Abstract Romantic

From the Renaissance to Dali, romantic imagery usually means precision. The drawings of Victor Hugo show it doesn't have to be so

Often, when we think of Romanticism, we think of a liberated imagination but a very constricted veristic technique. Even the mistiness of the mountains of Friedrich are precise in their softness and ambiguity – it is distilled and calculated. The arid plains of Dalí’s Ampurda and the gently graded skies above have the same exactitude. In the Nineteenth Century art we discern a broad consensus on technique, namely that clarity aids the imagination. Description of the unworldly demands the artist put in sufficient work and persuasive description to allow us to grasp the meaning of his unexpected proposition. In the minority are those Romantic artists who follow the loose technique of Turner, whose imagination is to do with space, light and colour rather than the precisely depicted phantasmagoric. One exception is Moreau, who moved between detailed description of the astonishing motif and a loosely implied setting of grandiose or exotic character.

Another exception is the writer-author Victor Hugo (1802-1885), whose drawings can be seen in Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, Royal Academy, London 21 March-29 June 2025, a display now entering its closing week. Hugo was a gifted draughtsman – an architectural drawing made in Belgium shows Hugo had terrific powers of observation – but his vivid imagination was the type that can interpret natural forms in fantastical ways. The grain of wood is a flowing river, a stone is a skull, a cloud is a floating fortress. In this exhibition of his ink drawings, which involve daring technique that matches the vivid imagination, we find an artist of the highest level opening his imaginative faculties in a manner few others have ever harnessed to such effect.

Aside from the adolescent activity of caricature, Hugo’s initial impetus to draw seems to have been the desire to record and transmit to correspondents what he saw abroad. He also developed fantasies, such as invented buildings, to amuse himself and others. These thoughts were part of a retreat from modern life, as (on the whole) Hugo’s real and invented scenes omit signs of contemporary life. In that sense he has the temperament of a reactionary, although his politics were to become radically liberal and progressive.

Although we might consider Hugo an amateur artist – perhaps even an outsider artist – he was considerable artist. He was an draughtsman of distinction. He was not only technically able, he was inventive and imaginative. This allowed him to take advantage of the accident, harnessing it and allowing it to become a potent expression of his aesthetic vision, conjuring castles from his daydreams on to the page. However, it would be a stretch calling the artistically untrained Hugo an outsider, given his prominent social rank, fame, riches and public acceptance – albeit aligned to the liberals, a political minority during the reign of Napoleon III.

Hugo’s political commitment is explicit in Ecce lex (1854) was drawn to protest the execution of murderer John Tapner is the weakest piece on display. It is a generic scene of a hanged man – so generic in fact that it was reused with a new title John Brown, to campaign for the cause of the convicted abolitionist sentenced to death in the USA. Repeal of capital punishment was one of the liberal causes Hugo advocated in favour of. His attempts to save Tapner and Brown failed but eventually his liberal cause prevailed. This was also the case for Hugo’s support for the campaign to abolish slavery, which Hugo claimed was a justification for treason.

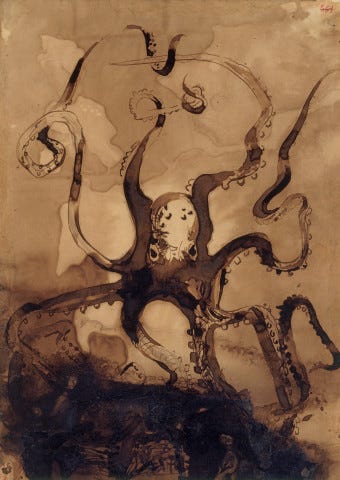

The exhibition has an unfinished drawing of a harbour (from a 1843 sketchbook), which includes pencil guidelines drawn in advance of the ink lines that were applied over them. Others reveal the same approach. With other drawings, something more spontaneous and less structured seems to have been the approach. Hugo flexibility is one of his best qualities as an artist. Hugo sometimes worked by wetting a sheet of paper then applying ink in washes that bloomed and rippled. He would also scrub ink with a rag, making marks that were organic, unpredictable and uncontrollable. They are often very sophisticated in terms of manipulating the chance effects of ink wash on paper and also making deliberate designs look organic. Bunched brush bristles create of wavy parallel lines of swelling sea and falling rain.

If one were to make the case for Hugo as a fantasy artist[ii], a choice example would be Les Orientales (c. 1855-6) which has an exotic castle in silhouette under a gloomy sky.[iii] The touches of intricate gemlike colour heighten the gothic atmosphere. It is just like a depiction of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast and would serve as a good cover illustration for that book, if Peake had not already got in ahead with his own drawings. Hugo’s inconsistent political outlook – more personal and emotional than ideological in basis – included an opposition to Haussmann’s programme of modernisation of Paris, which destroyed much of the remnants of the Medieval city. On this topic, Hugo’s aristocratic sentiment and Romantic taste overrode his populism.

While Hugo spent more time drawing than writing fiction in the late 1840s, so the materials he deployed became more diverse, coming to include not just ink but watercolour, charcoal, pencil, wax and lithographic crayon. He started to use stencils to mask areas and started to collaborate with printmakers who could reproduce his compositions. The late The Castle with the Cross (1875) is a great translation of Hugo wash technique as a large (75.9 x 132.2 cm) multi-plate etching.

The gallery has glass cases holding sketchbooks and letters, also pebbles Hugo retrieved during walks and upon which he inscribed dates and places of their finding. Photographs of his Guernsey home Hauteville show how thoughtfully the author-artist curated his living space, turning it into a Gesamtkunstwerk, made from his sensibilities in order to stimulate his creative work. Hauteville – a town house in St Peter Port – is preserved to this day as a house-museum. The richly patterned furnishings have a beguiling hypnotising effect. The glazed look-out allowed Hugo to gaze directly across the sea while writing and drawing in comfort. The sea was a constant subject during his time in exile at Hauteville on Guernsey (1855-70) as well as the preceding years on Jersey (1852-5). The watery effects of ink wash suggested waves in heavy weather, ships at sea, shipwrecks and sea creatures.

Hugo did much of his drawing during a period of grief that lasted about a decade, following the death of his daughter in 1843, a period when he did not publish and wrote little. The drawings seem primarily for his own entertainment and edification. Of an estimated 4000 drawings made, 3000 survive, many in the archive collection Maisons de Victor Hugo, based in Paris and Guernsey. Although the drawings were not exhibited publicly, they were seen by associates of the artist. Colleagues saw and were appreciative of Hugo’s drawings, with Baudelaire and Delacroix speaking warmly of them.[iv] Hugo did drawing in copies of his books which he gave to friends. There is a really accomplished and beautiful drawing (1867) of a flying bird approaching its nest, painted on the flyleaf of Les Chansons (1866). A few pictures were made for newspaper publication. It seems Hugo toyed with the idea of including his drawings as illustrations in his books but that did not come to pass until late in his lifetime.

Hugo has received particular attention over the last 80 years because he is seen as a precursor of Surrealist autonomism and Abstract Expressionism. Not least, this is due to the expressed admiration of members of these movements. Breton and Picasso bought drawings by Hugo and Breton wrote, “Victor Hugo was a precursor of Surrealism in the matter of his technical experiments, which imply a controlled dialogue with chance in order to make evident certain forces which remain hidden from us.”[v] The ambiguous haunting Dead City of c. 1850 precedes Max Ernst’s petrified forests by 80 years but is hardly different in character and freedom.

The Abstract Expressionists adopted Hugo at a more superficial level – in a similar way to how they took up the unfinished watercolour sketches of Turner – finding in his tachisme a formal correlation to de Kooning and Kline’s rough brushwork.

Beyond the technical innovations of Hugo, it is worth weighing up his attachment to spiritualism. Hugo’s liberal rationalist side is in conflict with his intuition that the artist is one of the great men (as defined by Carlyle) and as visionary speaker for his people (as proposed by Nietzsche). Many of Hugo’s champions are progressives who have little feeling for Hugo’s grandiose sense of his spiritual mission for not as an advocate for the masses as an abstract, but as artist in contact with supernatural forces, guided by spirits. Hugo was not a conventional Christian but a latter-day pantheist. Contemporary materialists’ discomfort with both the great-man theory of history and spiritualism has meant Hugo’s political rather than spiritual drive has taken the fore in interpretation. As a recent authoritative compilation of verse puts it: “His conception of the poet’s role as intermediary and interpreter between man and God, man and Nature, man and History, can seem to us the outrageous pretentiousness of an overdeveloped ego.”[vi]

Considering the debate over the rejection of internationalist Post-Modernism and Conceptual art purposed to the globohomo and leftist agendas, Hugo’s art is worth consideration. If we do choose to pay more attention to the Romantic and accord it a place for serious endeavours in making new art and using it to revive national mythology, then for that Romantic art to be living, Hugo’s vigorous improvisatory style is an exciting path that can counter the somewhat leaden self-conscious productions of the Retvrn to Tradition camp. Hugo’s visions of castles, monsters and sea storms give us powerfully atmospheric and dramatic scenes that spark real feeling and demand attention. Their ambiguity requires active engagement from the audience in the form of identification, concentration and reflective consideration. Surely, if we want art to draw out of viewers deep feeling, such mental and imaginative engagement is not only appropriate but necessary. Nothing kills the primordial excitement quicker than picture-book naturalism. Consider Hugo’s risks and the high standards he sets for himself and you. This should be the gold standard of new fantasy and Romantic art.

Astonishing Things: The Drawings of Victor Hugo, Royal Academy, London 21 March-29 June 2025

[i] P. 13, Sarah Lea “Double Vision: Victor Hugo’s Mind’s Eye”

[ii] As is made in William Gaunt, Painters of Fantasy, Phaidon, London, 1974, which was where I first encountered Hugo’s drawings.

[iii] Hugo had published his poem of the same name in 1829.

[iv] Delacroix: “If Hugo had decided to become a painter instead of a writer, he would have outshone the artists of their century,”

[v] Quoted, Stefanie Heraeus, Surrealism and the Visual Arts, Cambridge University Press, 2002

[vi] P. 40, William Rees, The Penguin Book of French Poetry 1820-1850, Penguin, London, 1990