Alfred Kubin and the Art of Horror

In the latest part of Halloween series Art of Horror, we look at the Austrian Symbolist.

The Symbolist movement was a loose tendency involving many groups and individuals working in Europe and North America from around 1850 to 1914. The adherents believed that art had become too concerned with propriety, finish and following the tendencies towards social realism and naturalism and that art should instead be directed towards eternal stories and the most primal of human fears and desires, which could be achieved by using symbols with cultural or psychic power.

The power of horror, nightmares, suffering and terror were staples of Symbolist art, as it was in the poetry of Baudelaire and the stories of Poe. In the selection below, we take a look at some of the lesser known pieces of art by Symbolist artists. In the first part we look at the prints of Alfred Kubin.

Alfred Kubin (1977-1959)

Austrian graphic artist and author Alfred Kubin was a second-generation Symbolist. When he was an art student in Munich, he discovered the Symbolist imagery of James Ensor, Edvard Munch, Max Klinger and Felicien Rops. He produced dark fantasies of nightmares, often suffused with anxiety regarding sex and the power of women. His outlook was coloured by his readings of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer. Kubin wrote “In my desperate mood I found [Schopenhauer’s] pessimistic Weltanschauung the only correct one, and I revelled in his ideas – with the consequence that my universal discontent only grew greater.”

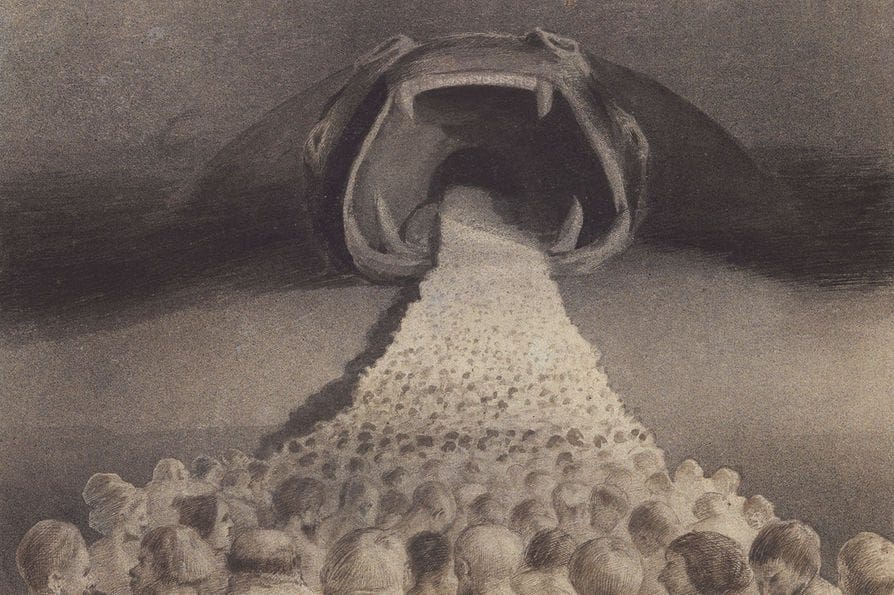

Into the Unknown (1900-1)

Kubin worked in monochrome, using ink wash and pencil to produce drawings with a dark tonality suitable to his subjects. Into the Unknown is comparable to Daumier’s famous Gargantua (1831) where people carry wheelbarrows up a ramp to feed a representation of the a tyrannically greedy aristocrat.

The Hour of Death (1900)

This drawing displays Kubin’s engagement with the macabre stories of Poe, especially “The Pit and the Pendulum”. It is the approach of horror stories that feature on the exploitation of the suffering of the victim and the sadistically devised inventions that will infliction harm upon him. In this picture, the victims wait as the beheading sword inevitably moves towards them, inexorably. Note the pouch slung underneath to catch the falling heads. Technically, Kubin uses his materials to make the scene visually lively, with the dramatic cross-hatching.

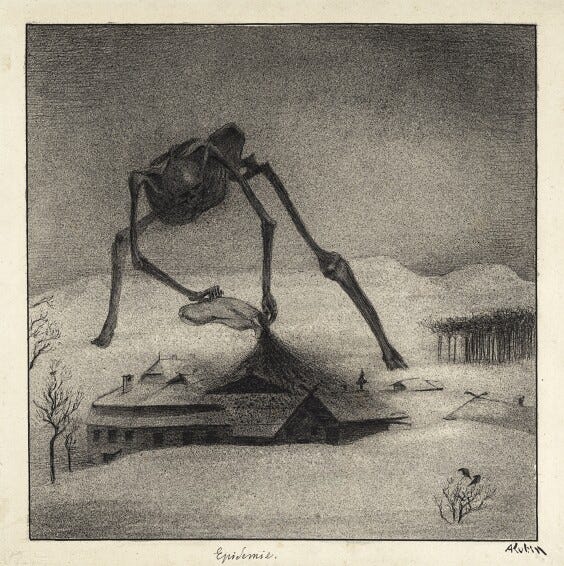

Epidemic (1900/1)

In this scene, death (personified by a giant skeleton) unleashed pestilences upon a a snowbound country village. In this ink drawing is supplemented by ink spray, blown manually by the artist through a common twin-tube arrangement. This provides the speckling effect that gives the scene its gritty appearance. This replicates the appearance of aquatint prints. Kubin’s art was equally strong in stand-alone drawings and prints; it is often not easy to distinguish between the mediums.

A Dream Visits Us Every Night (1900)

In this vision, a giant demon in the form of a skull-headed woman with insectile legs stalks the land at twilight. We get the sense, from the foreground of windblown foliage, that we are low to the ground, luckily hidden from this monstrous creature. It appears hugely dynamic and mobile, capable of reaching a prey in a few gigantic strides. This vantage point and the inclusion of foliage to give scale conveys to us to us how gargantuan this creature is. Kubin’s brilliance is not simply to invent such a monstrous hybrid but to include a moody dramatic landscape that indicates time of day, weather, location and scale with sparing brevity.

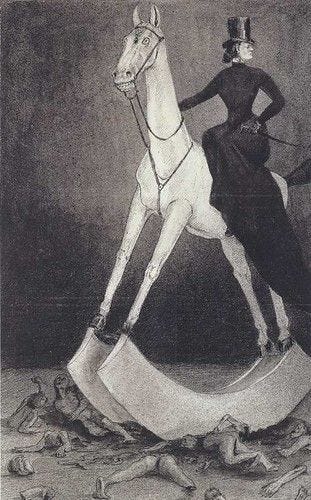

The Lady on the Horse (1900/1)

Kubin was noted for his illustrations, some of which had humorous elements. While this image is closer to horror than humour, the scene is as much satirical and bizarre as it is gory or shocking. Max Klinger’s series of prints The Glove (1877-8) was an influence on the young Kubin. In some respects, this picture is close to The Glove, with its combination of fantastic elements and satirical observation of everyday life. The juxtaposition of humour, fairy tale and violence is something found in the graphic work of Goya and Paula Rego.

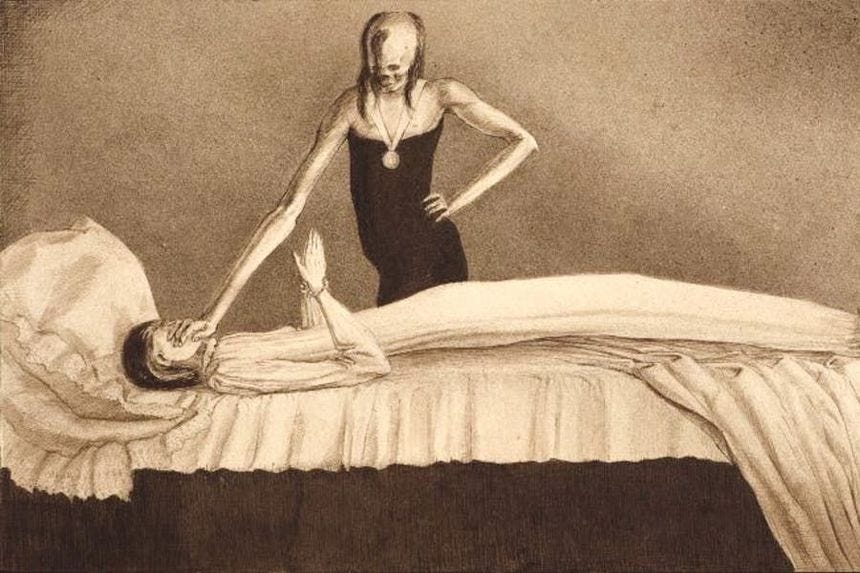

The Best Doctor (1901)

In the final image selected, death takes the form of a skull-headed woman who becomes the ultimate doctor, who ends all suffering and illness by terminating life. She seems to be suffocating as much as closing the subject’s eyes. Is the man really dead? The tense arc of his body and his hands in the position of prayer suggest he is only now dying with the intervention of this supernatural personage. Yet he seems resigned to his fate, regardless of momentary suffering. Death is (of course) unavoidable.