Architectural radicalism

A survey of unorthodox architectural courses introduces some fascinating examples but is limited by the outlook of the editors.

Radical Pedagogies is a survey of experiments in architectural education worldwide, all undertaken after 1945. It consists of an introduction, followed by summaries of over 100 experiments of projects worldwide. These are about 200-1000 words long and illustrated by photographs, plans, posters and other visual material. Most of these unusual teaching practices, consisting of workshops, gatherings and informal happenings, as well as more conventionally taught courses and seminars, have a political dimension. Workshops were host to developing groundbreaking ideas and technical innovations, many of which was not practical (or cost-efficient) to implement. The development and transmission of ideas and values come above designs ready for implementation.

Examples come in many forms, with different sponsors. Jean-Jacques Deluz’s course at École Polytechnique d’architecture et d’urbanisme, Algiers ran from 1970 to 1988 and was approved by the Algerian government during a period of massive spending on civic architecture for the post-colonial state, at a time when Algeria had few native architects. Deluz taught his students to build Modernistically, with attention to the specific conditions of sites and populations. The ministries found the teaching too pragmatic and variable and they curtailed the course, seeking homogeneity in future cohorts of architects. Other courses were decidedly anti-authority, such as the Barcelona course, held 1964-1975 which was seen as Catalan resistance to Franco’s regime. At exactly this time, an obsolete super-computer was used in a university department in Madrid, applying computing technology to design in order to make designing more efficient and perhaps free architects to be liberated from technical constraints. La Escuelita, run in Buenos Aires 1976-83, was conceived of as resistance. “Rather than an official institution, the school was conceived as a marginal entity, legally nonexistent. A lack of official recognition also meant a lack of official control over curricula and content, which allowed the school to operate outside the tighter constraints on architectural education in Argentina at the time. The new dictatorship viewed education activities with permanent suspicion […]”[i]

In Cuba, the Communist government built art schools upon the site of the confiscated Havana country club, pleasure palace for Batista-regime officials and mobsters. The arts, including architecture, were seen as a means of reshaping society. The influential Hochschule für Gestaltung, Ulm in West Germany was established with assistance from the occupying American armed services after World War II, going on to become a beacon for Modernism and liberalist thinking in the arts. HfG was a progressivist project, through which educators were “trying to reshape a nation across all scales “from the teaspoon to the city.” In fact, the school’s avowed ambition was nothing less than to redemocratize postwar Germany through “good design”.”[ii] This universalising reshaping ethos can be found in the conservative Arts and Craft movement, the bourgeois Weiner Werkstatte, the Modernist Bauhaus and the functionalist VKhuTEMAS, Moscow school of applied art, all of which fall earlier than the parameters of this book. The 1946-1963 course in Chile was based upon Hannes Meyer’s Bauhaus curriculum and Bauhaus influence came through former students there or publications transmitting its revolutionary ideas.

Many of the projects were either mobile (such as a British 1973 tour of a converted double-decker bus) or diffuse (the Open University in Great Britain, Global Tools’ European universities co-operation). Others were residential. Womanhouse, a mansion in Los Angeles that a group of feminists in 1972, as a development of feminist collectives and courses from the preceding years in Southern California. Womanhouse was the implementation of Marxist and Critical Theory applied through a socio-political critique, specifically directed against a society seen as oppressing women. Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, lead educator at Womanhouse and the Feminist Art Program, went on to take up a position in Yale. It is noticeable how many of the most prestigious universities were not only home the progressive courses but actually innovated and disseminated the ideas. Far from being outsider projects that swept up support organically, radical pedagogies are those implemented by the elite from high profile learning centres, where institutional authority validates disruption.

The student protests of 1968 and following years led to not only demonstrations and sit-ins but also to unconventional educational activities. One in California included a “nakedness experiment”. In 1969, Yale’s architectural department was subject to arson by radicals and draped with banners protesting the imprisonment of the Black Panthers. Architecture and the construction industry was targeted as an ally of the US military during the Vietnam War, in some peripheral manner benefiting and advancing the war effort of the military-industrial complex. MIT’s closeness to the military contractors was a cause of student unrest in 1969, causing a ripple of reaction throughout different departments.

Inter-disciplinary actions characterised thinking in universities in this period. The practice undermines expertise and allows non-experts to dilute and confuse the academic status quo, permitting them entry into the system as arbiters of new hybrid fields. In Sao Paulo, the Artigas was inter-disciplinary in that it linked architecture more to design and politics in a move to wrest architecture from the dominance of engineers. By reducing the influence of science and mathematics, architects could be more political and design in ways that were not driven primarily by logic, physics and cost efficiency. In comes as a surprise to see something similar happening in Nanking following the death of Mao and the definitive termination of the Cultural Revolution. This saw engagement with Post-Modernism, semiotics and a collaborative action painting.

“In 1986 they created a performance art piece that simulated a primitive totem ritual. The work, initiated by Qian Qiang, was inspired by a trip to Xin Jiang (a province with a minority ethnicity). Shu Wang directed the show, which ran for around ten to twenty minutes. First, three or four people (including Qian) painted primary colors (red, yellow, blue) on a huge piece of cloth at random, then Wang came in and painted totem patterns on it in Chinese ink. Finally, two people pulled up the fabric with ropes and hung it on the inner façade of the courtyard while the rest got down on their knees as part of the ritual. Because it rained, and the fabric was not absorbent, the paint all merged together and turned into a huge black painting.”[iii]

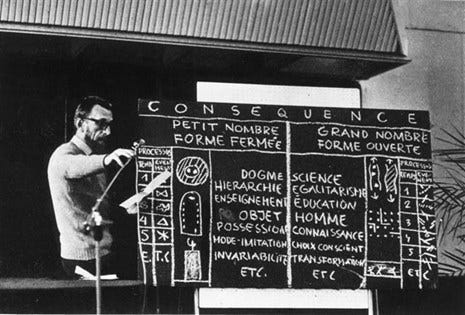

There are too many different strands to discuss in detail. We can see Modernism, Post-Modernism, post-colonialism, feminism and communitarianism underpinning certain efforts, including residential and non-institutional activities. Indeed, if one thinks of a political or philosophical movement, then there is an attempt to turn this into an architectural philosophy, action or critique. The wide variety of visual material is There is a revealing photograph of a blackboard of a lecture in Wroclaw in 1975. It shows Oskar Hansen explaining Open Form theory, a set of dualities that reflect the supposed political and philosophical oppositions that architecture – or at least architectural theory – presents.

CONSEQUENCE

small number, closed form great number, open form

dogma science

hierarchy egalitarianism

implementation education

object mankind

ownership understanding

imitation conscious choice

rigidity flexibility

The idea that openness of form is equivalent to openness of attitude and consequently an indicator of an elevated and enlightened sensibility is plain. Whether or not these dichotomies exist, this outlook is widely accepted in the Western Modernist tradition, steeped in liberal assumptions, which persists in architectural thought today.

“[N]on-conforming bodies united to question the structures of the past and to start anew.”[iv]

The editors’ introduction betrays (in political terms) limited insight. By characterising the drive for radical prioritisation of race, class and ecological issues in architecture as being grassroots in nature, the editors fall into a common assumption. They assume that the talk of social justice is backed up by the activities they describe. “Radical pedagogies sought to break free from conventional definitions of institutions. Often escaping schools or official administrative complexes, they longed to effect direct systematic change in patriarchal, colonial, ableist, or other entrenched discriminatory power structures.”[v] The truth is that these positions are championed by counter elites – academics, writers, activists, pressure group leaders, lawyers – who subvert institutions from within and adopt the supposedly radical assault from outside and turn it into a establishment position in order to destabilise the status quo. The radical proposition is used to dilute conservative position, undermine tradition and demoralise the majority population. In that way, race radicalism is co-opted by activist faculty members within institutions, just the way that the civil rights movement was bankrolled by political allies within the establishment and then effected throughout the power system and imposed upon the majority and against the majority. Outsiders have no power except where they are permitted as useful clients for the counter elite existing within positions of influence. Students of elite theory will recognise the Jouvenalian high-low axis operating when a lecturer invites a radical activist or representative of a community group into a university to host a seminar. It is the animus of the lecturer that opens the doors of institutions to outsiders with hostile intent. Non-institutional programs are means of spreading influence, building networks, stress-testing concepts and establishing non-institutional power bases.

There are no examples in this publication of architectural projects not involving either university lecturers or qualified architects. In other words, there are no projects that are not associated with or part of university training. No doubt it is harder to obtain what documentation and testimonies that exist regarding truly subversive and informal activities in architectural education. Notwithstanding the limitations of the editorial approach, there are fascinating and surprising summaries to be found in Radical Pedagogies.

Beatriz Colomina (ed.), et al., Radical Pedagogies, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2022, paperback, 416pp, illus., $59.95, ISBN 978 0 262 54338 5

[i] P. 129

[ii] P. 122

[iii] P. 152

[iv] P. 19

[v] P. 16