of art that might provide an alternative to the art of Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Richard Prince, Anthony Gormley, Yue Minjun, Yayoi Kusama and other brands one finds cluttering up the museum and art-fair schedules worldwide. As debates rumble on about exactly how the shoddiness of the modern world is to be confronted and remediated in all areas of culture, we have seen a resurgence of support for traditional painting. This tradition is of a limited kind and centres upon the art of French Naturalists, academic German Romantics, Victorian salon painters, Impressionists, Art Nouveau and fantasy art. Common subjects are women in meadows, children in traditional dress, heroic men, pristine wildernesses, wild animals and so forth.

The art these objectors make or recommend looks conventional and laboured. Would galleries full of new art of this type inspire in a discerning visitor anything other than disappointment? Wouldn’t a viewer want something more ambitious and (not in a modish way) of his own time rather than strategically timeless? I have already expressed my doubts about this here.

Let us say a genuinely decentralised culture emerged and was allowed to flourish. What sort of art would arise among the next generation, freed from the grip of liberalism and Post-Modernism? What would the blossoming of a new Folk Art – made by local people, arising from local needs, embedded in the lives of people detached from metropolitan mores and civil-service diversity quotas – look like? The answer may not appeal to you.

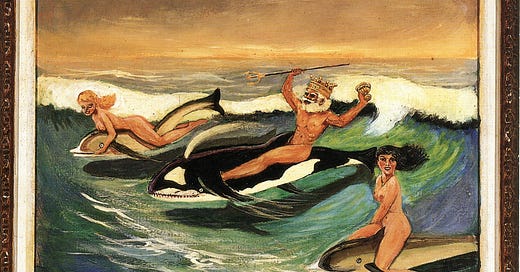

Recently I visited H MKA, the Antwerp museum of contemporary art, where I saw Jim Shaw’s current exhibition The Ties That Bind (16 February-19 May 2024). That includes his collection of amateur paintings bought at flea markets and junk shops. These Thrift Store Paintings have been exhibited widely and published, usually without data on the artist, title or origin of individual pictures. The art is a mixture of portraits, fantasy, erotica, pin-ups, decorative abstraction, Americana. Terrible Surrealism, rip-offs, faux naïf and appalling montages dominate. Anatomy is wayward, faces asymmetrical, poses stilted, landscapes garish, colours clashing. In cheap frames, crudely painted and ghastly in every way, they form a riot of bad taste. Hung edge to edge, the paintings are intended to be a spectacle, an experience, rather than seen in isolation.

The Thrift Store Paintings have a raw energy and genuine engagement that we cannot find in the high art exhibited at prestige venues. At the same time, consuming low art any quantity – unavoidably so, in the H MKA display – leaves one with a sense of emptiness. It is like eating too much confectionary. It has little nutritional value, leaves you unfulfilled and will give you a headache; in the long run, it will numb you and make you ill. Yet it has the spark of real enthusiasm, not tempered by the expectations of audience, market and history.

The Thrift Store Paintings are gruesomely funny; we are supposed to laugh, which (if we know anything about taste and culture) we do. Yet, the Thrift Store Paintings are actual living Folk Art. Staring dazedly at the freak show of bad art surrounding me, it occurred to me that the future of art in a post-internet, decentralised, populist universe would look a lot more like the Thrift Store Paintings than any 21st century Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Rather than a nativist culture that most perennial traditionalists and reactionaries expect would grow organically, we would see the rise of Thrift Store Paintings.

Folk Art is essentially an untutored composite of found images and meaningful subjects produced for a local audience, usually for little or no money, made for pleasure and not shared outside of a narrow geographical area. It is detached from fine art, as it is not made with the expectation of wider cultural reception nor is it tied to the conventions of high culture. In the age of the time-lapse videos of artists creating a giant photorealist drawing of a lion’s head or a trompe l’oeil glass of water (videos distributed instantly and universally on the Internet), where is the space for an artist to grow up ignorant of Western artistic conventions of proficiency? Why should today’s Folk Art look anything like the seascapes of Alfred Wallis? How could it? In truth – as I noted in my article on Nikos Pirosmani – Folk Art has always been contaminated by mechanically reproduced images, from playbills to penny papers and banknotes. True isolation, if it ever was, is no longer feasible in an internet age.

This is the crisis of localism. Localism is an approach which many people (including myself) have championed as an antidote to globalism and the proliferation of State Art production. If localism were to gain ascendancy, we would get a tidal wave of dreck, more modern than ancient. There would be more Cardi B than King Arthur, more memes than Medievalism, more nostalgia for Wimpy than wassailing. Demographic change, cultural depletion, expansion of Americanism and the hijacking of national symbolism have been so complete that any opening up of culture will likely result in an art (undirected by an elite) consisting of a broken vernacular of foreign pop culture and half-remembered liberal shibboleths. It would be an inadvertently Post-Modernist kind of Folk Art.

Folk Art is close to Bad Painting, a moniker which was coined in 1978 and a significant movement during the 1980s and 1990s. It is characterised by the intentional use by professional artists of devices, styles and content common to amateur and outsider art. The rise of this coincides with that of Post-Modernism and one can see Bad Painting as a strand within Post-Modernism’s playful-cum-exploitative appropriation of another distinct artist lexicon. The difference between Folk Art and Bad Painting is self-awareness. Perhaps Bad Painting (as a canny, high-status variant of Folk Art) will become the national style in a decentralised national culture.

If we want artists to paint nature, we need to be teaching youngsters the difference between a chaffinch and a corncrake. At the moment more teenagers could give you a detailed break down of seasons of an anime but couldn’t tell you the difference between an oak and an ash. The groundwork for a new art based on local knowledge and pride has not been done. Today’s artists who emulate Renaissance portraits have never worn a suit of armour nor handled a sword; perhaps they have only never seen them in real life. I’m not arguing that we should return to an agrarian age and foreswear use of the internet to make local art truly local. What I am arguing is that in the foreseeable future, our deracinated hybrid culture will (and already does) give rise to Folk Art that is full of pop culture, foreign influence, borrowed idioms and political banalities. Whether or not you find that prospect any worse than our current state, is a matter for your taste and convictions.

An art locked into a imperviously varnished Victorian historicism does not seem the product of a living culture but the product of a political stance. However much I might be sympathetic to the politics of traditionalists, I can’t see historicism as a viable path for ambitious artists or a living culture. I appreciate a well-painted still-life as much as the next man but I need more than that. I don’t know what I do want – outside of what I myself make – because I haven’t yet seen it.

Localism may or may not undermine globalism but the art it will produce will range from the academic to Folk Art to Post-Modernism. Rest assured, like the art of most ages, much of it will be pretty bad. We will just have to hope that really great artists of tomorrow will find a way of making something original and powerful that speaks of its age and speaks to the ages. That said, localism may still be the best option available. Just be prepared for an outbreak of craft and some freshly made velvet Elvises.

I think the solution is quite simple, actually, and it came to me when I was listening to a fascinating podcast episode on art in North Korea. Contrary to popular Western perception (including mine before listening to the podcast) North Korean art isn't all crude propaganda (though I actually quite like their propaganda posters, and on a purely artistic level they're infinitely better than any 'real art' being made in the West, and on an ideological level their propaganda is actually more honest, more coherent and less noxious. And they have the decency to call it what it is)--in fact they don't consider propaganda posters art at all; it's their equivalent of advertising.

Actually North Korea has a deep and thriving artistic culture. Rather than adopting foreign styles (including all modern and postmodernist atrocities of anti-art) they have instead (because they have no choice) turned inwards, deepening and refining their own indigenous artistic traditions. An example is the traditional 'Chosonhwa' ink-and-brush on rice paper painting, which North Korea has innovated by adding colour and boldness (traditional Chinese, Japanese and South Korean inkwash paintings are black and white and extremely subtle).

There are innumerable highly talented artists in North Korea (which houses the largest art studio in the world --Mansudae, basically a self-contained miniature city-cum-college campus for artists) and they work in a wide variety of styles, but all traditional and representative in form and patriotic and traditional in theme.

And they don't resent this, either. They're not being forced to do it. They genuinely want to produce patriotic and traditional art. They don't yearn to indulge in abstract subversive abominations. When North Koreans have been shown modern Western art, they simply laugh at it. Not out of knowing contempt, but sheer innocent amusement. They simply can't understand it, or why anyone would want to paint that way.

And one's selection to treat subjects of national significance -- anything related to the nation, the state, national history and so on--depends directly on your skill. Only the most skilled artists in the country are allowed to paint the Leaders, for instance. Thrift store artists, though I'm sure their equivalents exist in the North Korea, or would if they could afford paint, brushes and canvas, have no access to artistic materials or training or a public platform and are simply not allowed to depict anything with political or ideological significance. And there simply aren't any North Koreans sick enough in the head and soul to want to produce anything like the 'art' that stinks up all our Western art galleries.

Localism and subsidiarity is something I too support in principle, but in practice we are dealing with a a population and a culture so totally depraved (in the proper Calvinist sense of being corrupt in every part, not as corrupt as it conceivably could be), mass and elite, high and low, that a long period of strongly centralised control will be necessary to purge the rank infection that has overtaken us. Our collective moral and aesthetic compasses are so irreparably broken and inverted they will have to be completely smashed before they can be reoriented to point to true north again. Think of it as a period of intense weeding before the garden will be able to bloom naturally once more. It will take a great deal of discipline before we can once more learn how to be free--and can be trusted with the freedom we have earned--trusted not to destroy ourselves again. Just like a driver who's nearly driven himself and his whole family off a cliff will need a great deal of retraining and tests before he can be allowed behind the wheel again.

Wonderful article. Thank you for sharing it.

I thought of: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaret_Keane