Art critics v. the intellectual artist

The current exhibition of R.B. Kitaj prompted me to think about the territory of intellectualism in art.

When the retrospective of R.B. Kitaj (1932-2007) opened at the Tate Gallery in 1994, he was a cult artist in London. Known as an confrere of Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and other painters in London from the 1960s onwards, Kitaj was an American immigrant who noted for his eclecticism. Alongside David Hockney, he was seen as a key influence on the Pop Art scene in London during that period. Kitaj was the first to the name the specific painters the School of London – Freud, Bacon, Michael Andrews, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff, Howard Hodgkins, himself and (in some accounts) Hockney – as a discrete group. Out of this group, he was the only artist committed to recording his ideas at length in writing.

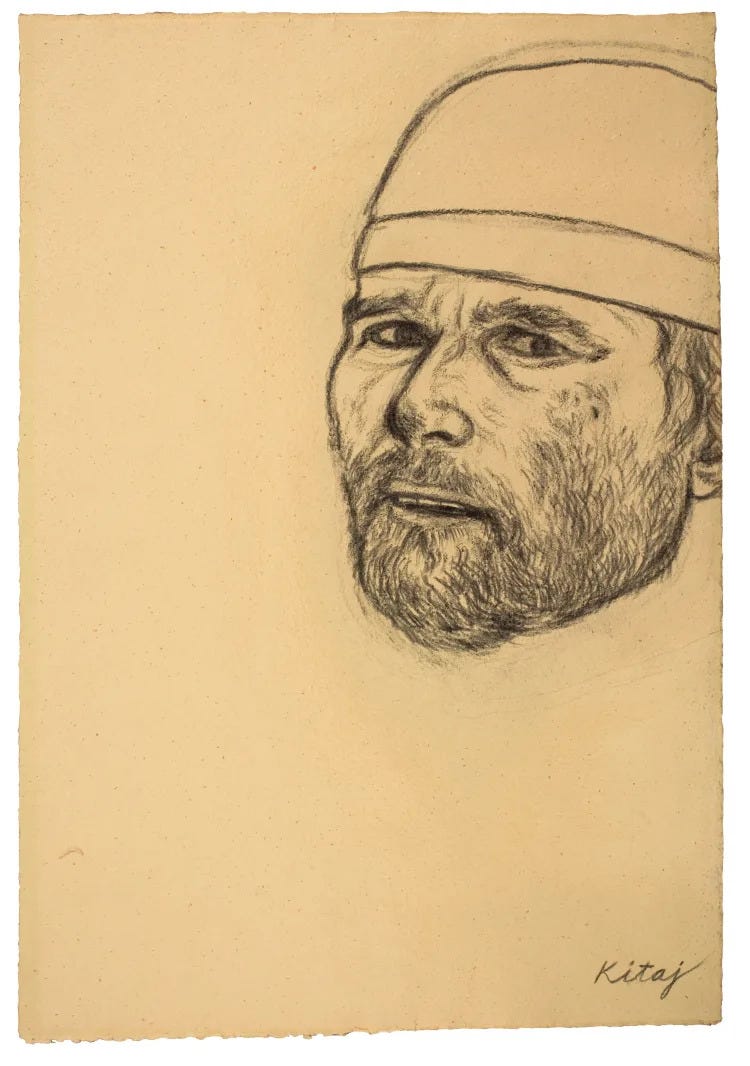

Kitaj had an oeuvre that included paintings, prints, drawings and pastels. It was these pastels in particular that earned great admiration from the cognoscenti. By 1994, he was considered a senior figure and a draughtsman of some distinction. This skill can be seen in a newly opened exhibition – R.B. Kitaj: London to Los Angeles, Piano Nobile Gallery, London, 23 October 2023-26 January 2024 – prompted me to think again about Kitaj and the fate of his Tate retrospective.

While some critics praised Kitaj’s abilities and admired his ambition, others lambasted it. Specifically, the latter singled out Kitaj’s intellectualism as a fault. For his allegories and portraits of intellectuals, Kitaj had written label texts with extensive allusions to challenging, even abstruse, literary sources, which critics took against. In the run up to the exhibition opening, Kitaj had given some interviews that were considered as bellicose and self-righteous. One summary read thus:

“Richard Dorment (Daily Telegraph) complained that, 'His explanations are so cerebral . . . that I began to feel assaulted by the overbearing ego of a man who can't imagine how his every thought could fail to fascinate me.' William Feaver (Observer) wrote: 'Many of the paintings here are curiously arbitrary, line and colour laid on like orders received.' Tim Hilton (Independent on Sunday) remarked: 'Kitaj is an egotist, and at his best when giving interviews.' The Independent's own critic, Andrew Graham-Dixon was the most scathing: 'In the absence of any apparent emotional drive to create pictures, Kitaj has spent his life concealing an absence, a lack in himself . . . The Wandering Jew, the T S Eliot of painting? Kitaj turns out, instead, to be the Wizard of Oz: a small man with a megaphone held to his lips.'”

Kitaj was seen as pretentious and domineering, guiding viewers to interpretations that the art was not strong enough to do visually. The critics’ attacks were particularly personal and Kitaj (and some of his ardent supporters) took them in such a spirit. Kitaj, who made a big play of his Judaism and his comradeship with various Jewish Modernist intellectuals, saw the dismissal as being anti-Jew. Many neutrals considered the bad reviews as not so much anti-Jew as resentful of a foreign artist (albeit one long established in London) who saw himself as better than his critics. The fact Kitaj may actually have been better read than his critics did not help matters. Most of all, it was clear that the critics disliked the idea of the artist as intellectual. They could deal with Conceptual artists referring to French Deconstructivist theory or Feminist political doctrines, which are easy enough to understand superficially and engage with just as superficially – from both the points of view of artist and critic – but a painter coming along with a ream of texts by mid-century philosophy and poetry that one had to have read was de trop.

It was an unexpected eruption of discord in an art world that ran on consensus. At the time, the old guard was slipping away from museums and publishing; the rise of the Young British Artist movement was sweeping away connoisseurship and critical scrutiny with a wave of indomitable popularity (and populism) and commercial success. Those YBAs were anti-intellectual, anti-tradition and anti-skill – the antithesis of Kitaj and his elaborate responses to the long history of Modernist theory. Gavin Turk, Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas would never trouble newspaper art reviewers about Isaac Babel, Martin Buber, André Gide and the New Viennese Art History School, the way Kitaj did.

The aversion to intellectualism was such that sceptical critics could not admire Kitaj either on his own terms or just as a craftsman or image-maker. Looking at the examples in the current exhibition – judged from the catalogue – we can see Kitaj very distinct approach to drawing and painting, which overlap. Kitaj used charcoal and paint (in early years, at least) in a similar manner, applying it drily on a textured surface and building shading gradually, with heavy saturated outlines. This was something he also did with his pastels but with more blending of hues. He specialised in portraits, which suited his technique well. He was also one of the great life draughtsmen of our time. The current exhibition brings together pieces from the whole of career, from his student years at Oxford to his end in Los Angeles.

The public spats between the critics and artist continued for years and led to Kitaj leaving London permanently, relocating in California to be close to his adult son, partly spurred by the death of his wife Sandra. Kitaj became understandably bitter. His critical standing has been tarnished since then. Neither side came out of the affair well. Kitaj looked vain, thin-skinned and pompous; the critics looked petty, shallow and narrow-minded. The richness of the art on display shows that Kitaj had plenty to offer that could be easily detached from his intellectual aspirations. Yet we never ask James Lee Byars or Anthony Gormley to stop philosophising so we can just enjoy the sculpture they present, so why would it be fair to expect us to overlook the verbal aspect of Kitaj’s artistic project?

When a group of artists including me got together for The Exhibition this summer in London, we were careful not to intellectualise. We set out principles rather than a manifesto. Kitaj was not so reticent, writing several manifestoes, thick with reference to artists, writers and thinkers. We made sure our statements were short and free of references to previous instances and external authorities. We were implacable about avoiding the appearance of being intellectuals, despite having plenty of ideas. I am not sure if the example of Kitaj was foremost in our minds but I certainly had not forgotten the example, if only subconsciously.

There will always be a conflict between artists and art critics as to whom will be the authority on what art movements are and what art is successful in itself. Who will be the arbiters of art history? The tussle will continue as long as there exist the professions of artist and art critics. It is understandable that when the artist encroaches on the territory of the critic that the latter will seek to defend his pre-eminence. We can look at Kitaj’s art and wonder if Kitaj had confined himself to a few intellectual allusions what would the reaction have been to the Tate retrospective. Surely his art was good enough to carry many doubters. It was rich, attractive, full of invention and replete with powerful images. Yet, who are we to deny him his rights to expound his ideas at length in writing? I am not in a position to judge the cohesiveness of his allegories, as a lot of his sources are not familiar to me, and I suspect that complex allegories of the type the Renaissance and Baroque period made are not really suitable to audiences today. Well, of course, an artist only has to satisfy his patrons and no one else. He need not explain nor justify anything more. Kitaj’s tragedy is that he did not let his art do more of the talking; there would have been many people willing to listen.

Coda: I should add a few words about how I see the future. Every year, successful artists - i.e. those might likely to attract attention from critics who publish in a public format or through an aggregation site - grow increasingly detached from production. They become heads of small firms, where making is delegated to assistants. That could be seen as a sign of the degradation of fine art but you’ll find such practices in studios from Greek times onwards. But the difference is now that artists no longer know how to make what their studios manufacture. Everything is handled by specialists. These leaves artists the fields of invention (of ideas), promotion and brand management. Theoretically, this would leave artists more prone to dwelling on intellectual matters. The truth is the converse. As artists produce art that is more political, they simply draw on writers, activists and academics, whose ideas they can paraphrase; or rather, they can get a clever failed art graduate to paraphrase for them.

The separation of labour and skill from the successful artist’s practice should allow for greater intellectual freedom. What happens is actually that in order to keep the business running, assistants producing, dealers dealing, art biennales supplied and so forth, things become safer. Yes, the agitprop soundbites coming from Kehinde Wiley, Carrie Mae Weems, Christopher Wool, Glenn Ligon and others are the acceptable opinions of the progressive art establishment. Rather than taking a risk, these statements are placatory and signal their affiliation to State Art, artivism, social activism and so on. They signal intellectual disengagement and, as such, are the opposite of the intellectualism that questions, challenges and risks falling on its own face due to the burden of pretension.

I have been studying Kitaj's manifestos since our country's so-called racial reckoning of recent years, which was so obviously the American manifestation of Blut und Boden that the recent explosion of Jew-hatred in the West is of little surprise. We moved to the country last year to avoid the inevitable.

Kitaj was handily better-read than his critics but my sense is that his understanding of the literary and philosophical modernists was idiosyncratic in the extreme. He was a picture-maker in constant need of a subject, and read accordingly. The critics may not have been entirely wrong in suspecting a pretense, but for Kitaj's purposes it would have been fine to scavenge the philosophers rather than analyze them. The manifestos are aphoristic and declamatory. I think the question of his dubious intellectual ambitions can be safely laid aside in favor of his obvious pictorial ambitions, at which he succeeded more often than not.

As a Jew trying to orient himself with respect to the Western canon, he left behind a record that's eminently worth revisiting in the current political climate.

Really interesting article, thank you. I know a little about Kitaj. I became interested in his work after the much-lamented Late Show on BBC2, discussed the vitriolic reaction to his 1994 retrospective at the Tate. Kitaj’s wife had died shortly after the exhibition, and he directly blamed the British art critics for her death. The notion that ‘the art should speak for itself’ was pre-eminent back in the 90’s, with the success of the YBA’s. It’s hard to imagine Tracey Emin writing a ‘manifesto’ on her work. She has, however, written a memoir, ‘Strangeland’ which, given the highly personal nature of her art, is probably the same thing....