A Sum of Destructions: Why artists dispose of their art

When an artist destroys his own output it is painful, necessary and cathartic, but we shouldn’t fetishise it

Last week I completed and submitted the manuscript of my next book. In it is some advice to artists. I suggest that artists make as much art as possible and destroy as much they can bear to. As with all my advice, it is good – perhaps because I am so bad at following good advice, I struggle to follow my own rules. It is as if all my wisdom and virtue are exhausted by thinking up rules and writing reviews.

While I was in going through my archive, I was thinking of this and what came to mind was that famous phrase that Picasso never said: “Art is the sum of destructions.” “Every act of creation is first an act of destruction” is apparently a pithy epithet derived from an interview with Picasso, but it is only later writers who condensed it further into the semi-koan “the sum of destructions”. Picasso meant that each great artist had to dismantle the conventions that exist in his culture and the rules in his head before you can approach a picture with fresh eyes and an open mind. He could be said, through his Cubist and proto-Cubist innovations, to have destroyed linear perspective and pictorial depth as a convention in Western painting. Bearing in mind the evidence of films of Picasso working out large pictures in the 1950s, we know that some of his own paintings subsumed potentially complete earlier iterations in a sequence of radical revisions that eventually led to the final surviving version. Matisse’s paintings also went through such dramatic rethinking, as captured in photographs.

We can also call every picture an arrested development. It is a considered decision to stop the production process, taking the latest stage as the last, satisfactory within itself.

Creation of pictures is the result of the deliberate destruction and defilement of the virgin picture surface. Some artists have spoken about a creative block they experience in the presence of the snowy perfection of a blank canvas or clean page. There is something formidable about the untouched surface. It is immaculate and unimprovable in its pristine cleanness. It is ideal and has limitless potential. In that sense, surmounting respect and overcoming anxiety in the face of such insolent beauty is a hostile act – where an artist dares to presume that his thoughts and work is superior to perfection, he becomes hubristic, egotistical and (therefore) quintessentially human. He breaks the utter clarity and serenity of the mirror surface of the lake by throwing a stone. He needs ripples; he must make a mark; he must change the world as he finds it. Fear of annihilation, anxiety in the presence of the void, enervating horror vacui, animus in the presence of perfection – all these spur on the artist. They may not be noble or sophisticated motivations but human beings – and especially artists – are not sophisticated. The expressions they produce can be fantastically complex, incredibly refined and filled with meaning and ingenuity but what drives the artist is (essentially) raw, base, simple. Art as defiance and rage is something that we would be wise to acknowledge more.

Anyway, back to my advice. I recommended to artists that they destroy as much of their own output as they could because although we tend to assume that our achievements will be measured on our best, there is no reason for others not to judge us on our worst. So, you may have produced a masterpiece but if all someone knows of your efforts is a poor picture, they will rightfully have a low opinion of you. Every picture is a proclamation of your abilities and intentions. It bespeaks of your assessment of yourself and your audience, ultimately acting as a measure of your seriousness. So, you have a duty to yourself and your audience to remove the weakest of your pieces. Ironically, Picasso was notorious for keeping virtually everything he produced, selling only reluctantly. Happy to destroy pictures as an evolving work in progress, Picasso never seemed to have any doubts, regrets or second thoughts once he had settled on the final version – no matter how pedestrian or silly his weakest pictures were (mainly post-1945).

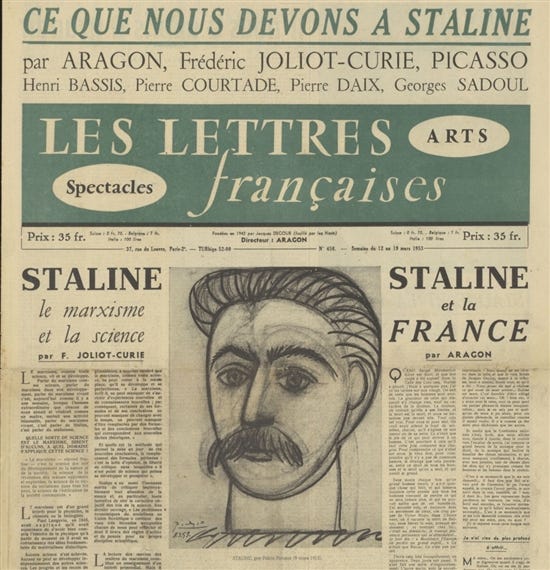

Yet there is a famous missing picture. His 1953 commemorative drawing of Stalin was lambasted, mainly by the Left, as being insufficiently heroic or dignified, has disappeared. Post-publication, the drawing was not exhibited and was probably destroyed by Picasso – a rare manifestation of regret. We can dismiss his later criticism of his own Blue Period as being too maudlin and too popular as being a tactical disavowal when he wanted to depict himself as a cutting edge adventurous formalist rather than a holdover of sentimental Post-Impressionism. He held on to a few Blue Period paintings and never bought back anything of this period, when he could have afforded to buy and then destroy the art he claimed to disdain.

As Picasso – that inveterate hoarder – knew that being ruthless is necessary. His ruthlessness came in the pillaging his private life for subjects and driving hard bargains with dealers and collectors. Quite early in his career, he had unlimited storage for anything he wished to preserve so that he could afford to be indulgent, knowing that everything that came from his hand had a ready audience (albeit only historians, fans and collectors for his most inconsequential doodles). His destructive tendencies were saved for sacred cows and his lovers.

Viennese Expressionist Richard Gerstl was so distraught at a failed love affair that he destroyed almost everything he could get his hands on, which – sadly for us – was almost everything he had made. Having disposed of his art, he disposed of himself.

Francis Bacon destroyed his pictures freely and is generally considered a more consistent artist than Picasso (qualitatively speaking) because of his high level of quality control. As I have commented elsewhere – and it is not an observation unique to me – that Vermeer seems so close to perfection because his surviving output is a mere 35 paintings, no drawings, no prints. It seems unlikely Vermeer destroyed much; he simply painted very slowly and sparingly, with a handful of paintings being lost over the centuries. Vermeer is the inverse of what I recommend: paint little, destroy little.

Some artists have fetishised destruction. In 1970 John Baldessari burned early pictures and preserved the ashes, which he later exhibited. In May 2008 Michael Landy inventoried his possessions, including old art works by himself, before publicly destroying it. I remember student artists enacting other such performative renunciations. It was a purging, a renewal and statement intended to impress onlookers. I destroyed hundreds of adolescent drawings, but I did it in private. The sheets seemed apprentice work, technical exercises to be cleaned away.

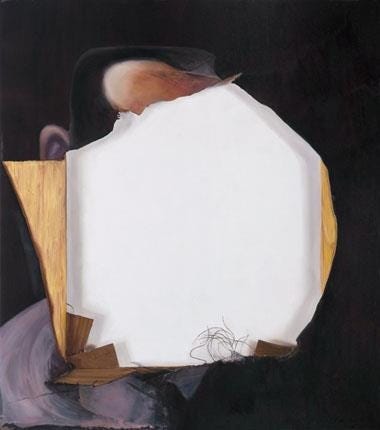

This week I took up my own good advice – that is, every time you visit the storage unit, remove a box of material and cut up a mediocre painting – and I destroyed a painting. That particular painting I had had in mind for years. It had been painted in December 1999 and had been exhibited once. I paint from three sources – life, imagination, found/taken photographs – with further pieces formed using hybrid approaches. This one had been derived from a photograph found in a newspaper. It showed a child walking in a trainyard. It was supposed to convey the fragility of childhood and the difficulties of a youngster coming to terms with life in a complicated and unforgiving world, mechanised and regularised beyond their comprehension or power to alter. What made it effective as a photograph made it null as a painting subject, I soon discerned after making it. There was nothing I could bring to the painting that was not present in the photograph. Artistic or highly staged photographs are too finished and theatrical to be good sources for painting as they lack the gaps, the rough edges, the rawness, the ambiguity that makes for a fertile source. These artistic shortcomings are where the imagination and the trial of making intervene and inject magic into the resultant art.

The reason I kept this canvas – and was weak enough to exhibit it once, many years ago – was that it was a fine piece of technical painting. But technical painting is for connoisseurs and other painters to appreciate and is never enough to carry a clichéd image or a banal message. (Banal here does not mean untrue, simply uninformative.) If firemen managed to rescue from my storage unit on fire this painting alone, the index of my overall achievements would be lowered. I would be ashamed. So, preserving something which was little more than a technical exercise and artistically unambitious was a liability. Moreover, a reluctance to dispose of the inadequate chained me to weakness when I needed to be strong. Why hold on to something third rate when you expect to achieve greater heights? In that respect, purging the past and disposing of the shoddy was incumbent upon me as a maker and a man.

I did not feel anything as I cut the painting up and pulled the scraps from the stretcher. There was neither relief nor regret. I knew I had done my the good paintings the service of stripping away an unworthy one. I had cut back the diseased tree so that nearby trees could flourish and be seen.

Not everything an artist makes can be of the highest quality and I do not advocate that artists should destroy right to the bleeding edge of exceptionality. Sometimes a picture has sentimental value or is of a notable subject; a picture can be made as a commission that falls short of originality; middling pictures might need to be sold for money; a picture might a career landmark. All of these pictures are worth preserving – but do not get into the habit of saving pictures for the sake of it. Get into the mindset that a picture has to earn its keep.

Keeping a canvas is pristine condition for a quarter of a century when it is not work you are proud of nor a picture which you could in good conscience sell is not an achievement. It is a failure of nerve and an error in judgment. Be brave when you make and when you destroy. Only by being brave will you allow your other qualities to emerge into the sunlight and plain view.

There is another reason to destroy work - too bloody much. By a strange coincidence the day before I read this I went through all my art school life drawings of the 1980’s and ‘90’s and decided that only one in five would be spared, those that show some spark of life while tearing up the routine and failed. But the main reason is I’m getting old. I don’t want to give my son the sad task of sorting through my work when I am gone. I am trying to make it easier for him. Figure work is no longer a main part of my output, these belong to my past. Let them go.

Giacometti was also known for frequently destroying his works.